Some nurses answering the province’s call to return to their profession or upgrade their skills say they are hitting roadblocks.

They’re asking for the option to upgrade or refresh their skills on the job, so they don’t have to leave an already strained workforce for long periods of study.

Last year, the province announced funding for bridging programs for licensed practical nurses who want to become registered nurses. An LPN in a bridging program would typically be able to do a bachelor of science in nursing degree in two or three years, rather than four.

A bridging program to be offered at Camosun College starting in September, however, requires applicants to have completed a two-year LPN course. Yet, prior to 2012, Camosun only offered a one-year LPN course. Because of the two-year requirement, many working LPNs are ineligible, despite having years of work experience.

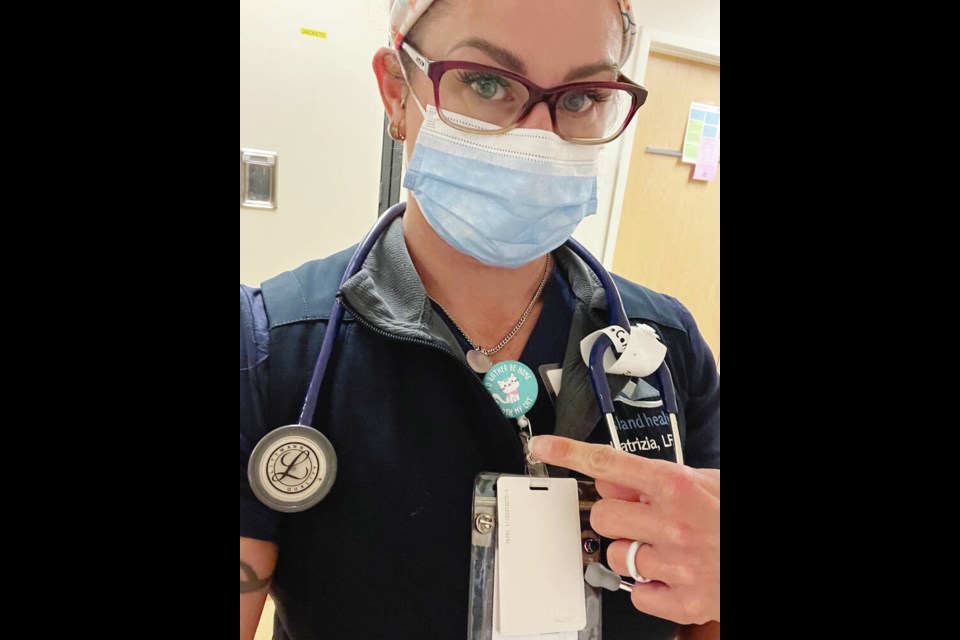

Patrizia Maier, who works as an LPN at Royal Jubilee Hospital, was a single mother with toddlers when she took the 12-month LPN course at Camosun College. Thirteen years later, she’s worked in all areas of health care as an LPN, the last three in acute care in renal dialysis.

She thought the bridging program was great news, but now faces having to retake the two-year LPN course or contemplate a four-year registered-nurse course.

“We have families and kids, and we still need to be able to work while doing that … so if we went back to do the four-year RN program, for example, that’s four years of student loans and not being able to work for the first two years,” said Maier.

Having mentored nursing students and worked alongside RNs for more than a decade, she’s “more than frustrated” that she’s not eligible for Camosun’s bridging program and that there’s not an apprentice-style training alternative.

Tess Hunter was on a waitlist for the four-year bachelor of science in nursing program in 2011 when it was suggested she take the 2011-2012 LPN course at Camosun. She’s been working as an LPN in acute care since she graduated.

“We didn’t know that a new two-year LPN program was coming out the next year — otherwise I would have just stayed on the waitlist for the RN program,” said Hunter.

She thought the LPN course might be a good way to test how much she enjoyed nursing while she was waiting, “not knowing that I’d basically be pigeonholed into always staying an LPN.”

A top-level nine-year LPN makes $34 an hour, versus $57 an hour for a similarly experienced registered nurse, according to Island Health, although the average front-line nurse, what’s called a Level 3 nurse, with at least nine years’ experience earns $47 an hour.

Hunter wrote to Camosun for clarification, but was told by Dwayne Pettyjohn, associate dean of health and human sciences at the college, that the admission requirement of a two-year diploma would stand.

In an interview, Pettyjohn said applications are not yet being accepted for the bridging program while the college works through approval processes. Once that’s completed, “there may be some modifications to our program,” he said, and updates will be posted on the college’s website.

Vancouver Island University accepts bridging students from an “accredited LPN program” who have been recently employed in their field. It does not require a two-year diploma.

There are nine bachelor of science in nursing programs at public post-secondary institutions in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ that have, or are developing, LPN-RN bridging programs.

On the Island, besides Camosun and VIU, that includes North Island College, which has an LPN bridging program in development that aims to include part-time elements so that people can continue to work while studying.

It’s the kind of approach that Maier and Hunter would like to see in Victoria.

“We’re in a staffing crisis,” said Hunter. That makes it imperative to provide more ways for LPNs to train to become RNs, and ways that include being able to continue working, she said.

The Health Ministry said it’s aware many LPNs continue to work when they go back to school, “which is why increasing the number of bridging programs around the province has been a priority.”

As of March 31, 2022, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ had 4,265 vacant nursing positions — three quarters of them for registered nurses, 20 per cent for licensed practical nurses, and some for nursing supervisors, according to Statistics ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

This month, the province dropped registration fees , announced $4,000 to cover assessments and travel, and $10,000 bursaries for retired registered nurses to re-enter the profession.

It’s spending $96 million over three years to increase health training spaces, including 602 new nursing seats (362 RN and 180 LPN) in addition to the 2,000 seats currently in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ nursing programs.

“We will continue looking for opportunities where there are barriers, with our partners at the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ College of Nurses and Midwives, to make life easier for health-care workers as they strive to serve patients in the province,” the Health Ministry said.

ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Nurses’ Union president Aman Grewal said the union, currently in negotiations with the province for a new collective agreement, has long advocated for bridging programs that include on-the-job training. “We can’t afford to lose any of these LPNs from health care right now. They need to be able to do their training and get paid while they’re doing it because they can’t afford to lose money either.”

Grewal said since many LPNs have worked many years and “have a wealth of experience and knowledge,” there needs to be an LPN to RN program that includes a portion of paid time off with a majority of the upgrading done through on-the-job training and online. If it can be done for student nurses doing practicums “why can’t we do that with professionals already working in the system?”

Athabasca University in Alberta has that kind of LPN to bachelor of nursing bridging program, which has attracted ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ nurses, but they often have hurdles trying to return to practice in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, “which makes no sense once again,” Grewal said.

Meanwhile, a Saanich RN who left her profession in 2003 to raise her son who had a disability and returned two years ago to work during the provincial immunization program, said she has tried unsuccessfully for a year to reactivate her licence. She asked for her name to be withheld to avoid reprimand.

The ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ College of Nurses and Midwives requires 1,200 “practising” RN hours to reactivate a licence that has lapsed for five years or less. For licences that have lapsed for longer, nurses must be reassessed. The Saanich nurse’s hours are considered “non-practising,” even though she performs the same work administering vaccines as her colleagues.

The college says immunization nurses working under a provincial health officer order are limited in their role and do not practise full scope or independently.

Grewal agrees there’s no difference between a practising and non-practising nurse giving immunizations, but cautions “if you’ve been out of the workforce let’s say six, seven years and you’re next to an ICU nurse, you’re going to want a refresher.”

The problem, however, is that there is no nursing refresher course on Vancouver Island, according to the nurse.

That shows the need, once again, for an on-the-job refresher, said Grewal.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]