For most road-trippers, camping next to a swamp can be hell.

Swarms of mosquitoes buzz in a shadowy path around your head. They alight on your ears, neck and back. And in the space of a few seconds, their serrated mandibles tear into your skin, opening a path for six-needled mouths to plunge toward their goal — your blood. Then comes the itching.

But when dusk comes for Dan Peach, he’s the first to offer himself up as bait.

Last summer, the mosquito researcher spent months hunting for the notorious insect near the province’s bogs, lakes and rivers. On mountain tops, he caught furry mosquitoes; in coastal estuaries, he stalked tide pool dwellers, which can survive and reproduce in water triple the salt content of the ocean.

In one recent trip to Whistler, Peach said he ducked under bridges “like a troll” looking for hiding mosquitoes.

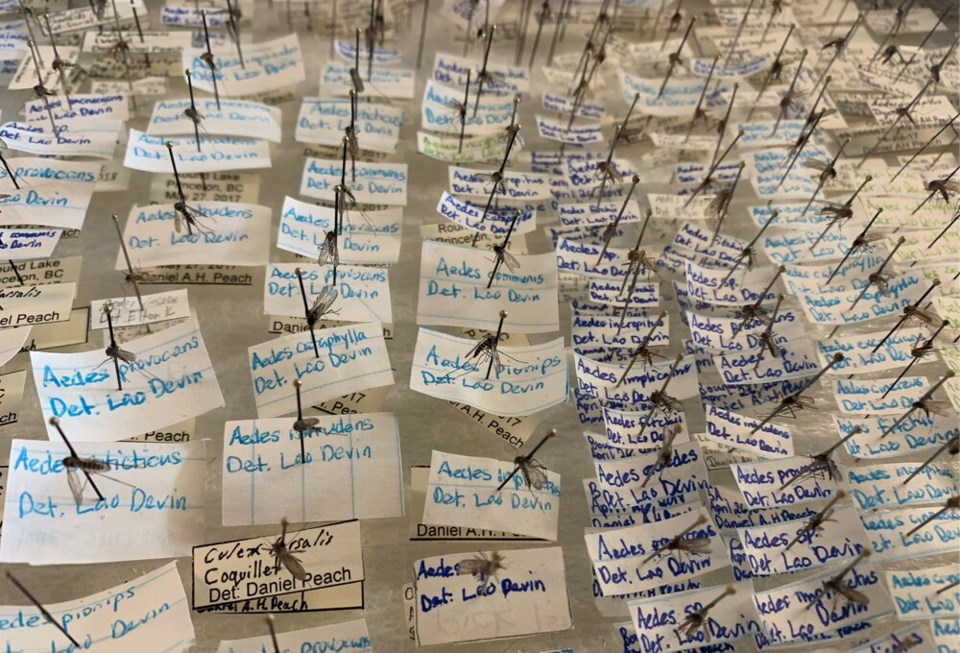

It’s all part of an ambitious mapping project that aims to uncover the range of the 51 mosquito species already known to exist in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½

From there, Peach will use the maps, combined with projected shifts in temperature and rainfall, to model how mosquitoes and the diseases they carry could spread on the back of a changing climate.

“We think these things have already been heading further north,” said Peach. “As climate changes and some of these conditions shift, where will they be in the future?”

But first, you need to catch them.

In his lab at the University of British Columbia, Peach pulls out an aspirator, what looks like an oversized turkey baster — only, instead of a bulb to suck in gravy drippings, he places the device to his lips and with a sharp inhalation, vacuums a mosquito into a filter inside.

Other mosquito-hunting devices are even less high-tech. To catch mosquito larvae he uses “a cup on a stick.”

“If they're floating in the water swimming around and they see a shadow or something, they'll dive down and hide,” he said. “So you get this cup on a stick and kind of lean in, like sneak up on them.”

At other times, the researcher will deploy a trap that looks like a foldable laundry basket with a lid and opening at the top. Black and white colouring attracts the insects, but so too does German-made synthetic sweat.

Peach opens a cooler door to pull out a half-opened package filled with a handful of chemicals, each a key ingredient in reproducing “stinky person smell.”

“It just kind of smells like gym socks,” he says holding it up to this reporter’s nose.

In the field, German artificial sweat gets dropped in the trap with carbon dioxide, an irresistible mix as artificially human as Peach can achieve.

But there are limits to what a single scientist — no matter how motivated — can do. In many small ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ towns, you can’t find carbon dioxide. And no matter how much Peach travels across the region, he can’t be everywhere at once.

Instead, Peach is hoping an army of citizen scientists will take up open palms to help him gauge the province’s ever-shifting mosquito population — one slap at a time.

“We’re calling it the ‘Ow! What just bit me?’ project,” said Peach, adding he also welcomes samples from Yukon. “Basically this summer, if you smack the mosquito, put it in an envelope and mail it to us.”

Add the date as well, plus the latitude and longitude of where it was killed (you can look that up on an application like Google Maps), he says. Once the lab receives the sample, they will grind it up and genetically sequence the remains to confirm the species. In return, Peach said he’ll email back information about what species of mosquito was slapped.

More than a window into what bit you, a slap and a trip to the post office offer residents of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and Yukon a hand in heading off future crises.

An unfathomable trail of bodies

It’s hard to overstate the risk mosquitoes pose to human health. By acting as a vector for everything from yellow and dengue fevers to malaria and Japanese encephalitis, the mosquito has killed humans at an almost unfathomable scale.

“Mosquitoes are the world's ,” said Peach.

Several researchers, including Peach, suspect malaria alone has . Or as Bill Gates put it in 2014, mosquitoes kill more people than people.

(At the time, mosquito-borne illnesses killed an estimated 725,000 people per year compared to 425,000 people who died at the hands of other humans.)

Since then, Gates and others have poured vast sums of money into , reducing mortality from the virus by 36 per cent between 2010 and 2020. But by the end of the decade, an estimated 627,000 still died from the disease. And at least 240 million more people are known to have suffered from the disease that year.

As one influential on the deadly trail left by the insects put it, “The mosquito remains the destroyer of worlds and the preeminent and globally distinguished killer of humankind.”

“Mosquitoes had this very profound influence on humans,” said Peach. “And since humanity has been a thing, basically, and they continue to do so today.”

“So there's a very real risk here. And sort of because of that, we focus on that area, and we don't really pay as much attention to the other things that mosquitoes do in an ecosystem.”

A dangerous vector heads north

Today, someone from Eastern ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ could be forgiven for thinking ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s Lower Mainland has always been a mosquito-free haven.

“Sixty years ago, before they diked along the Fraser [River] and drained Sumas Lake, the Lower Mainland was considered worse than the Prairies by settlers who had come through,” said Peach.

As recently as the 1960s, the province suffered under outbreaks of mosquito-borne Western Equine encephalitis, and a century ago, the Interior had instances of malaria.

“What's here now hasn't always been the case, and may not always be the case in the future. We need to kind of keep an eye on it,” said Peach.

One , for example, found the Aedes aegypti mosquito could spread into some parts of British Columbia under several global warming emissions scenarios. The mosquito species is vector for a number of pathogens dangerous to humans, including chikungunya, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, zika, West Nile and yellow fever viruses.

Across the planet, there are more than 3,500 mosquito species. About 80 of those are found in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½. But it’s not clear how the tiny creatures are moving.

Of the more than 50 mosquito species in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, a handful are known to be invasive — including the Northern House Mosquito (Culex pipiens), which carries the West Nile virus, and the Japanese rock pool mosquito (Aedes japonicus), a species which has been in the province for about a decade.

Often a forest-dwelling day-biter, the rock pool mosquito is known to carry a number of diseases, including the West Nile virus and two forms of encephalitis — infections of the brain that starts with swelling and headaches and can lead to vomiting, seizures, and in some cases, death.

But while ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is home to a number of mosquitoes known to spread disease, its climate is not yet ideal to allow some of the mosquito-borne vectors to follow.

That could change in the coming years, as warmer summers and wetter winters of many species northward, even across oceans.

“In the last a few years, we've been seeing some of the West Nile vectors in places farther north than they were before,” Peach said.

He points to Culex pipiens, which lately has turned up in Prince George.

“It was never thought to go that far north,” he said, noting the odd case in the southern Interior or Lower Mainland.

And while it's likely too cold up there for West Nile to spread in the wild, there’s a risk an infected person could bring the virus with them in a bird-human-bird spreading event transmitted through the bites of the invasive Culex pipiens.

Mosquitoes are only one-half of the picture.

“Climate is definitely limiting the spread of these pathogens,” said Peach. “You need it to be warm enough for long enough for them to spread.”

“There might be areas when there's nothing to worry about now, but perhaps, you know, 40 to 50 years in the future, we need to be concerned about pathogens like West Nile.”

A killer’s unsung role in sustaining life

Not all mosquitoes are pathogen-laden killing machines.

In fact, only female mosquito species take blood, and then only to develop their eggs. Many species don’t even target humans and only some carry pathogens that are dangerous to our health.

Mosquitoes are drawn to flowers as much as people. Adult mosquitoes feed on plant sugar, bouncing from flower to flower like a bee, in a process that appears to have been playing out since at least the , over 100 million years ago.

In an odd adaptation, mosquitoes take advantage of ants and their habit of farming aphids to collect honeydew.

As Peach put it in a recent article: “When a mosquito inserts its mouthparts into an ant’s mouth and strokes the ant’s head with its antennae, it tricks the ant into regurgitating and sharing its honeydew.”

They also act as a massive food source, a link driving the transfer of energy from aquatic environments — where their larva filter microbes, alga and dead leaves out of the water — to insect tissue, a key food source for fish, bats, birds, frogs, spiders, and predatory insects like dragonflies and beetles.

Those mosquitoes that don’t get eaten, often fall to the ground, where their biomass enriches the soil. An individual mosquito won’t add much, but in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and Russia’s north, huge swarms have led some researchers to estimate half of all migratory birds would if mosquitoes disappeared.

In Alaska alone, the biomass of mosquitoes has been calculated at over 43,500 tonnes — equivalent to .

In the Canadian Arctic, Peach says one researcher estimated how many bites he got on his arm in 10 minutes. Extrapolating out, he estimated standing naked among the Arctic mosquito swarm could leave a human dead from blood loss within two hours.

Closer to home, Peach says you’ll find huge swarms on British Columbia’s mountain slopes after a snow melt, or in valley bottoms after a flood.

“Nobody can agree on [the numbers],” said Peach. “But it's thought there are definitely more mosquitoes than there are stars in the sky.”

However much you hate mosquitoes, the science is clear, says Peach. Humanity must find a way to strike a balance — target and control those that spread disease, but don’t kill what for many of the world’s animal and plant species forms a foundation for life.

Anyone in British Columbia or Yukon interested in taking part in the citizen science ‘Ow! What just bit me?’ project is asked to:

- Record the date you squished the mosquito;

- Record the location using longitude and latitude (you can find this on apps like Google Maps on your phone or computer);

- Include an email address if they want a response about what species they found;

- Mail the information and mosquito to Dr. Dan Peach at:

Ben Matthews Lab

UBC Department of Zoology

4200-6270 University Blvd.

Vancouver, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½

V6T 1Z4

Stefan Labbé is a solutions journalist covering how people are responding to problems linked to climate change. Have a story idea? Get in touch. Email [email protected].

Video report by Alanna Kelly