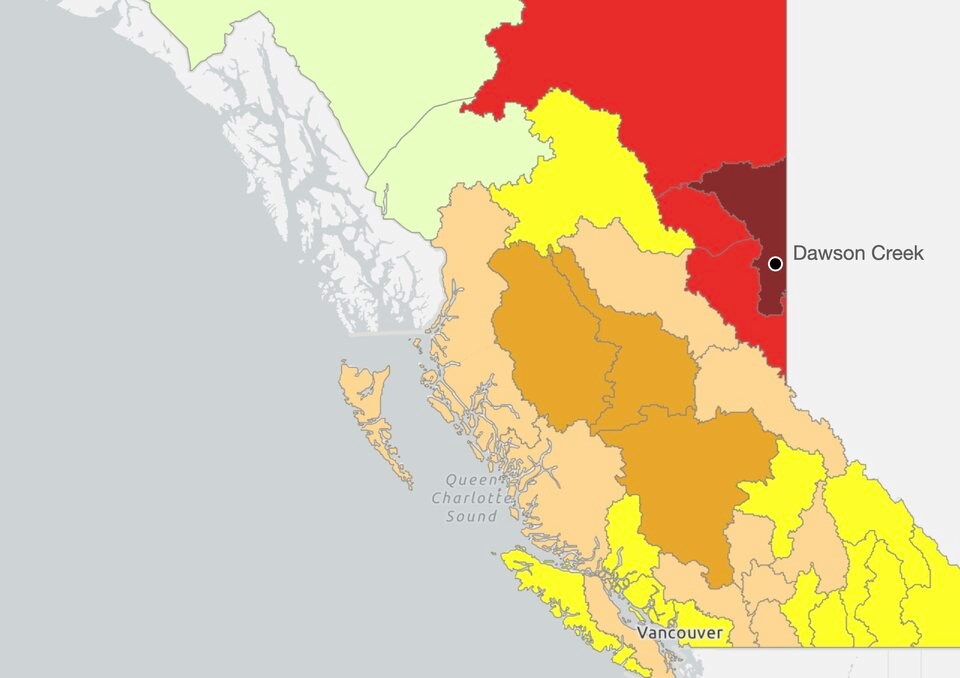

A corner of northeast British Columbia representing nearly a fifth of the province has reached high to extreme drought levels, a water shortage so dire it ranks among the worst drought conditions in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

Dave Campbell, head of the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ River Forecast Centre, said the latest drought data shows a wide swath of land in the Peace and Fort Nelson districts are facing multi-year drought conditions. In Fort St. John and Dawson Creek, the region’s rivers have experienced nearly two years of record low flows — conditions that impact both local people and wildlife.

“It's not just that it's dry. It’s really unprecedented in terms of the climate records that we have going back 100 years,” Campbell said.

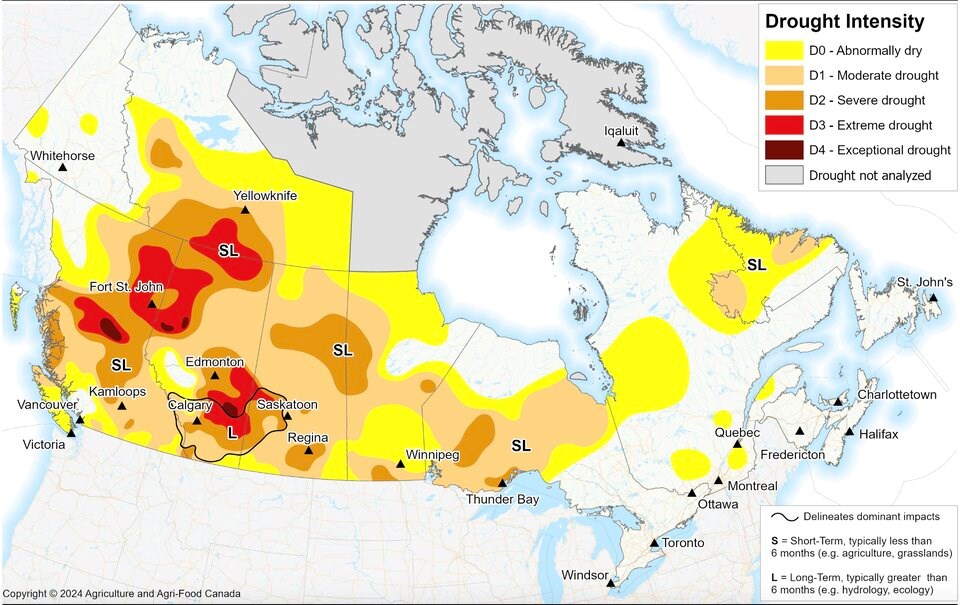

Trevor Hadwen, an agro-climate specialist with Agriculture ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, said most of Western ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ has been in drier than normal conditions for over four years.

In the last month, large parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba have seen a big improvement. The same is true for Vancouver Island, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s south coast and in the Okanagan, where a slight dip in temperatures and increased rainfall have eased drought conditions and slowed the melt of already record-low snowpacks, Campbell added.

But in a swath of land extending from northeast ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, the Peace River region of Alberta and the Northwest Territories as far as Yellowknife, Hadwen said conditions remain the most dire in the country.

“We’re talking about a drought that has a return period of about 50 years,” Hadwen said, and “likely more.”

The drought conditions and low snowpack continue to put pressure on the province's hydroelectric reservoirs.

BC Hydro spokesperson Kyle Donaldson said in an email that drought in 2023 resulted in below average water levels at the utility's largest reservoirs. Because of that “historic drought,” Donaldson said BC Hydro imported 11,000 gigawatt hours of electricity from outside of the province.

“While it is still too early to forecast how reservoir conditions across the province may change over the spring and summer, because of the near record-low snowpack this year, we anticipate similar challenges for managing reservoir levels and discharges, this summer, similar to last year,” he said.

Water deficit puts pressure on ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ farmers

Some of the first to face the impacts of drought have been farmers. About 20 kilometres west of Dawson Creek, Chris Moat spent much of Thursday seeding his 1,500-acre, family-fun farm, where he grows a mix of crops — from wheat, barley and oats to canola, flax and peas.

The farm land is not irrigated, meaning it relies on water from snowfall and rain that falls throughout the year. Moat said drought conditions carried over from 2023 were made worse by a lack of winter snowfall. By May 15, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ snowpack data showed the province was at 57 per cent of normal levels.

“We’re already starting at a deficit for water,” said Moat.

Moat said some rain has fallen in the past week, but not enough to remove fears some farmers have of a deepening drought and the lack of hay that comes with it.

A few kilometres away, cattle farmer Joyce Studley, 81, figures she has fed hay to her 380 cows 200 days this winter. Two weeks ago, they ran out and have been scrounging to feed the animals ever since.

“I’ve used all the resources I had since May 15 — begged, borrowed and stole,” she said.

Studley’s experience is not unique, with drought leading to cattle feed shortages across ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ since 2021, according to Agriculture ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

By June 1, Studley can usually stop paying for expensive bails of hay. That’s when the nearby community pasture is slated to open. But this year, a lack of moisture means its opening has been delayed at least a week.

“They have to leave enough grass for deer and moose. It’s only fair. They would suffer,” Studley said. “But there’s just no rain to get it started.”

“What do I tell 350 cows and their calves? Don’t eat for a week?”

‘May lose the whole bloody place’

Water for cattle has also been scarce. One of two watering holes dug to accumulate water on her farm has run dry. Studley says they’ve resorted to siphoning water from the other. And without a “damn good rain,” she said the farm will soon run out of water for the cows to drink.

“It’s pretty dire right now,” she said. “We are in trouble.”

The pressures growing on Studley and her 84-year-old husband have been in the making for years. She said about a decade ago, they spent $80,000 (their life-savings) on hay, thinking a government program to reimburse farmers would pay them back. The government reimbursement cheque came back at $2.58, the farmer said.

Studley said she has struggled to trust government programs ever since, describing them as “a lot of hot air.” The couple carried on, working jobs as store clerks and school janitors to try and get the farm on its feet.

“We’d farm until about 2 p.m., work until midnight and get up at 7 a.m. to get the kids to school,” she said. “Did it for 40 years. We did this because we had the dream of the farm. We’ve got the dream now. Then this drought.”

Because of their age and inability to feed the cows, the couple is now considering selling them off. No sense in saving even 30 cows when you don’t have the time to rebuild the herd, figures Studley.

“We may lose the whole bloody place, but we won’t be the only ones,” she said.

Some remain positive amid drought, but fears of fire remain

Moat said he’s slightly more optimistic than many of the cattle farmers around him. While drier than it should be for this time of year, he’s holding out hope that June rains will bring needed relief.

“I guess we’re forever optimistic. That’s why we farm,” he said. “We don’t have any options. If we don’t get it, we don’t get it.”

On the other side of drought, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s northeast has been a major hot spot for wildfires over the past 18 months. About 160 kilometres to the north, holdover fires from the 2023 Donnie Creek wildfire — the largest the province has ever recorded — continue to burn, according to the BC Wildfire Service.

This year, wildfires have already prompted the evacuation of nearly 5,000 people across the province’s northeast, and both Moat and Studley say the skies over their farms have turned smoky a number of times.

“Across from me, it’s pure bush. We’ve had a couple of fires we’ve had to put out,” said Studley. “We can’t keep ignoring this climate change.”

“It seems just a matter of time before it burns us out.”