The Modern History Gallery opened on the third floor of the Royal British Columbia Museum to great fanfare on July 7, 1972.

Thousands of people streamed through the doors and up modern escalators for a dive into ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s past that summer.

And millions have followed since.

It was the first permanent exhibit for the museum’s new building, which had been completed in 1968 as a Centennial project, across the street from the provincial legislature.

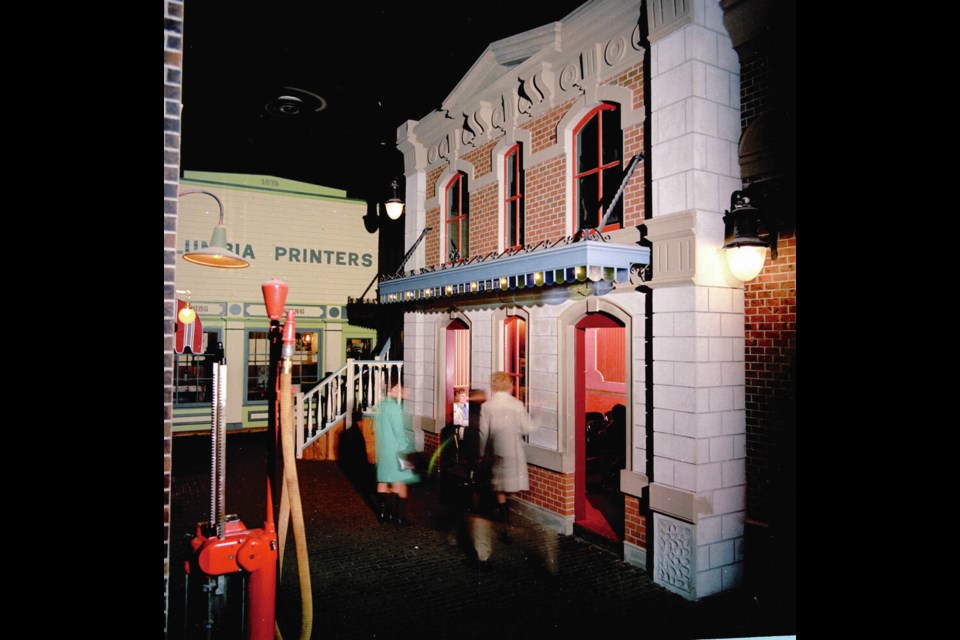

The gallery — later renamed Becoming British Columbia — contained Old Town, which replicated the wood-block streets of Victoria, along with Nanaimo’s Royal Hotel and a livery stable in Esquimalt during the late 1800s, among other structures.

The gallery also featured walk-through tours of the logging, mining, farming and fishing industries and a model of the bow of Capt. James Cook’s ship and a working gold rush waterwheel, where visitors could dip their pans for real gold.

“It set a standard for museums around the world,” said Erika Stenson, acting vice-president of museum operations, during a tour of the gallery.

The displays were designed to be interactive, allowing visitors to feel the floors change under their feet, hear the sounds of seagulls, lapping waters and passing trains — even smell the creosote of the docks or cinnamon in the pioneer kitchen.

“It was constructed to make learning about history fun,” said Stetson. “And it certainly held the test of time.”

On Dec. 31, nearly 50 years after it opened, the Old Town and industry exhibits will close for what the museum calls a “decolonization” of the displays. Artifacts ranging from a British officer’s sword to a heavy steel-wheeled wheat thresher will be removed, and the gallery will be dismantled down to the bare floors.

Included in the re-visioning process is the First People’s Gallery, as the museum consults with First Nations and “all voices of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½” to reset the narrative on how its presents British Columbia’s past.

It could take years.

Old Town

Creating the Becoming ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ galleries started years before the opening in 1972.

At the time, the museum had 200 to 300 employees and a talented crew of curators, exhibit designers, painters, carpenters and electricians. Other private contractors and professional artists also pooled their talents to bring the vision into reality.

Old Town was designed to explore ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s urban history, how wooden towns fuelled by the resource industry transitioned into brick, and how commercial centres grew as distribution and transportation points for people and commerce.

The original designers incorporated evolving occupations, from the blacksmiths of the horse economy to the age of the automobile; how coal, oil, gas and electric lighting arrived; changes in fashions and retail operations and how railways transformed everything with a flood of people and cheap goods.

Upstairs, a hotel bedroom depicts a slice of the lives of a colonial couple newly retired from Asia — top hat, knee-high boots and elaborate gowns are all on display while they wait for a new house to be built. Another room shows an importer’s office of the 1890s, and Columbia Printers holds two of the oldest manual presses in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½

Prototypes for each gallery were first built in detailed dollhouse-size multi-level models, a painstaking process that included many of the details and colours that came to life as actual floor construction began.

Carpenters, electricians, floor pavers and other trades worked simultaneously or in shifts, building two-level buildings along the woodblock street.

Larry Davidson was part of a Victoria paving company that installed some of the flooring in Old Town, and says it was a good group of people. “We had fun with that project. We used to go the Empress for some drinks when we finished at the end of the day.”

There were hitches along the way, however.

“They wanted a real [authentic] look to that street, but we knew the blocks were too tight the way they wanted,” recalled Davidson. “We came in the next few days and those blocks were all buckled, so we had to do it again.”

Davidson said he continues to visit the museum to show his grandchildren the floors he made. “I really hate to see it all go.”

The museum had its own painters and some contracted artists to do the detailed dioramas that gave many of the settings a 3-D lifelike look. Coloured lighting enhanced the paintings.

After carpenters completed curved-wood backgrounds, the artists moved in and painted scenes from photographs taken at the actual locations. The backdrop to the settler farm is from Dawson Creek, the gold rush painting is from Barkerville, and the fish cannery is from the 1891 Skeena Cannery near Prince Rupert.

Construction of the Gold Rush waterwheel and Capt. George Vancouver’s HMS Discovery were perhaps the most ambitious projects in the gallery. Each was built on site with big timbers, which took several months.

The waterwheel still functions 50 years later, recycling water through a sluice and back again. “It’s a testament to a good working design and to the carpenters at the time,” said Stenson.

The full-scale replica of the Discovery was built in place with heavy planks, surrounded by tarred pilings and dock ramps. The ship marks the first contact with Indigenous peoples at Yuquot, or Friendly Cove, in 1778.

Stenson said the details in the interactive displays can be credited to early curators and designers, many of whom have died or are now in their 80s and 90s.

The dark mine scenes with seams of coal were replicated from Cumberland and Nanaimo, and the mobile lumber mill to cut railway ties is from the Rocky Mountain Trench area in eastern ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½

Details were essential to make the displays as lifelike as possible, said Stenson.

Designers made mushy ground and manure out of lacquer-covered aggregate, and put in horse footprints before it dried; they installed a small hidden fan to blow a curtain in the pioneer kitchen, and added the clatter of a telegraph in the train station. One side of Old Town was fitted with gas-powered lights, the other with early electric lights.

Daniel Gallacher, curator of history with the museum in 1972, aptly described the gallery in a commemorative guide: “Indeed the success of any historical-setting approach to exhibits depends largely on the visitor’s powers of observation and imagination.

“For those seeking a wider historical interpretation, or in-depth detail on specific objects, there are information panels available. Yet, such aids are poor substitutes for a pair of sharp eyes and active mind.”

First Peoples Gallery

The First Peoples Gallery was opened in 1977, a visually stunning display of First Nations culture centred on Totem Hall’s monumental carvings from the Kwakwaka’wakw, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Gitxsan, Haida and Nuu-chah-nulth communities.

There are crest poles and house posts from Gwa’yasdams on Gilford Island, ‘Qélc (Old Bella Bella) on Campbell Island, Tallheo (Talio) on South Bentinck Arm, Xwamdasbe’ (Nahwitti) on Hope Island, Gitanyow on the Skeena River, hlragilda ‘llnagaay (Skidegate) and t’anuu ‘llnagaay (Tanu) on Haida Gwaii and Numnuquamis on the Sarita River in Barkley Sound.

When the gallery opened 44 years ago, First Nations works were classed as anthropological artifacts or examples of material culture rather than as art, the museum said. “Although First Nations languages do not have words for art in the sense of works intended only for decoration and contemplation, this exhibit uses the term in recognition of the exceptional esthetic qualities and superb workmanship of Northwest Coast carving of the past and today.”

Around the perimeter of the hall are examples of masks, regalia and modern works by Kwakwaka’wakw, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Haida, Tsimshian, Gitxsan, Nisga’a, Nuu-chah-nulth and Salish master carvers.

The Jonathan Hunt Ceremonial House is also a focal point, and is likely to remain as part of a redesigned third floor. It’s both a museum installation and a real ceremonial house for potlatch ceremonies, which were once outlawed.

It belongs to Chief Kwakwabalasami, the late Jonathan Hunt, a Kwakwaka‘wakw chief who was born and lived his life in Tsaxis (Fort Rupert) on the northeast coast of Vancouver Island.

An arrangement between Jonathan Hunt, his descendants and the Royal ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Museum allows the museum to exhibit the house permanently, while cultural ownership of the house and its images remains in the Hunt family.

Museum officials say it will be a monumental task to sort and catalogue the thousands of pieces in multiple displays in the First Peoples Gallery. And that will take consultations with dozens of First Nations groups, most from the coastal areas of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, who have objects there.

The process is aimed at correcting omissions and mistakes — a case in point is a mannequin of a Coast Salish chief that’s been on display for decades wearing regalia from five different nations.

The Great CleanOut

The third floor of the museum contains “hundreds of thousands” of artifacts, a fraction of the roughly seven million pieces in the museum’s entire collection, said Stenson. But it will be a tall task to remove them all from the floor as the museum starts “decanting” the artifacts from current displays.

The museum said it is still unsure how long that might take, or when the floor will reopen after consultations and an eventual redesign. Officials have already estimated up to five years, considering the consultation process and the time it will take to curate items into newly designed exhibits.

In the Becoming ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Gallery, the process has begun. The mining and lumber displays were closed off in early December, with museum curators in the process of removing items this past week.

Old Town will be taken down completely, said Dan Muzyka, acting chief executive of the Royal ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Museum, but elements of the layout — and some of the artifacts —will be preserved for new exhibits in the museum’s “new narrative.”

Muzyka said the sequencing of removals and any dismantling in Old Town hasn’t been finalized because the museum has to determine the integrity of the materials and whether they contain hazardous materials such as asbestos and lead paints. “We want it to be safe, first and foremost, for our staff,” he said. “Taking the displays apart presents a challenge as we consider the materials.”

The Discovery ship won’t likely be saved, considering the size and condition of the wood and paint, and other materials used in its construction.

Muzyka would not elaborate on what will happen to the artifacts as the deconstruction of the floor moves forward.

It’s likely many objects will be stored in government buildings and warehouses, since the new Royal ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Museum and Archives building slated for Colwood’s Royal Bay area won’t be ready for the museum to occupy until January 2025. Each item will have to be removed, checked for water or insect damage, catalogued and labelled — and then stored with appropriate temperature controls, special security or other specialized treatment. Items such as fabrics and paper are vulnerable.

“Some of these items have been there for 50 years, and require attention or even repairs,” said Muzyka.

Others are extremely valuable, like the “Turnagain” Nugget, the largest chunk of gold ever discovered in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, weighing in at 1,642 grams. It was discovered in northern ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ in 1937 when Alice Shea, out prospecting with her husband, saw something shining out of the corner of her eye and “turned again” to check it out.

Other items are going into travelling exhibits, with pop-ups in First Nations communities, shopping malls and vacant or government buildings across the province. The Indigenous Living Languages display at the entrance to the First Peoples Gallery is currently on the road in Smithers.

- - -

To comment on this article, email a letter to the editor: [email protected]