Boreal forests and their peatlands are one of the largest natural absorbers of carbon on the planet. But as climate change heats up northern latitudes, that carbon sink is increasingly at risk of going up in smoke.

A published earlier this month in the journal found the 2021 boreal wildfire season released a record 480 megatons of carbon — far more than the from ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s oil and gas sector, transport and buildings.

The fire season, which stretched across boreal forests in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, the U.S. and Russia, could be a sign of things to come, concluded the study.

“Boreal forests could be a time bomb of carbon, and the recent increases in wildfire emissions we see make me worry the clock is ticking,” said Steven Davis, one of the study’s authors and a professor of Earth system science, in a written statement.

Davis, along with 17 other researchers involved in the global study, used satellite data to measure carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide emissions over the past two decades. In 2021, they found wildfires emissions spiked two and a half times higher than the average going back to the turn of the millennia, when satellite measurements began.

But the single mega-fire seasons wasn't the only signal they found: between 2000 and 2021, the satellite data showed wildfire emissions increased at an average rate of 4.5 megatonnes per year.

“It’s not only 2021,” said Yang Chen, a wildfire researcher at University of California Irvine and another co-author on the study. “When we look at the past 20 years, we see a clearly increasing trend in emissions, and in the future, with further warming, the scenarios like 2021 will occur more frequently.”

Jennifer Skene, a forest and climate policy expert at the Natural Resources Defence Council’s ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ program, said the study’s conclusions were worrying.

“The numbers are staggering,” she said, “but not all together surprising given that we’ve seen over the last decade increasing wildfires — not just in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ but across the boreal in general.”

Some regions of the northern forests have been hit harder than others. Overall, the 2021, the Eurasian boreal wildfires released the most carbon. And Skene said in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, boreal wildfires have been much more frequent in Western ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, including northeastern ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and Alberta.

She pointed to 2016, when a powerful fire ripped through Fort McMurray, Alta., prompting the evacuation of 88,000 people.

Eighteen months after the fire, nearly half of surveyed elementary and high school students met the criteria for one or more , depression, anxiety, or alcohol and substance abuse.The fire remains the most expensive natural disaster in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s modern history.

Canadian boreal holds double the carbon of world’s oil reserves

Boreal forests are the most carbon-dense terrestrial ecosystem in the world. A hectare of boreal forest stores double the carbon found in a hectare of tropical forest. That means that in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ alone, there is twice as much carbon dioxide locked up in the boreal biome as all the world’s oil reserves combined, says Skene.

“It’s hugely significant,” she said.

When those boreal forests burn, they release up to 20 times as much emissions as grasslands, according to Chen and Davis’s latest research.

A majority of that carbon gets sucked up by vegetation when things slowly grow back. But 20 per cent of those gases stay in the atmosphere “much longer,” adding to a buildup of carbon dioxide put there by humans, according to the study.

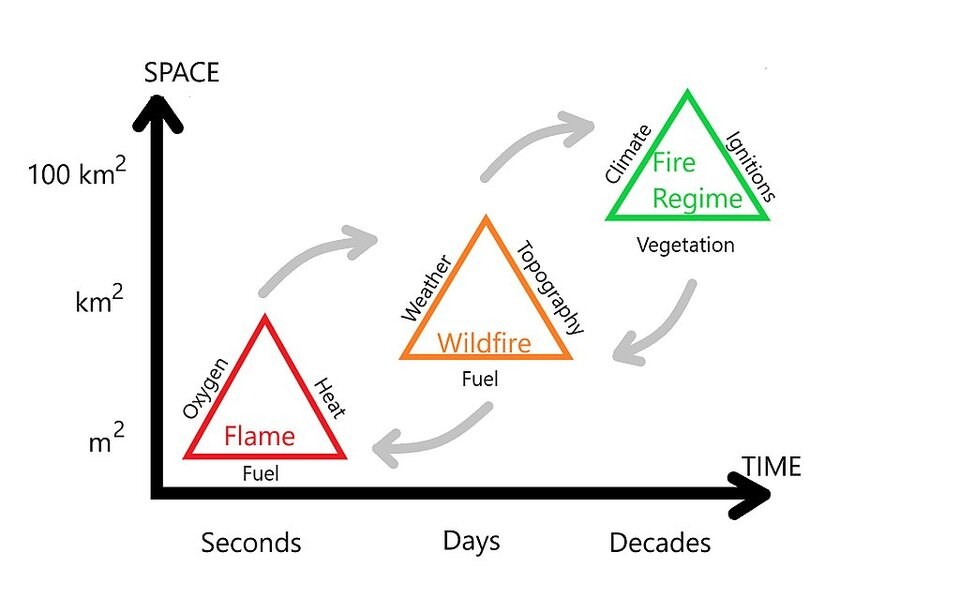

‘Fire triangle’ growing more powerful

First you need to have the right conditions. Prolonged drought, fuel and a source of ignition make up what experts describe as at the ‘fire triangle.’ Have all that at once and you have everything you need for a conflagration like that seen in 2021.

That year, Chen and his colleagues found the first point of the triangle — severe heat waves and droughts hit both North America and Eurasia at the same time.

Hot, dry conditions are expected to increasingly grow more entrenched in the coming years. Much of the increase in emissions from wildfires is expected to occur north of 60 degrees, a line of latitude that separates ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ from Yukon and the Prairie provinces from the Northwest Territories.

At those northern latitudes, Chen says global warming is setting the conditions for more vegetation to grow, offering more fuel to increasingly dry conditions.

“You have to have ignition, you have to have fuel, and you have to have dry fuel,” he said. “We call it the fire triangle — it all depends on the warming caused by fossil fuel emissions.”

On the ground, Skene says forests are also being primed to burn by logging activities.

“Once a forest has been cut, it’s much more vulnerable to these impacts,” she said.

All that’s missing is a source of ignition. Last year, Chen lead a study that found the in northern boreal forests could more than double by the end of the century.

The lightning, found the study, could create a “fire-vegetation feedback” loop, leading to the burning of more Arctic tundra and the release of carbon from permafrost soils.

“In the tundra region, there’s not much vegetation,” said Chen. “But with future warming, that vegetation can grow on those tundra regions and the lead to more fuel.”

“I don't think people are paying enough attention to these emission from fires.”