The first transfer of juvenile Atlantic salmon has been made to Grieg Seafood ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Ltd.’s Gold River Hatchery Expansion Project, which was completed this spring.

Grieg Seafood ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is part of the Norwegian multinational Grieg Group and operates 22 fish farms in the province. One of the largest salmon-farming companies in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, Grieg is aiming to harvest 22,000 metric tonnes of fish in 2022.

The new facility will nearly double the smolt capacity at Grieg’s hatchery and the advanced technology will allow the company to explore retaining fish in the hatchery for longer.

Ultimately, that would reduce the amount of time the fish spend in the ocean, said Rocky Boschman, managing director for Grieg Seafood ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Ltd.

Smolts, young salmon that have reached a development stage in which they would typically be ready to migrate to the sea for the first time, are normally transferred from the hatchery into the ocean when they weigh 100 grams, according to Grieg.

The goal is to let them grow to a kilogram before they’re transferred into the ocean, reducing their time spent in the sea by up to one year, which minimizes their interactions with wild populations, said Scott Peterson, freshwater director for Grieg Seafood ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Ltd.

The larger smolts are also better able to adapt to ocean conditions, have less mortality and show higher resistance to naturally occurring pathogens and parasites in the ocean, Peterson said.

Amy Jonsson, Grieg Seafood ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s communications director, said the company has not yet started growing salmon past the smolt size in the new facility.

“We are looking at potential post-smolt production, as well as increased use of our semi-closed containment systems, both of which will help to reduce interactions with wild populations.”

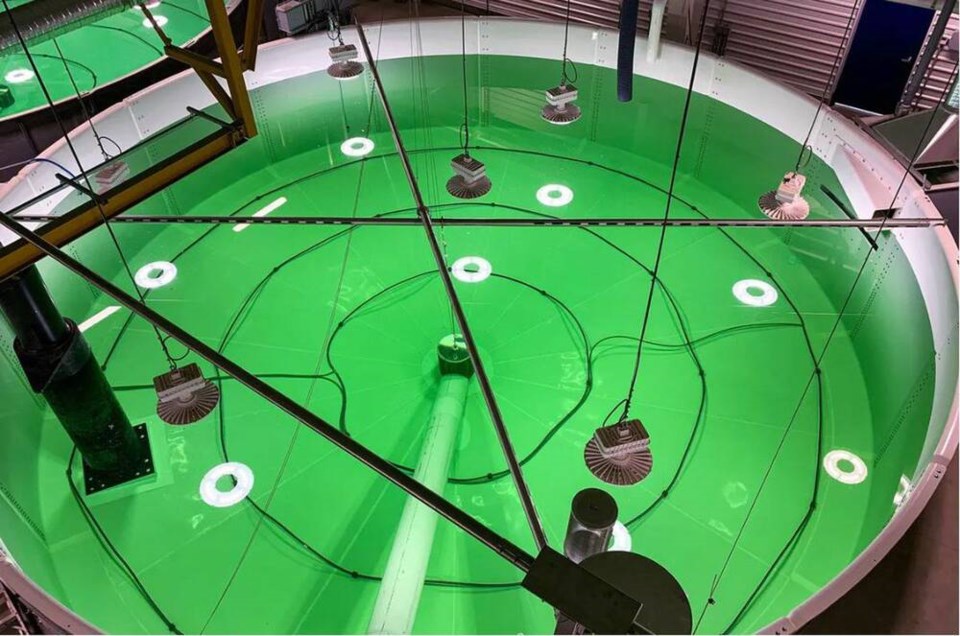

The recirculating aquaculture system reuses over 98 per cent of the water in the facility, said Jonsson.

The new facility has six large tanks that can each hold 326,000 litres of water, providing the capacity for larger smolt sizes as their oxygen, feed and space requirements grow.

“We can only enter as many fish into the ocean as we have capacity [for] though our licenses,” said Jonsson. “But the expansion will allow us to reduce our dependency to purchase smolts from external suppliers, giving us more in-house smolt capacity to meet our overall production goals.”

The ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Salmon Farmers Association called the expansion an “excellent example of the technological advancements the sector is investing in.”

“These types of innovations will be key in transition discussions with all levels of government, including First Nations whose territories we operate in to develop a responsible transition plan for the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ salmon farming sector,” the association wrote in an email.

On June 22, Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray announced the next steps to transition away from open-net pen salmon farming in British Columbia. The government said it would share a draft framework for the transition in the coming weeks, and that a final plan is expected by spring 2023.

Murray has been mandated to pull open-net pen salmon farms out of coastal ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ waters by 2025.

“Wild Pacific salmon are an iconic keystone species in British Columbia that are facing historic threats,” Murray said in a statement. “Our government is taking action to protect and return wild salmon to abundance and ensure ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is a global leader in sustainable aquaculture … we recognize the urgent need for ecologically sustainable aquaculture technology, and we are prepared to work with all partners in a way that is transparent and provides stability in this transition.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Indian Chiefs, has said the “vast majority” of First Nations in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ oppose open-net-pen fish farming due to its detrimental effects on wild salmon.

“Water is contaminated, poisoning salmon, shellfish, and other marine life,” he wrote in a statement. “Such risks are completely unacceptable when wild salmon form a critical food source for approximately 90 per cent of First Nations across ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½”

Grieg’s three-year hatchery-expansion project adds 400 metric tonnes to the original facility’s capacity to produce 500 metric tonnes of fish.

“As we become more comfortable with the technology, we will look to incorporate additional size trials into our production schedule,” said Peterson. “This is part of our overall company goal of transitioning more of our production onto land.”