Come October, those British Columbians who haven’t already voted with their feet may be voting with their wallets.

That is – they may be casting their votes according to how light their wallets have become in the Oct. 19 provincial election.

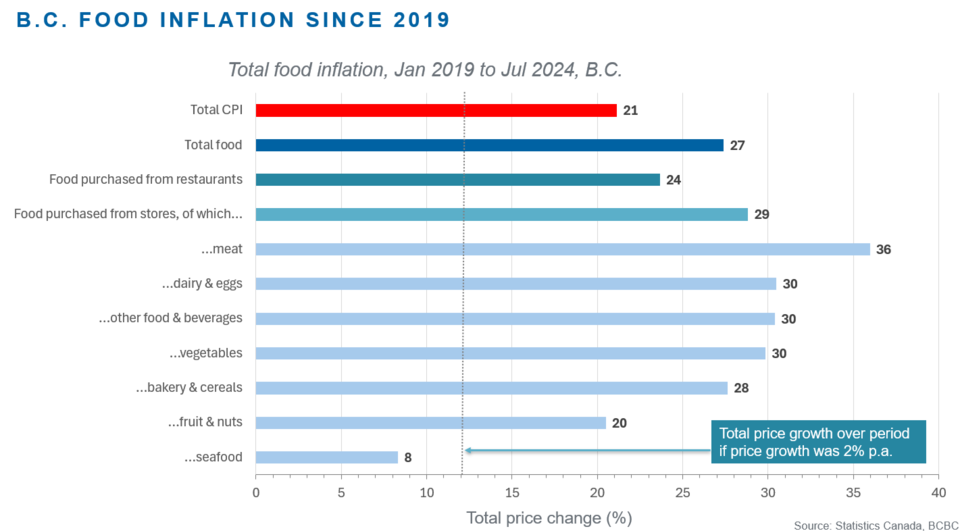

A recent analysis by the Business Council of BC (BCBC) finds that it costs the average consumer 21 per cent more to live in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ in 2024 than it did in 2019. The analysis is part of the the BCBC’s series.

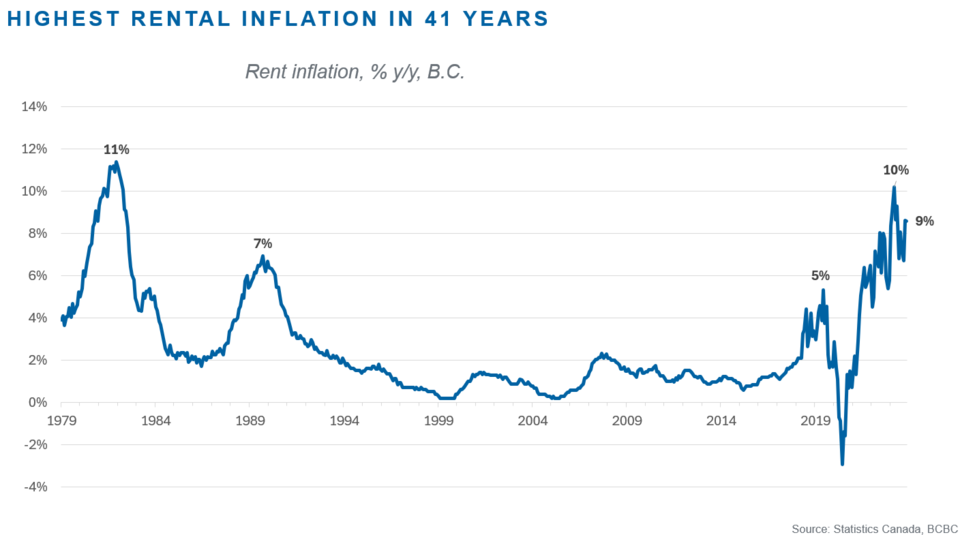

The two most important necessities – food and shelter – are up 27 and 29 per cent, respectively, since 2019.

There has also been a 49 per cent increase in home and mortgage insurance costs and 33 per cent increase in property taxes since January 2019, the BCBC report notes.

The report points to a recent Angus Reid poll that found that many British Columbians have already left ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ due to the high cost of living – especially the high cost of housing – as an indicator that the high cost of living in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ will be an issue for voters in the provincial election in October.

“In 2023, the province lost 8,000 more residents to other provinces than it gained, an inter-provincial net loss not seen in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ since 2012,” Angus Reid said in a June report. “Further, more than one-in-three (36 per cent) say departing ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is something they’re giving serious consideration to because of housing affordability.”

"British Columbians are grappling with the effects of significant price increases across nearly every facet of life," BCBC vice-president of policy David Williams said in a press release.

"As political parties prepare for the provincial election, it's crucial they focus on policies that help ease cost-of-living pressures. A good place to start is fiscal discipline."

The BCBC analyzed Statistics ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s Consumer Price Index (CPI) data, and found that the price increases for six out of eight major product categories rose faster than the Bank of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s two per cent per annum target for national CPI inflation.

Government spending can contribute to inflation, and in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s case, the provincial government has resorted to deficit spending, which ultimately leads to higher debt servicing costs when interest rates rise. ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ also risks credit rating downgrades, which also raise the cost of borrowing.

“ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s annual inflation is running at the second highest in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ at 2.8 per cent as of July,” Williams said. “The projected provincial budget deficit for this fiscal year is 1.9 per cent of GDP, which is larger than the deficit of 1.8 per cent of GDP recorded in 2020/21 during the COVID-19 emergency.

“The unemployment rate was 13.3 per cent during COVID-19 compared to 5.5 cent now, so it’s hard to justify injecting emergency-levels of fiscal stimulus into today’s economy.”