Over the past 50 years, more than a third of bird species in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ have faced declines, a new federal study has found.

Published Tuesday by Birds ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and the federal government, the is the most complete federal tally documenting the disappearance of bird species to date. Since the 1970s, it found 168 bird species (36 per cent of those surveyed) have seen their populations deteriorate.

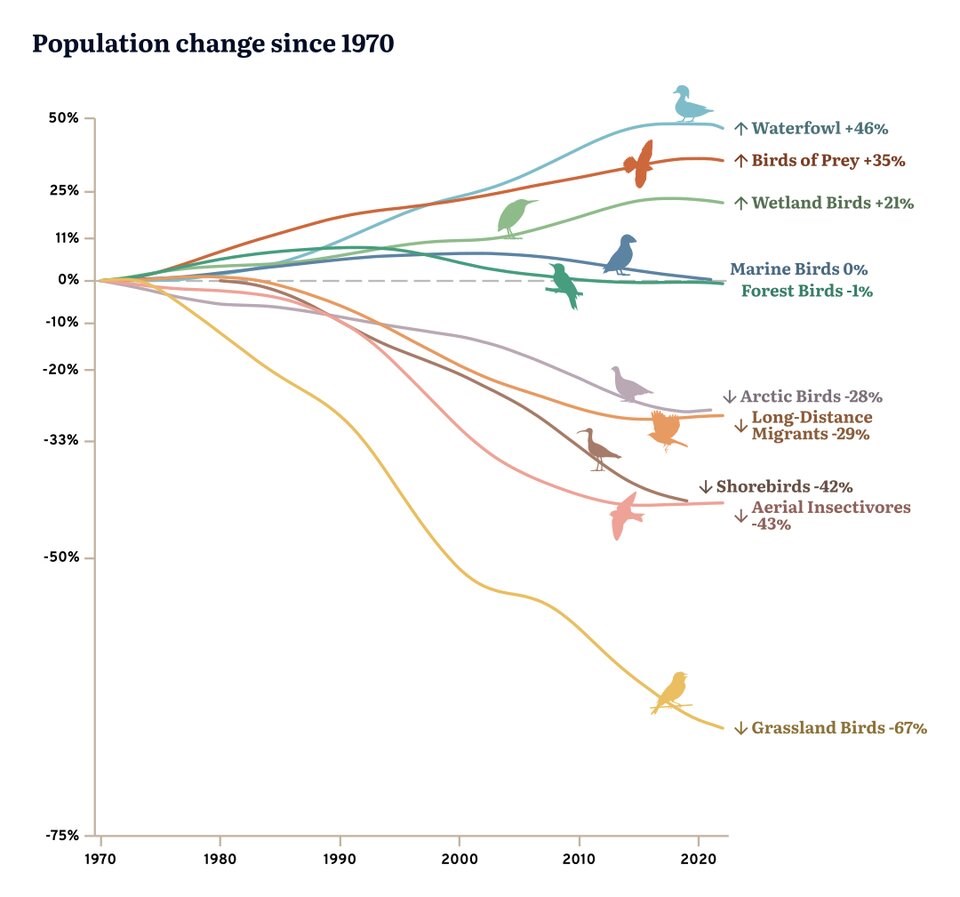

The steepest declines were found in grassland birds, where 67 per cent of species saw negative changes.

“We’re really seeing this crisis in the Prairies,” said Catherine Jardine, Birds ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s project lead on the report.

Last published in 2019, researchers have improved data on a number of species, allowing them for the first time to include a number of new birds, including owls.

There is also now enough data to group birds into long-distance migrants and Arctic birds, who alongside shorebirds and aerial insectivores, all saw declines ranging from 43 per cent to 28 per cent.​

​Marine birds showing early signs of decline

Many shorebirds documented in the report came from ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s coastal waterbird survey, which captures the health of many Arctic and boreal birds as they migrate south for the winter.

“Comprehensive shorebird data in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ only dates back to 1980, but in that time, there has been an alarming decline of over 42%,” the study notes.

The province’s seabirds, meanwhile, followed a fairly level trend until numbers started to dip down in recent years. Scientists think that’s a result of a combination of habitat destruction, a rise in severe frequent winter storms, ocean plastics, and invasive species.

“That's reflective of the trends globally for marine birds,” Jardine said. “Marine birds are, globally, potentially one of the most imperilled groups of species.”

Climate change remains a “significant and growing threat to birds in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½” partly due to an increase in storms, floods, droughts and wildfire. And plastics, pesticides and other contaminants from agriculture and industry affect birds in all habitats, the report says.

​Conservation measures appear to work, says expert

While some populations remain below their 1970s levels, there are signs of a rebound. Aerial insectivores like swifts and swallows were in sharp decline but are now levelling off and even increasing in some cases, something Jardine attributes to conservation measures.

Those gains come on the back of a number of waterfowl, birds of prey and wetland birds, whose populations have buoyed in recent decades after a brush with extinction, according to the report.

“We tend to focus on the groups that are in decline. But we’ve also seen huge increases,” Jardine said.

The data analyzed in the report is based off of targeted surveys and long-term monitoring by tens of thousands of citizen science volunteers.

Jardine said the fact that birds live alongside us, in our backyards and along our shorelines, means the public can act to influence the future of birds.

The report calls on the public and conservation officials to take a number of actions to mitigate the decline of several bird species — from improving bird habitat and using less fossil fuels to keeping cats indoors.

Outdoor , meanwhile, are estimated to kill more than 100 million birds in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ every year, while kill another 25 million birds.

“For me, birds are indicators. They are telling us what we know,” she said.

“We know when we put in effort, conservation works.”