A ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ border region rich in gold is the epicentre of an investment scheme that costs Canadian taxpayers more than $500 million a year, a new report claims.

The investigation, published by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) — a Washington, D.C.-based group that focuses on environmental crimes and exploitation — targets roughly 20 of the largest prospect mining companies operating in the Golden Triangle, a mountainous region on the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½-Alaska border.

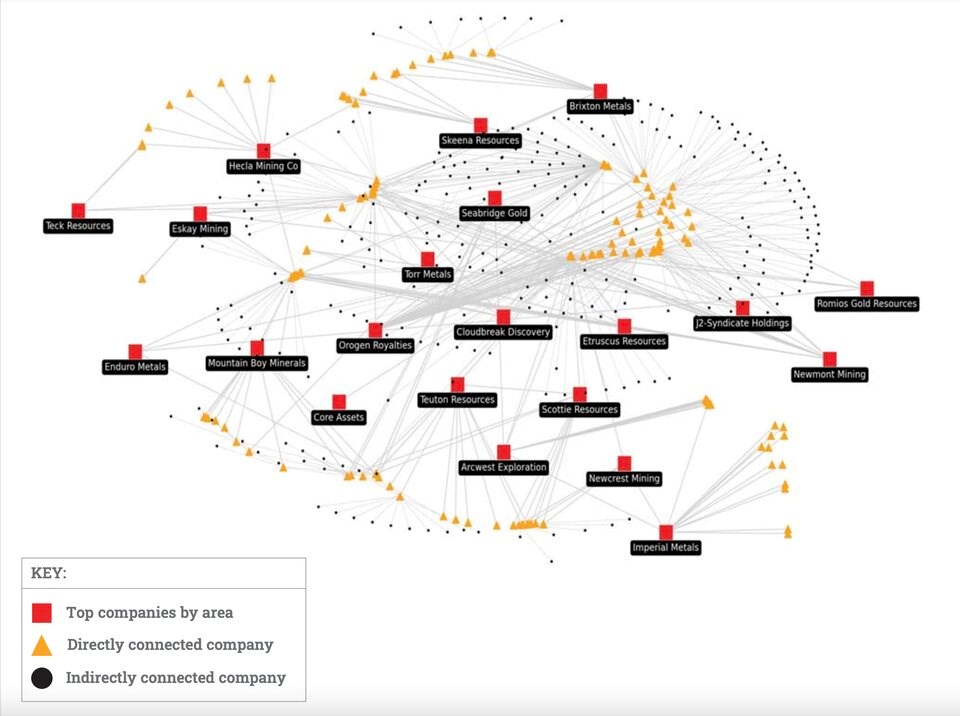

After analyzing five years of public financial documents, EIA analysts traced links to more than 400 other mining companies through joint ventures, partnerships or royalty agreements.

The report claims the companies use tax incentives to leverage big investments while forgoing in a system that has the “structural and operational attributes of a Ponzi scheme.”

With roots in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, the so-called prospect generator companies use investor money to carry out early-stage mineral exploration. By entering into joint ventures, they claim to reduce risk in an industry where conventional wisdom suggests less than one in 10,000 mineral deposits leads to a mine.

The EIA says it has uncovered company behaviour that suggests the prospect generator model is designed to provide tax benefits to rich investors and pay out executives for years on end without generating any revenue.

CT Harry, a senior marine campaigner with the EIA, said he hopes the study will help in “pulling back the curtain” to show the intentional complexity of a business model “designed to obfuscate.”

“It’s a spiderweb of complexity designed to cloak what’s really going on, which is basically, none of these things turn into an actual mine,” Harry said. “Everyone on the ground has to fight these like they are going to turn into it. And the whole point is to just sell the idea.”

Keerit Jutla, president and CEO of the Association for Mineral Exploration British Columbia, said the association is reviewing the report, but the current tax regime has been critical to the country’s status as the world’s number one destination for investment in mineral exploration.

“There is no net tax leakage under this 60-year-old tax incentive, proven over time to be beneficial to all,” Jutla said.

Mining tax incentives make ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ global leader, says industry

Nearly half of the world’s mining companies are legally , more than triple that of the United States, the next most popular jurisdiction.

One way mining companies have kept afloat in the early mineral exploration stages, an inherently risky business, is through the prospect generator model, which allows investors to finance junior mining companies focused purely on exploration. Those companies leave the later stages of mining to other companies.

In ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, a key to raising money is the federally backed flow-through share tax regime.

Somebody who invests $10,000 into a flow-through share deal can at the same time take $10,000 off the taxable income they report to the government at the end of the year, according to Jeff Killeen, director of policy and programs at the Prospectors and Developers Association of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

Killeen said owners of junior mining companies and often institutional investors take advantage of flow-through shares. The most common purchasers of flow-through shares, added Jutla, are “high net worth investors in urban ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.”

Together with other federal and provincial tax credits, investors often end up paying roughly a third of the purchase price of the shares, Killeen said. The rest is .

Advocates of mining tax incentives say they have proven to be very effective — insulating ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s mining industry from risk, while garnering investment and spinning off economic development across ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s rural and northern areas.

But detractors say the public cost to bolster early-stage gold mining is too high, and both people and the environment are paying the price. The report singles out several companies as examples of how the prospect generator model benefits those involved at a high cost to taxpayers.

Tax incentives allow long-term bets, big rewards, says Victoria-based mining owner

One company, Teuton Resources, was founded in 1980 by now president Dino Cremonese, and claims to be “one of the first to use the prospect generator model,” according to its website. The company’s head office — which is shared with Silver Grail Resources — is listed at a waterfront detached house overlooking Harling Point.

A significant portion of Teuton’s assets are held in a joint venture with Tudor Gold. In 2022, that company sold $13.3 million in flow-through shares at a taxpayer cost of roughly $7.4 million, the report says.

Then there’s executive payouts. In 2022, the report says Teuton Resources paid Cremonese a salary of $187,500, engineering fees totalling $55,189, and $4,800 in rent, “presumably because the companies’ office doubles as his home,” the report says.

In addition to the cash payouts, the report said Teuton Resources regularly issues stock options to its executives, including $1,878,064 in share-based compensation to directors of the company in 2022.

But as Teuton has paid out its executives and spent more than $50 million in 40 years of exploration, the company’s annual reports show it has failed to generate revenue, the EIA report claims.

When reached for comment, Cremonese said the EIA analysis fails to understand just how risky mining exploration is and how big the long-term payoff can be. Some mineral deposits in the Golden Triangle have produced revenue for decades, he said.

“Finding mines is a difficult business. That’s why the government has offered tax incentives by way of flow-through shares,” said Cremonese. “I emphasize that the win to society from those who are lucky or skillful enough to come up with a mine makes up for all the losses incurred by those who don’t.”

The companies Cremonese has been involved with — including Teuton and Silver Grail — “have led to over $200,000,000 in exploration in the Golden Triangle” in work that has employed thousands of people, said Cremonese.

“I staked Treaty Creek in 1984 and today the property has two published resource estimates after [more than] $100 million in exploration. Another property I staked, Red Mountain, has already received federal and provincial approval,” he said. “It takes a long, long time from first staking to production.”

Alaskans worry mines will send more pollution over the border

The Golden Triangle is currently home to over 100 mining projects in some phase of exploration, proposal or operation, the EIA found. Of all the claims in the transboundary region, 80 per cent are within five kilometres of a river or stream.

But many Alaskan communities and tribes living downstream of mines and mineral prospecting have not been properly consulted, said Heather Hardcastle, a campaign advisor with the Juneau-based advocacy group Salmon State, which commissioned the investigation.

“Our biggest concern is pollution. And essentially, we're shut out of the process right now. Meanwhile, this whole region, it would seem, has been industrialized,” said Hardcastle.

“Just something like one U.S. penny made of copper in one Olympic-sized swimming pool would be enough to interfere with the navigation system of salmon.”

Even if mines aren’t ultimately developed, Hardcastle worries the thousands of kilometres of exploratory borehole drilling could contaminate waterways vital to fish.

Another growing concern: 18 per cent of mineral claims in the area are covered by glaciers. That’s a problem, said Hardcastle, because as those glaciers melt under a warming climate, they will open up a cold water refuge for salmon in direct conflict with mining claims.

In 25 rivers in the transboundary region, more than half of future salmon habitat was found to lie within five kilometres of a mining claim, found a November 2023 peer-reviewed study published in Nature.

Retreating glaciers offer a “second chance” for salmon being squeezed by overfishing and climate change, said author Jonathan Moore. But he worries the trajectory of the emerging ecosystems has been set by mining companies interested in speculation and market prices, rather than ensuring the health of salmon.

“These are places that are the size of some countries in Europe,” said Moore at the time. “It could be tens of thousands of fish returning to any given one of these watersheds.”

The multi-pronged conflict has sent mining interests, fish, Indigenous groups, environmentalists and fishermen on a collision course. In recent months, concerns on the Alaskan side of the border have reached one of that state’s highest offices.

In a September 2023 , Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski called on U.S. President Joe Biden to suspend U.S. assistance to Canadian mining operations in the Golden Triangle region “until Alaska’s long-standing requests for international cooperation have been addressed.”

Murkowski pointed to the Mount Polley mining disaster in 2014, when a tailings dam released 24 million cubic meters of mine waste into the local waterways in the worst environmental mining disaster in Canadian history.

“Worse still, since the 1950s, the abandoned Tulsequah Chief Mine has leached polluted runoff into waters that flow into the Taku River, which in turn flows into Alaska, where it is one of our most important salmon-bearing waterways,” wrote Murkowski.

“Despite decades of promises from British Columbia that the Tulsequah Chief will be cleaned up, little has changed, and now ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is planning new mines right in its vicinity.”

Michael Goehring, president of the Mining Association of BC, said claims that the province’s mining industry is not consulting Indigenous groups on the Alaska side of the border are false.

In response to Murkowski's concerns, in December 2023, Goehring sent a letter to Alaska’s two senators and 40 House of Congress representatives noting, among other things, that one ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ mining project proponent made “substantial adjustments to their water management approach” after consulting Alaskan tribes.

In a statement to Glacier Media, Goehring said the EIA report contains “inaccuracies,” is “misleading” and based on “flawed research.”

Those on the U.S. side of the border, however, aren’t the only ones pushing back. ​

​'Right to be concerned'

Nikki Skuce, co-chair of the BC Mining Law Reform Network, said the findings from the EIA paint a portrait of a mining industry where “storytelling gets a few people paid.”

Last year, Skuce's organization pointed to from 2022 when more than 40 per cent of the amendments ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ mines requested under the the province's environmental assessment process were approved — even though they were “likely to have negative impacts on” effluent discharge, lead to the extraction of more water, or degrade fish habitat.

At the time, Skuce said the “systematic problem” came from a culture of industry and government believing it has the best mining standards in the world. Today, she said, little has changed and the Golden Triangle region remains in crosshairs of exploration companies.

“Alaskans, they are right to be concerned,” said Skuce, who was not involved in the report.

“There's definitely been like a modern day gold rush up there. Except for the handful of protected areas, like most of the region has been staked, including on glaciers.”

ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s mining industry claims to be pivoting toward critical minerals. But Skuce says most in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ still target gold under a Mineral Tenure Act that has allowed companies to stake claims on roughly 76 per cent of the province’s lands without consultation with First Nations.

That precedent came crashing down in September 2023, when the Gitxaała Nation won a judicial review that found companies do have a duty to consult with First Nations.

The ruling directed the province to create a new claims-staking system over the next 18 months. But the authors of the EIA report say the majority of the Golden Triangle area is already claimed and won’t be challenged under the new system.

Glacier Media reached out to Natural Resources ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation for comment on the EIA's investigation, but neither responded by the time of publication.

“It seems like this is a way to have a coordinated approach to reduce your tax burden, to make a lot of money and, cause environmental damage, but not necessarily have to deal with any of the risk from it,” said the EIA’s Harry.

“It can make a lot of money for a very few and not really deliver anything — other than just the prospect of the prospect.”