NEW YORK, N.Y. - The seats were filling fast for a book reading last week by food personality Eddie Huang, and a Barnes & Noble employee came to address the crowd. Actually, it was to issue a disclaimer of sorts.

"We do not censor our guests here," said Maria Celis, a special-events co-ordinator. "If you're not comfortable with four-letter words or hip-hop references that may be over your head, this may not be your event. It's gonna be as freewheeling an event as we've ever hosted here."

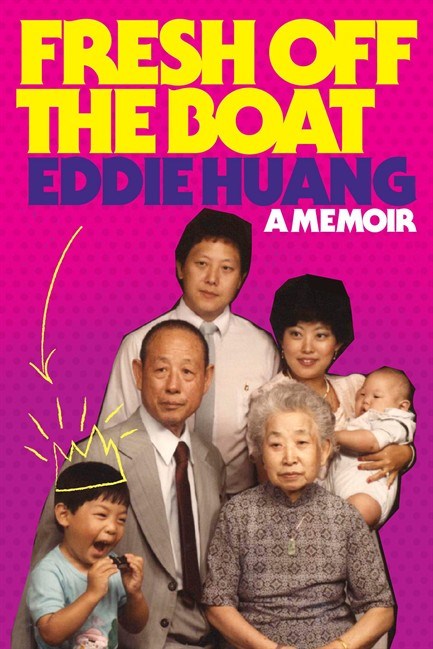

Clearly this wasn't your typical celebrity chef book reading, from Huang's prize-fighter-like entrance in a red-white-and-blue hoodie — "What up, New York?" — to the hip-hop music and cheers from a young, hip fan base, to the cheerful profanity, to the occasionally brutally honest subject matter — including childhood beatings meted out by his father. And the book, "Fresh Off the Boat," is hardly your typical celebrity chef's memoir.

In fact, let's get the "celebrity chef" label out of the way right now, because Huang doesn't like it at all.

Sure, he's gained some fame through his tiny restaurant, Baohaus, which first opened on the Lower East Side in 2009 ("bao" are stuffed, steamed buns), but he doesn't see himself as mainly a chef or restaurateur, he explains. Among other things, he's an author, a blogger, an essayist, the star and host of a Web series, a sometime standup comic, a streetwear aficionado, and also a food-world provocateur who's taken aim at successful chef-entrepreneurs like David Chang and Marcus Samuelsson, for starters.

"I abstain from defining myself," Huang, 30, says in a freewheeling interview the day before the book reading, perched on a stool at Baohaus as guests munch on dishes like the Chairman Bao, a bun stuffed with pork belly and crushed peanuts, or sweet bao fries — bread that's steamed, then fried, then glazed. "I don't like labels. I don't understand the need for them. When you define yourself a certain way, people have expectations."

"And I didn't come here," he adds, "to be a great chef. I came here to talk about culture. Food is just a part of it."

When Huang says he "came here," it's not an accidental turn of phrase. Though he was born in the Washington, D.C. area and raised mainly in Orlando, Fla., he speaks — and writes — through the prism of life as the son of Taiwanese immigrants. And though he seems quite fulfilled in his emerging role as a New York food personality, he makes clear he's still angry about what he endured, and what many immigrants endure in this country.

"This book is about being an outcast in America," he says. "I wanted to write it while I was still mad. Because, you get rich, you get fat, and you say, it was cool. You look back through rose-colored glasses. I didn't want to do that."

If you don't believe that there's still pain behind the smile, just ask Huang about life in the third grade.

Every day, the 8-year-old Huang brought in his mother's pungent Chinese food for lunch. He was ridiculed by other kids for his smelly lunchbox. Wanting desperately to fit in, he convinced his mother to buy him an American lunch.

"I was so excited at the grocery store," he says now. "I was going to be like THEM." But the next day, when he got to the front of the microwave line, waiting proudly with his chicken nuggets, a kid grabbed him by the shirt and wrestled him to the ground, using a vicious racial slur. Eddie fought back, physically, and he was the one who got sent to the principal.

"It was like, nothing you could do was good enough," he says now. "They get you to wear their clothes, eat their food ... And it's never good enough." At the restaurant, recounting the episode, he begins to choke up.

When Huang was still a youngster the family moved to Orlando, where his father managed steak and seafood restaurants. After a checkered academic career and getting into more than his share of trouble, Huang eventually graduated from Rollins College in Winter Park, Fla., and got a law degree at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law.

After being laid off from a law firm, less fruitful career attempts followed: selling sneakers and clothes, being a standup comic. Finally, he hit the restaurant business. Xiao Ye, which he opened in 2010, eventually failed, perhaps partly due to a scathing New York Times review in which critic Sam Sifton described Huang sitting at a table and texting with friends. "If Mr. Huang really wants to stand for delicious, he is going to need to work harder," Sifton wrote.

But the street food at Baohaus caught on, and in 2011 Huang moved it to a new location on 14th Street. He says he appreciated Sifton's review because it made him refocus attention on his food.

He's been less charitable about some fellow chefs. He's accused Chang, head of the growing Momofuku group of restaurants, as essentially a sellout. And he's had even sharper words for the very successful Samuelsson, the Ethiopian-born chef whose latest venture is the high-profile Red Rooster restaurant in Harlem. Huang (though he doesn't hail from Harlem either) finds both the place and the chef's memoir, "Yes Chef," inauthentic. To Samuelsson's description of Harlem in its glory days, Huang wrote in The Observer: "Thank you, Marcus, for that ride to the intersection of Stigma St. and Stereotype Blvd..."

Huang has even weighed in on the Tiger Mom author, Amy Chua. He responded to her book with an article on Salon.com, "In Defence of Chinese Dads," in which he argued that while his own Tiger Mom pushed him toward excellence, it was his dad's more relaxed, older-brother like approach that was essential — that in fact saved him.

But this same father is the subject of what many readers will find the most shocking element of his book. He describes a father who beat him frequently as punishment, chasing him with a whip, or even worse, a three-foot long rubber alligator with sharp scales. "There's something about crawling on the floor with your pops tracking you down by whip that grounds you as a human being," Huang writes. And yet he basically gives his dad a pass, citing cultural differences. "The bruises and puncture wounds ... were excessive, but I didn't think there was anything wrong with my dad hitting us," he writes.

This subject came up at the book reading, where a young woman rose and asked about the beatings. "This was the hardest part of the book — to shoot your parents in the face," Huang said. He described how authorities caught on while he was in school, and came to check him and his brother for bruises. The brothers never snitched, though.

"There were times I needed to be hit," Huang said to a suddenly hushed room. "I don't know if it is correct to say that it made me a stronger person."

At this point, chef Tom Colicchio, who was interviewing Huang at the reading, chimed in with his own story of being hit once as an older kid. "It is not good parenting," said Colicchio, famous for the Grammercy Tavern and Craft restaurants. "It's about losing control. It's a cycle that needs to stop."

Colicchio was full of praise for the honesty of Huang's memoir, and allowed that he has considered writing his own. "But I could never be as brutally honest as Eddie is, so I have to question whether I could ever write one," he told the crowd.

In an interview later, Colicchio marvels at the career Huang has created for himself at such a young age.

"He wanted a restaurant because that would give him a platform to spread his message, to get a voice," Colicchio says. "He wants to speak for Chinese-Americans. When you think about it — that he had this idea, and he's putting it all together and making it happen — it's amazing, really. This guy is really, really smart. Even if you don't like him, there's something there that you have to respect."

What comes next for Huang? Once the publicity blitz for his book dies down, he'll be back to his routine of writing during the day, keeping close tabs on Baohaus, taping his Web show one afternoon a week (and travelling for it two weeks per month), and dreaming up more plans. Like opening more Baohaus restaurants — but "not a chain," he says. "Each one will be different."

Huang loves living in New York, though he's clearly a downtown guy, scoffing at the stuffy Upper East Side. New York, Huang explains, is what the rest of America is supposed to be — but isn't.

"Here, I'm welcomed everywhere," he says. "But I'll never forget how people treated me before."