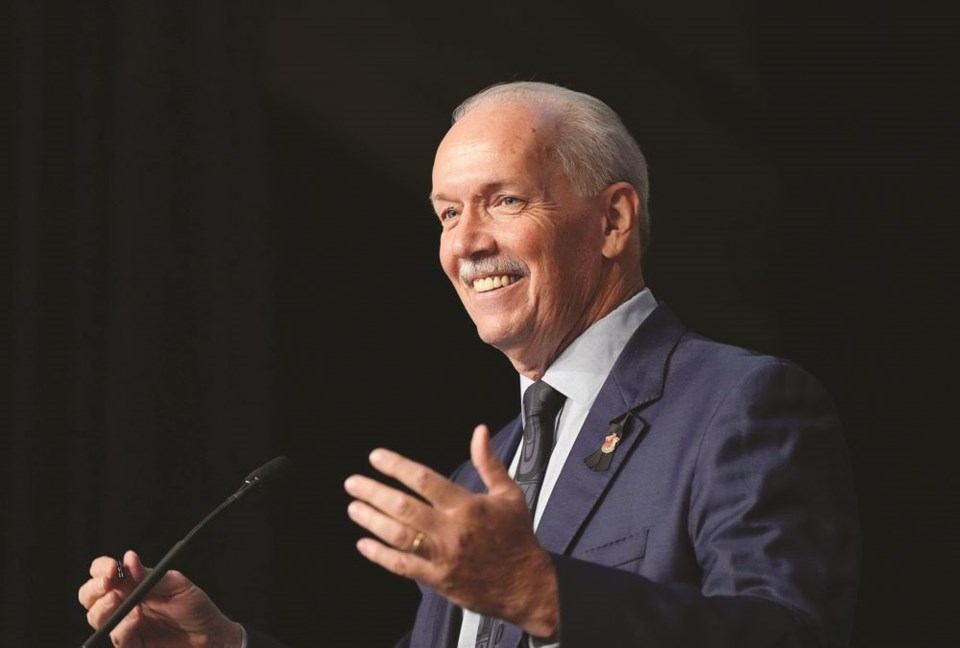

I’d be surprised if anyone could show me many pictures in which John Horgan wasn’t at least somehow modestly beaming.

I’ve gone through the file photos of him: smiling here, chuckling there, laughing hard, sharing a joke, making mischief, cracking the slightest of smiles even when the situation might have called for a straight face. Only when the most solemn occasions utterly required it did he not display the contagion of his innate good nature and the joy of service grounded in his whimsy.

Horgan, British Columbia’s 36th premier, was beloved as the leader you wanted to have a beer with, the country’s best-regarded first minister, and could have held his accidental role indefinitely were it not for the scourge of cancer that in its third round took him down Tuesday at age 65.

Born in Victoria, raised by a single mother of four – his father died of a brain aneurysm when John was 18 months old, and he revered older brother Pat, another cancer victim who passed in 2018, as the father figure in his life – Horgan leaves his love-at-first-sight wife Ellie and sons Nate and Evan. He worked his way through university, up the public service to be chief of staff in premier Dan Miller’s office, then into an associate deputy minister role before entering the legislature in 2005.

It is legend that he made the most of a role he didn’t want – that he needed to be coaxed to take the BC NDP leadership when no one else would, and that in securing the premiership he found a popular formula to mix fiscal competence with social prescription, able to develop mutual respect for business and labour alike.

He had his share of the limelight, but gave his ministers more than theirs. He loved the saying “show your work,” to demonstrate the steps taken to arrive at a decision. He had an uncanny common touch. I remember sitting offstage with him at an event, after I’d moderated a panel and he was waiting to speak. He got up on his feet to approach the podium, then came back to me as a fellow Canucks fan and whispered: “Meant to tell you, you were right about Edler on Twitter the other night.”

It should be noted that he was not always perceived as the iconic hail-fellow-well-met politician. Along the way he had to shake the image as a nasty, caustic adversary of government in the legislature – Hulk Horgan, he was, or “Angry John,” the timbre in his catcalling a defining characteristic of an opposition leader straight out of central casting.

“It was my job, it’s what you have to do,” he told me once. “I had to be Dr. No, the guy who was always complaining and criticizing. It was what was expected of me,” then added, “and it isn’t me,” something we learned later.

Historians might argue differently, but I’ve always thought the turning point of the career in public life, the catalyst to the premier’s office, involved a simple promise in the middle of what had been a heading-nowhere 2017 campaign: no more bridge tolls. It caught the government flatfooted and caught the commuters’ fancy. It reinvigorated the BC NDP’s flagging fortunes, even if it didn’t at first deliver government.

Remember, Christy Clark’s BC Liberals won two more seats than the BC NDP, but she could not cinch the deal with then Green Party leader Andrew Weaver and the other two Greens. Horgan and Weaver forged a confidence and supply agreement to outnumber the BC Liberals by one. When the first opportunity arose – an amendment to the BC Liberals’ Speech from the Throne – the two parties combined and made the Clark government the first ever in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ to be defeated in the legislature. She resigned shortly after.

Horgan only grew after that, even with a threadbare majority, even when he flip-flopped and stunned some supporters to back the Site C hydro-electric mega-project. Against some advice that it would seem too opportunistically early in the pandemic to call a snap election – the first in nearly 35 years – it yielded a sizeable majority.

In office, he moved the BC NDP toward but not smack-dab into the meaty, sweet-spot centre. With a close ally in then finance minister Carole James – she had been party leader when he first entered the legislature in 2005 – he maintained the balanced budget about which the BC Liberals had been so proud. He shifted medical service premiums to employers, reformed the financial mess of ICBC, and kept the province’s credit rating even as it furnished financial support in the pandemic.

To please his base, he promised to do everything in his power to stop the Trans Mountain pipeline twinning, but knew that doing everything in his power would never do more than stall the inevitable. He loved telling the story of a press conference with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in which he accidentally knocked over a glass of water, and declared: “Spills can happen anywhere.”

A second bout of cancer in 2021 prompted 35 radiation treatments. He stepped down as premier once he was cancer-free in 2022, then resigned his seat in 2023, only to resurface months later to take the role of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s ambassador to Germany – not particularly the ideal Ireland post, but endlessly fascinating for a master’s graduate in history. He was flown home Friday, a third bout consuming him.

He was the NDP’s first two-term premier and remains, for the time being, its longest serving.

Had he stayed as premier, it is reasonable to presume that the 2024 election would have been much different. Would Kevin Falcon have been better suited to be his legislature foe, rather than David Eby’s, and kept his BC United party alive? Would the Conservative Party of British Columbia have risen so quickly as an antagonist? Would the BC NDP under him have faced the same depth of concern about the economy that has pressed Eby?

Eby has found Horgan a hard act to follow. The premier cites Horgan as a mentor, but to me they seem such different souls, one practised in personal connection and the other practised in policy construction. It reminds me of a concert I saw in 2002 headlined by Moby; fair enough, but the act that preceded him was the one and only David Bowie.

Kirk LaPointe is a Glacier Media columnist with an extensive background in journalism