Here’s a peek behind the scenes at Coachwerks, the Victoria auto-restoration company that drew international attention last month after a Mercedes-Benz 300SL gullwing coupe sold for $4.5 million at an auction in Arizona.

That record price for a gullwing helped bring more attention to the restoration experts in Greater Victoria. This is, after all, where the car was lovingly restored.

Why is Coachwerks so successful?

“We are enthusiasts, driven by passion and dedicated to perfection,” says Dave Hargraves, one of the company’s managers.

The 300SL, one of the most sought-after vehicles among car collectors, is a specialty at Coachwerks.

Only 3,258 300SLs were built, including 1,400 gullwings from 1954 to 1957, and 1,858 roadsters from 1957 to 1964. Restored roadsters can sell for $1.75 million to $2.25 million US, while the coupes usually go for $2.25 million to $2.5 million US.

The coupes are known as gullwings because of the doors, which are hinged on the rooftop and open up instead of to the side.

A regular door would not have worked on the car because it used a tubular space frame chassis — the first production vehicle to do so. That innovation meant the door sill was far higher than on other vehicles, forcing the Mercedes engineers to innovate with the door as well.

Coachwerks is restoring another gullwing, along with six roadsters. It has worked on up to a dozen 300SLs at one time, including one of the most famous examples of the car in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

That was the 1960 roadster owned by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who got it from his father, Pierre. The car was made perfect here 20 years ago.

Along with the 300SLs, the shop has a wide variety of vehicles, including a Jaguar XK120 roadster racer, a Ferrari Daytona Spyder, several air-cooled Porsches, a Lamborghini Miura, a Maserati Ghibli, and a first-generation Mustang.

There is also the body of a two-seater BMW Isetta, ready to be shipped back to Dubai after Coachwerks worked on the body and paint, as well as a one-of-kind Ghibli, which was built to order by a businessman in Paris who helped Maserati survive a financial crisis. That car is in storage until the correct parts can be found.

Today’s Coachwerks has its roots in two local shops — Rudi Koniczek’s restoration shop in Saanich, and the original Coachwerks, a specialty auto body shop in Victoria that was owned by Mike and Tracy Grams.

The two companies worked together on more than 100 vehicles before being formally brought together as part of the GAIN group of companies in a 38,000-square-foot shop in Rock Bay. Today, Grams manages the body shop, and Hargraves, one of Koniczek’s former employees, runs the restoration side.

A typical restoration results in a car that is better than it was when it left the factory floor. Creating a work of art involves much more attention to detail than working on an assembly line, after all.

The people who bring their cars here don’t want to see flaws after spending $100,000 or $200,000 — or $850,000 if it’s a 300SL — for a restoration that might have taken a year or two. Everything needs to be correct, even the details that will be hidden when the car is finished.

When working on a 300SL, Coachwerks gathers information from original factory build sheets and other sources. Part numbers are checked to ensure that the right parts, not just similar ones, are being used. Finished cars will bear original Mercedes-Benz colours.

For every car that comes in, a job information book is created to record the results of an initial inspection, an estimate of the scope of the work, a parts list, invoices and more.

As much as possible is done in-house, including leather and upholstery work. It’s all recorded in the book, including notes on parts sent out – for rechroming, as an example – and when they were returned.

The book for the 1970 Maserati Ghibli in the shop this month shows that the body and paint work will cost $70,000 to $80,000, including 475 hours of labour and $10,000 in materials — and that’s just for the body work.

Parts from cars being restored are sorted and organized on shelves. A label on each rack of shelves includes information on the car, such as year, model and chassis number, to avoid mixup.

Before being reinstalled, those parts are refinished to look like new.

Owners of the cars being restored can keep track of the work through online photo galleries. The work is documented and made available to them, no matter where they are in the world.

“It’s better that way — we keep the customer involved in the process,” Hargraves says.

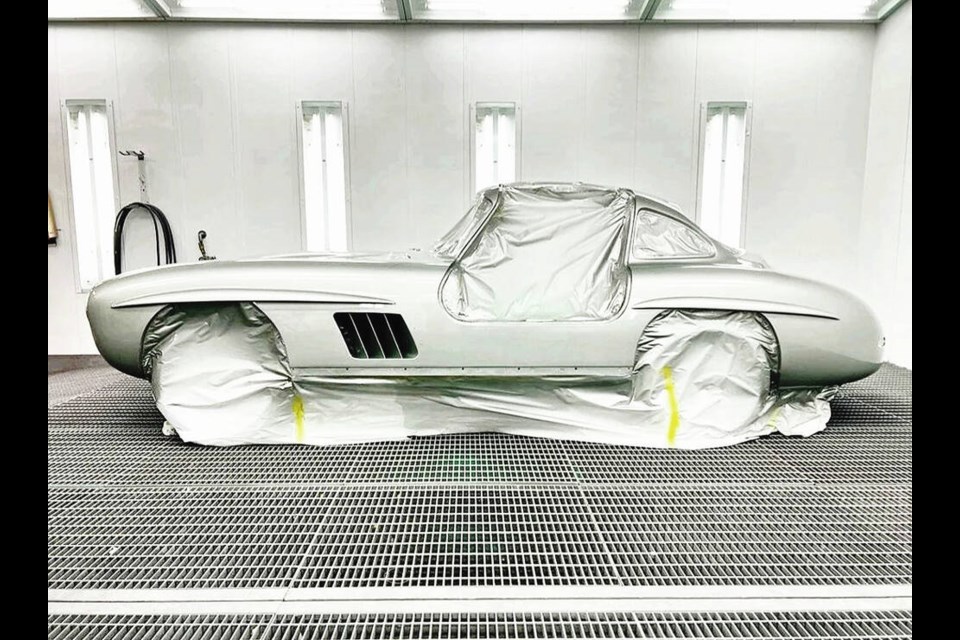

The gullwing in the shop is from Seattle, where it had been stored in a barn since a rollover accident in 1975. It was brought to Coachwerks in 2022 with a flattened roof and major body damage.

It might take two years, but by the time it is finished, the car will better than new.

At the time it was rolled, the cost of repairing the damage would have been much higher than the value of the car, so it was set aside. Today, with the value of a restored gullwing much higher, it makes financial sense to bring a seriously damaged vehicle back to life.

Besides, the kind of body work done in the 1970s would never make the grade today.

An example is a 300SL roadster, originally white, that was sent from Miami by its owner, who believed it was in fantastic shape. He wanted the car repainted anthracite grey.

Hargraves says that when the paint was removed, serious problems were revealed.

The car had been in at least one accident, with the dents fixed the old way. Holes were drilled into them, then a slide hammer was screwed in and used to pull the dents out.

If a dent was large, a body shop might have drilled and pulled a dozen or more small holes before using body filler to make the car look great again.

Standards are higher today, especially with cars worth more than a million dollars. It’s better to hammer the dent out, or make a new panel if the damage is severe.

Body filler might also have been used to hide rust holes and previous restoration failures.

One way to test the quality of a restoration is to check the thickness of the paint. This is done with a DeFelsko Positector, a magnetic induction gauge.

With a 300SL brought here from Venezuela, the body filler was so thick that the gauge did not give a reading. A previous restoration was simply not good enough.

With the paint removed, the amount of filler was obvious. There were major gaps between body panels, including one of almost an inch at the leading edge of the hood.

“Before, that car could have gone to a car show, to a Mercedes convention, to an auction. But now people can measure the thickness of the paint,” says Peter Trzewik, who runs the GAIN group.

That car was one of two 300SLs that were originally painted light blue. Both went to Venezuela.

“We need to do research to figure out who owned the car, who had the money to buy that kind of car in Venezuela at the time,” Trzewik says.

Sometimes, restoration deals with problems on cars that at first glance might seem close to perfect.

A case in point is a white 300SL roadster, which had a professional body and paint restoration a decade ago. The mechanical and suspension work was not done by a restoration shop.

Hargraves met the owner of the white car at a classic car rally last year in Bend, Oregon. On the road, the white car could not keep up with a car from Coachwerks.

The owner of the white car wanted to drive it, not just keep it for show, but driving it was not much fun. At 70 miles an hour, for example, it had a severe vibration.

After his frustrating experience in Oregon, the owner of the white roadster told Coachwerks to make it the best touring car possible.

Hargraves said the problem was that the white car was “not sorted,” meaning that there were problems underneath. But what were they?

The detective work started with swapping the car’s wheels and tires with a set known to be good. The problem did not go away, so the driveshaft was swapped for a good one. Again, the problem remained.

The axles were checked next, and it was determined that the axle flanges — basically, the parts that connect to the wheels — were bent. The permissible tolerance for axle run-out is 0.03 mm and these axles were at 0.4 mm.

That might seem like a trivial difference, but it caused the car’s driveability issues. Coachwerks had two used axles that were within the specified Mercedes-Benz tolerances and machined them to make them even better. These replaced the axles in the car.

To make the car more suitable for touring and rallies, the steering geometry will be adjusted and custom-built shock absorbers installed.

“By the time we are finished, it will drive like a completely different car,” Hargraves says.

The final bill for the work? About $20,000 — pocket change considering what the car is worth.

It would have been a more expensive repair, and possibly not as successful, without the extensive inventory of spare parts in stock at Coachwerks.

Mercedes-Benz was the first automaker to commit to keeping parts available for older vehicles. But that doesn’t mean that everything needed will be available through a factory order.

As a result, Coachwerks keeps its own supply of spares in an adjacent 8,000-square-foot building known as the “holding tank.”

“We never throw things away,” Hargraves says. “You never know when they will stop making certain parts.”

If parts needed are not available from local storage or the factory, new ones are made from scratch. The metal working room, with equipment that would cost $500,000 or more to replace — if you could find a source — is used to create new body panels.

Parts fabricated at Coachwerks are made to factory standards.

“We need authentic parts, and if we go to other suppliers, we cannot be sure that the parts are authentic and not cheap knockoffs,” Trzewik says.

Coachwerks has even duplicated the fitted luggage that was offered as an option when the 300SLs were new. (The cost? $12,000.)

In some cases, Coachwerks undertakes what Hargraves describes as “automotive archeology.”

One example is a 1970 Lamborghini Miura, which was shipped here by a frustrated owner after attempts at restoration by two other shops failed.

The car arrived in parts – 90 boxes in all. Each part had to be identified without having another Miura or Lamborghini diagrams to use for reference. Two hundred hours were set aside for that work.

If it was noted that a part was missing, the replacement cost had to be determined, assuming a replacement part could be found.

“It’s a painstaking process,” says Trzewik. “A mistake can be extremely costly.”

Not all restored vehicles will command stratospheric prices, and in some cases, the cost of restoration might exceed the value of the finished vehicle.

“A lot of the work that we do is for sentimental reasons,” Hargraves says, referring to people who have had a vehicle in the family for many years and want it returned to like-new condition.

In those cases, the value of the finished vehicle is considered in planning its restoration. That means the vehicle will not be made perfect in every way, something that can be done with a money-is-no-object 300SL.

“Still, we try to create a lot of bang for your buck,” Hargraves says.

Not everyone wants a complete restoration; sometimes, like with the Isetta, Coachwerks only handles the body and paint. At other times, a mechanical restoration is done.

Another specialty is the ability to authenticate cars. One tool used for that is a forensic kit typically used for firearms that makes it possible to determine if a car’s vehicle identification number has been altered.

The highest prices for 300SLs are for cars with matching numbers — in other words, cars with the engine, chassis and body they had when they left the factory. Given the dollars at stake, fraud can be an issue, so Coachwerks staff helps potential buyers around the world know they are getting the real thing.

Even with its 38,000 square feet of shop space, 8,000 square feet for storage, and an 8,000 square foot showroom, Coachwerks is looking to expand its operations.

The demand for the work done here is high, and the shop is known around the world.

“We don’t do a lot of marketing, so how do people from Florida find us?” Trzewik asks. “They don’t come here because we are cheaper.”

Building the team

It’s not easy to find employees with the rare combination of passion and ability that Coachwerks needs, given that some aspects of restoration are best described as a dying art.

“There is more and more demand, and fewer people who can do the work,” Dave Hargraves says.

An example, he says, is carburetor repair. Carburetors have not been found on new vehicles for at least three decades, so the number of people who can fix them is steadily declining.

Coachwerks’ 27 employees include people from Camosun College’s auto technician program as well as McPherson College in Kansas, which offers the most comprehensive restoration training program in North America.

“We are constantly advertising across ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and abroad searching for prospects that may be a good fit for our team,” says Hargraves.

One recent hire is Thomas Burchnall, who came to Coachwerks from England, where he worked for the Renault Formula One racing team.

Coachwerks sends staff members to Germany for training for two weeks a year, and trainers come to Victoria to offer even more training.

“It is hard to find people to do this type of work, so training is essential,” Hargraves says. “We grow our own talent.”