A high-pressure system launching temperatures into the double digits across British Columbia has been made between two and five times more likely due to human-caused climate change, according to an ensemble of climate models.

By Friday, temperatures in Squamish reached 26.5 degrees Celsius, for a time, the hottest in the country and potentially a daily record, according to Derek Lee, a meteorologist with Environment ��ѻ��ý.

“Right now, we’re looking at near records for Vancouver and Nanaimo,” he added.

The hot weather dominating much of the southern half of the province is expected to continue throughout the weekend. climbing to 23 C in Nanaimo, 21 C in Victoria and Vancouver, and 25 C in inland areas of the Lower Mainland such as Coquitlam, according to the national weather agency. In the Interior, temperatures could shoot up to 27 C in Kelowna, and up to 29 C in Kamloops.

“At this time of year, six to 10 degrees Celsius above normal across the whole South Coast is abnormal,” said Lee, noting official temperature records are confirmed the next day. “Whether or not it breaks a record, we’ll see.”

Warm weather triggers avalanche warnings, river advisories

Warm temperatures have triggered melting at higher elevations, prompting the to issue high stream-flow advisories across much of the Upper and Middle Fraser, Thompson, and Okanagan watersheds.

“River levels are rising or expected to rise rapidly. Being near these riverbanks, creeks and fast-flowing bodies of water is dangerous,” warned the centre Wednesday.

On Thursday, Avalanche ��ѻ��ý issued a special public avalanche warning across the western half of ��ѻ��ý.

"A dramatic increase in temperatures is expected to destabilize the snowpack across western ��ѻ��ý, resulting in dangerous, destructive avalanches," the alert reads.

The hazard will only increase with each day of warm air, the bulletin added.

By late afternoon Friday, ��ѻ��ý's warmest temperature was recorded at the Hope Airport, where it had climbed to 27.7 C.

Climate change making warm temperatures more likely, models show

For the first three weeks of April, much of ��ѻ��ý had experienced a relatively cool spring, according to Environment ��ѻ��ý research scientist Nathan Gillett. Now, in the province's capital, Victoria, where he lives, “We are close to the historical maximum,” he said.

In the past, determining how much of the unseasonably warm temperatures are being made more likely by climate change would have been nearly impossible to answer. But new nearly real-time models have changed that.

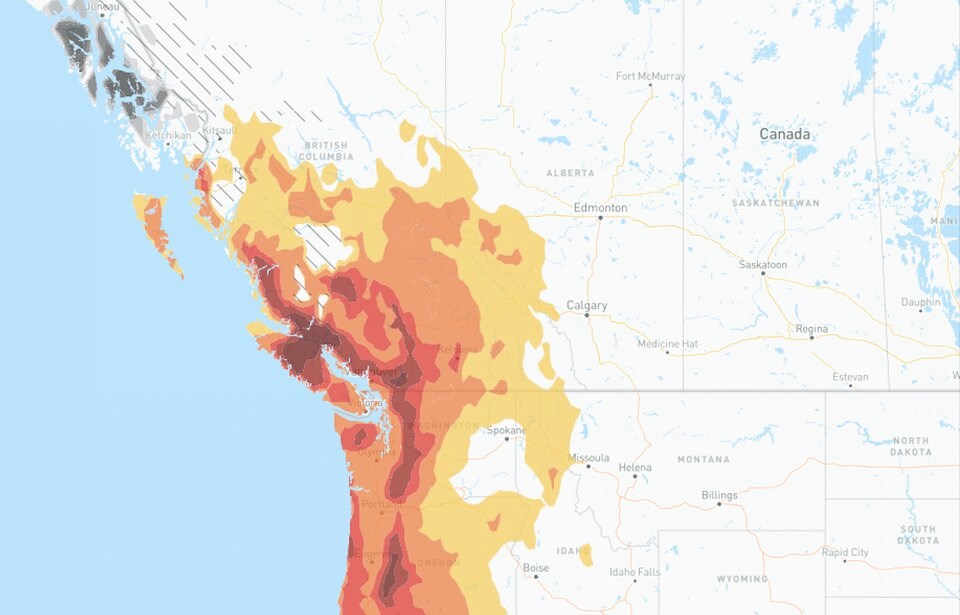

As of Friday, temperatures across southern ��ѻ��ý were made between two and five times more likely due to climate change, according to the (CSI), a rapid attribution tool produced by the U.S.-based Climate Central research group.

To take climate change's real-time fingerprint, CSI uses a peer-reviewed process that compares observed temperature data with models that estimate how the weather would behave with and without human-caused climate change.

At zero, the influence of climate change on weather conditions, such as a daily high or low temperature, is not detectable. At this point on the scale, the prevailing weather is as likely to proceed with or without the effects of climate change.

A CSI of +1 indicates climate change has made weather 1.5 times as likely; at +2, a strong effect from climate change has made weather twice as likely; at +3, a very strong climate fingerprint has made the prevailing weather three times as likely; and at +4, weather conditions have been made four times as likely, or “extremely rare without climate change.”

At +5, an “exceptional” climate change signal indicates weather conditions have been made at least five times more likely, “potentially far more,” states Climate Central’s CSI scale.

The CSI map showed large swaths of Vancouver Island the Central and South Coast and Fraser Valley glowing a dark red Friday — indicating current conditions would be “extremely” or “exceptionally” rare without the influence of humans on the world climate system.

Gillett, who was not involved in producing the tool, described it as “credible.”

“The climate models project the strongest warming is in the winter,” he said. “We should expect more of this.”