The heavy demand for a small square piece of tin foil is evident as drug users pass through the gate of an open-air consumption site in the Downtown Eastside.

The man handing out the diminishing supply is D’Arcy Knape.

“Tin foil is our number one request — by far,” said Knape, working behind a table of smoking and injecting supplies Wednesday at the Overdose Prevention Society’s site at 99 West Pender St.

Drug users need the foil to heat up their drug of choice.

Once the drug melts, the user inhales vapours through a small tube or straw to get high.

Unlike needle use, the method leaves no tracks on a person’s arm and various medical journals have suggested smoking reduces the risk of contracting infectious diseases such as Hepatitis or HIV, which are commonly associated with injection drug use.

Even so, smoking drugs is deadly.

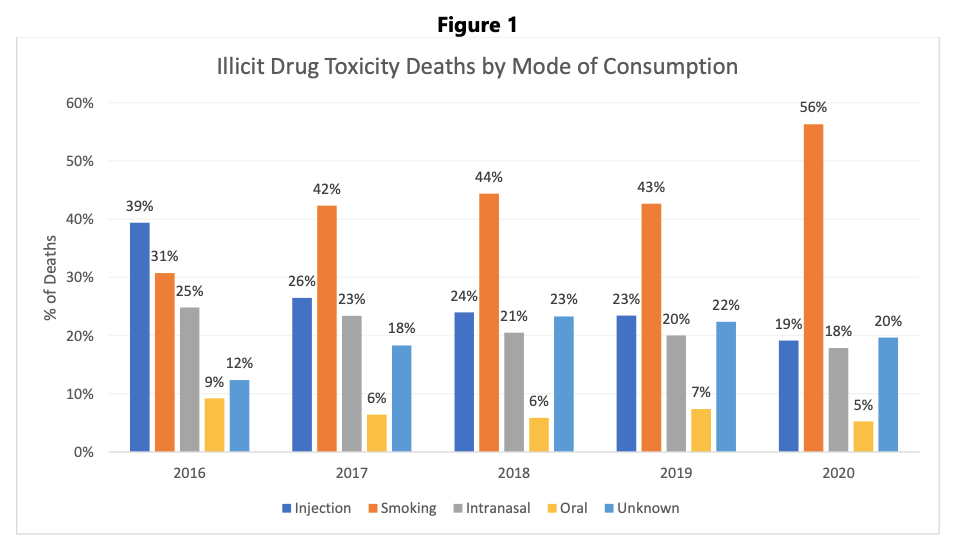

Data released last week by the BC Coroners Service shows the highest percentage of overdose deaths in the province from 2017 to 2020 was the result of smoking rather than injecting drugs.

In 2020, for example, 56 per cent of deaths were attributed to smoking and 19 per cent to injection drug use. Intranasal consumption, or snorting, accounted for 18 per cent of deaths while oral ingestion was connected to five per cent.

Evidence of multiple modes of consumption were found in 16 per cent of cases.

The percentages, however, could be higher or lower in one or more of the categories because the coroners service was unable to conclusively say in 20 per cent of the cases which method of use led to a person’s death.

What’s clear though is there was a shift from 2016 — when injection drug use at 39 per cent was the number one mode of consumption linked to deaths — to 2017 when smoking became the leading mode at 42 per cent.

That trend continued in 2018, 2019 and into 2020, with the coroners service yet to release data on how the 2,224 people who died in 2021 consumed their drugs, although longtime drug user Matt Savage suspects smoking will still be the predominant mode.

Sitting at a picnic table at the consumption site Wednesday, Savage pointed out that only one of about a dozen people were injecting their drugs, while all others were smoking, either by using the tin foil method or by pipe.

Savage, 48, was a 25-year injection drug user until he switched recently to smoking.

“My veins just got shot and I couldn’t hit myself [with a needle] anymore,” he said, noting the damage various cutting agents in heroin and fentanyl did to his veins. “When my veins started going, I just got tired of searching for hours to find one vein and ruining a whole bunch of dope at the same time.”

The context Savage provided to the coroners service data was that smoking hasn’t suddenly become more dangerous than injection, but that there are simply more people choosing to consume drugs by smoking.

Young people, too, he believes prefer smoking over needle use, an observation shared by Knape, who works with Savage as a peer support worker at the site.

Young people, Knape said, don’t want to stick needles in their arms.

“Some do, of course, and I'm just generalizing, but it's messy,” he said. “The foil delivers what they're looking for — it delivers the high, the low, the whatever just as well as needles without having to tie off [an arm with a band] and have the stigma associated with it. That's my take anyways.”

'No heroin around'

Heroin has been Savage’s drug of choice but he now searches out fentanyl.

“That’s all there is on the street now — there is no heroin around,” he said, noting he quickly developed a tolerance for the synthetic opioid, which has been linked to more than 80 per cent of overdose deaths in 乌鸦传媒 for several years.

He doesn’t consume as much as he used to, having recently become a client at the nearby , where he injects prescription heroin, or diacetylmorphine. The injections, however, are done intramuscular, which allows the medication to be absorbed into the bloodstream.

“There are times during the day when I do feel a little bit edgy, and then if I smoke a little bit, then I'm fine,” said Savage, noting his consumption of fentanyl decreased from a quarter ounce a day to a half gram. “So if that's all I'm doing, I'm happy with that.”

He said his experience, so far, is that a safe supply of a drug can reduce his dependence on street drugs. More consumption sites with inhalation rooms would help, he added, but users being able to access medical grade alternatives to heroin and fentanyl are key to reducing the harm.

“Like a smokable version of fentanyl,” he said. “I don't see why the government couldn't do that and give us a product to use that doesn’t have all this crap in it that’s on the street — that’s not going to have disease in it, not going to have bugs in it, not going to have, you know, fecal matter in it.”

While the debate over safe supply continues, Sarah Blyth of the Overdose Prevention Society wants to see more inhalation sites in Vancouver. Limiting sites to injection-only does not serve a population of drug users who prefer to smoke, Blyth said.

“You’ve got to give people every option if they want to use in a safe place,” she said.

As of December 2021, there were 39 overdose prevention and supervised consumption services in 乌鸦传媒, including 13 sites offering inhalation space, according to an email from the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

More consumption sites are in development across the province, including another one in Vancouver, but the ministry didn’t say how many will include inhalation space, or be located indoors versus outdoors.

The ministry noted last year’s budget totalled $500 million for mental health and substance use over the next three years. That sum included $45 million “to ensure the stability of overdose prevention services across the province, support integrated interdisciplinary outreach teams, and increase nursing care.”

Blyth said inhalation sites, such as the one on West Pender Street, could serve as centres for safe supply. She noted the medication and expertise is available in the city to make that happen, but governments have been reluctant to proceed.

“Everyone knows that's what you have to do,” she said, noting several hundred people per day access the site. “We need to get something cleaner than what people are getting on the street right now.”

The economic sense of the argument is that many people who don’t die of an overdose end up in comas, in a vegetative state or in long-term care, said Blyth, pointing out the expensive health costs associated with the crisis.

Vancouver saw 524 deaths in 2021; there were 65 recorded in 2012.

No deaths at drug consumption sites

The coroners service’s report on the 2,224 deaths in 乌鸦传媒 last year points out that no one died at a supervised consumption or drug overdose prevention site. Also, “there is no indication that prescribed safe supply is contributing to illicit drug deaths,” the report said.

Fentanyl, as it has been for several years, was the leading killer across the province.

A review of completed cases from 2018 to 2021 found the top four detected drugs relevant to overdose deaths were fentanyl (87 per cent), cocaine (48 per cent), methamphetamine/amphetamine (40 per cent) and other opioids (29 per cent).

Back at the supply tent, Knape hands a few squares of tin foil to another person who comes through the gate.

The 56-year-old drug user, who also recently shifted to smoking, said foil is also in demand at another one of the Overdose Prevention Society’s sites he works at near the vending market on East Hastings.

He understands the allure to smoking, having seen first-hand the damage injection drug use can do to a person’s veins.

“I couldn't find a vein, it’s inconvenient, there’s blood and when you flag it, which is to draw the needle back to see if you've hit a vein, it produces subcutaneous lumps, which can turn into infections and festers,” he said. “That happened to me one day, and I just said, ‘The hell with that, I've had enough.’”