Damon Langlois learned his most important sand-sculpting lesson early and never forgot it: If something goes wrong, start again and finish the job.

Working with sand means accepting the risk that a painstakingly crafted sculpture could suddenly collapse.

“People don’t become sand sculptors if they’re not willing to face that risk,” said the View Royal resident, who will be competing in the solo category in the sandcastle competition at this year’s Parksville Beachfest, which opened Friday at Parksville Community Beach and Park.

Sand sculptures can collapse for a variety of reasons. It might be due to a mistake in carving, or misjudging the sand as the sculptor pushes the boundaries of what the material can do.

Sometimes, it’s just because of the weather — rain might weigh down a sculpture and cause it to crack.

An experience in Kuwait a decade ago drove that point home for Langlois, 53, who has won five world-championship awards — four as part of a team called the Sandboxes and once as a solo competitor.

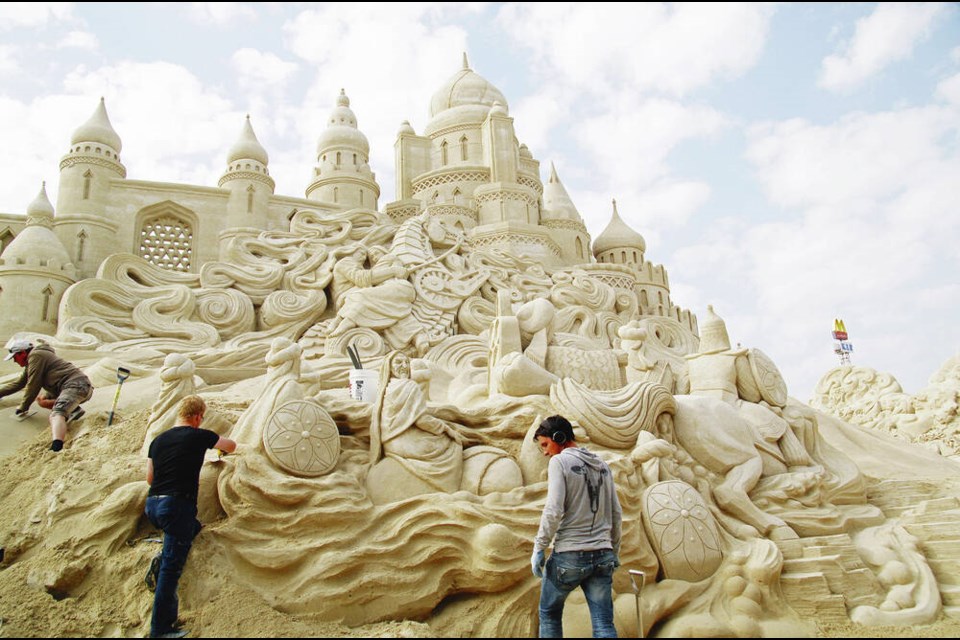

Langlois, who has his own industrial-design company and builds sandcastles on the side, had been hired as the art director for massive Arabian Nights-themed sand sculptures at the Remal International Festival on a site measuring the equivalent of six football fields in the desert.

But about halfway through construction in the winter of 2013, a “relentless” three-day deluge washed away a large portion of the work.

It destroyed some heads and wiped away faces of sculptures and took up to two metres off the tops of some of the works.

Just before the storm hit, Langlois remembers walking through the site at the end of the day and seeing everything coming to fruition after many months of planning.

“It is actually happening. It’s real and it’s just so unbelievable,” he remembers thinking. “Your heart is overwhelmed by pride and literally tears coming to the eyes.”

But the rainstorm hit at the end of the following day. “There wasn’t really a lot of warning at all for the storm … We weren’t really ready for the degree that it hit.”

He went to the site on the second day as the storm continued to rage, watching it “tear apart the sculptures.”

When the rain finally stopped, a crew of 10 people went in to to clean up the mess.

Viewing the devastation, “wasn’t easy to deal with by any stretch. It’s also what makes the whole thing so powerful … We did just go in … We had to recover.”

Cleaning up the site and resuming their task was a “logistical nightmare” given the scale of damage and the fact that workers did not have all the equipment they needed on hand — including equipment for spraying the diluted glue that helps preserves the sculptures.

One container of materials had been sidetracked by customs.

International sculptors were landing in Kuwait at the same time as organizers were reworking what had been a precisely planned program for staging and setup.

Langlois said he rallied the 70-person team by giving them what he calls his “football-coach speech,” and they were able to open on time in January 2014.

To commemorate the event and to showcase the grand and elaborate sand sculptures, Langlois has put together a limited-edition hardcover book, launched through a kick-starter campaign.

It features photographs of the sculptures, addresses the challenge of recovering from the storm and includes 32 stories from the Arabian Nights collection.

The year after the Kuwait show, Langlois and a partner built what was at the time the world’s tallest sandcastle in a competition at Miami Beach.

Standing 13.97 metres, it featured a castle surrounded by world monuments.

Langlois, who moved to the capital region from Alberta with his family in 1979, said he was artistic as a child.

He later earned a degree in industrial design at Carleton University and today runs his own company, Codetta Product Design. Products include consumer electronics, fixtures for public utility companies, medical equipment and products for the music industry.

While he was in his early twenties and working as an industrial designer in Victoria, a colleague invited Langlois to join a sand-sculpting team competing at Harrison Hot Springs, where they won second place.

That was a little more than 30 years ago. “At that point I was hooked,” said Langlois, who placed fourth in solo competition in Texas SandFest earlier this year.

What appeals to him about sculpting sand? “It’s just really hard to describe … when you’re doing it, you’re just really in the moment. I used to call it intense relaxation.

“There’s nothing like it because you are engineering on the fly.”

Langlois is often asked how he can put so much effort into something that’s just going to wash away.

That’s just part of the “Zen of sand sculpting,” he said.

“You have to have this kind of an acceptance of that,” he said. “It’s the journey, right?”

When a sculpture is completed, the diluted glue is mixed with water to put a “skin” over it, but the coating has no structural element to it. “It just protects it against a certain amount of rain and wind.”

Today’s sculpting scene is more professional than when he started, Langlois said.

At that time, sand sculpting was growing on the West Coast while at the same time a beach-busking scene was bubbling up on the East Coast, he said.

“That in itself created this kind of boom, because all these influences really started to get amplified.”

North American sculptors travelled to Europe to train others.

Langlois estimates the average age of sand sculptors today is about 60.

“In part I would attribute that to the amateur scene that was here in the Pacific Northwest with the world championships and lots of amateur sand-sculpting competitions on the beach … This is all coming out of the ’80s and ’90s.”

Experienced competitors like Langlois are invited and paid to travel to major competitions, where they’re put up in hotels and paid a wage by the organizers.

They also sometimes carve snow and ice and do other forms of sculpture and may offer lessons and workshops. Langlois said he tried snow carving once and plans to stick to sand.

He said he normally goes to about three competitions per year, along with attending exhibitions.

He’s found inspiration in a wide range of subjects, from Frankenstein to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, fantastic creatures and instantly recognizable figures.

In the piece that won him the solo competition at Texas Sandfest in 201, an anguished Abraham Lincoln is seated with his hand over his face. It was titled Liberty Crumbling.

When he’s creating a sculpture, Langlois said, “I like to play with things that have some kind of emotive responses to them … There’s some deeper meanings to them.”

He created Liberty Crumbling at a time when there was an “edginess” around the world, Langlois said, including events such as protests in Hong Kong and Venezuela.

‘The greatest thing about that sculpture is that lots of people took it in their own way and I think that’s the real gift.’

• On youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ZwZr5cuZWs

• To obtain a book go to https://storiesinsand.com. The $120 price includes shipping.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]