TORONTO - While ebooks have been exploding in popularity in recent years, scholars, chefs and those who just love to tool around in the kitchen say it's not time to stick a fork in the physical cookbook just yet.

"I'm a pretty messy cook, so having your computer on the counter is a recipe for disaster," said Ian Mosby, who is preparing to teach a University of Guelph course that encompasses the history of the cookbook.

"If I'm going to pay money to own something I would rather have the physicality of the book. I'm more likely to read a physical cookbook than an ebook."

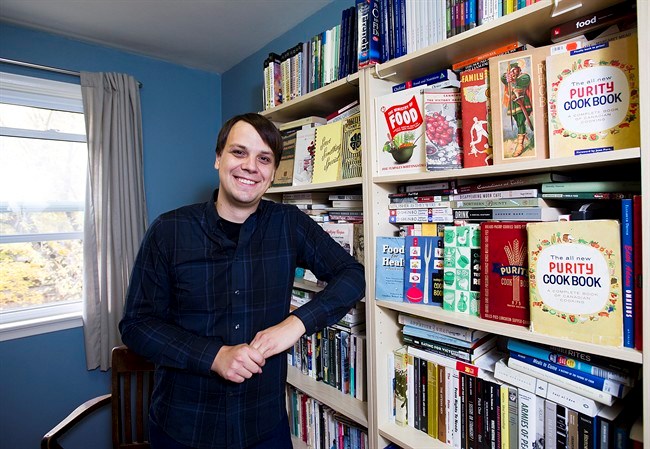

The university, which has a cookbook collection numbering around 4,000 volumes — including an impressive array of community cookbooks — offers plenty of material for his research, said Mosby, who owns almost 100 classic cookbooks and pamphlets (smaller cookbooks) related to his studies plus about 40 new editions.

Alison Fryer, owner of The Cookbook Store, says people have been downloading recipes from the Internet for years, but notes that new technology has created enhancements for "the cookbook experience."

Technology allows publishers "to produce the most gorgeous cookbooks. The digital photography now is stunning. The production quality is jaw-dropping of cookbooks even (compared to) five to 10 years ago. The other thing it allows them to do is create apps and enhancements and webisodes ... that go hand in hand with the book," she said from her downtown Toronto store, which opened about 30 years ago.

"If you've got in the fridge some chicken and broccoli and you just want to know what to make tonight, knock yourself out, go online and find something. That's probably the fastest way to do it," said Fryer, whose store offers cooking classes and author events and stocks some 9,000 titles.

"But if you want to sit down and read your cookbooks, as so many of us do, there's something about a living history that's in your hands and you turn the page with your hand and it's still so much a part of that."

Trend watcher Christine Couvelier, who recently passed the 3,000 mark in her cookbook collection, also thinks the print format isn't going anywhere, though she also enjoys such innovations as the video clips used with recipes and stories in publications like Martha Stewart Living that she reads on her iPad.

"There's something about experiencing a cookbook the way the author designed it so the right format is there," said the Victoria-based chef, who noted that some e-readers reformat cookbooks.

"But there's something tactile and inspirational and it transports me when I read a cookbook into that author's kitchen ... but when I then come back to my kitchen I'm still there with that person because I have that book with me. I just adore my cookbooks."

Mosby and a group of friends, all in their 30s, formed a cookbook discussion group about three years ago which encourages members to go beyond the realm of what they normally cook. Their meetings consist of a potluck dinner, using recipes from the book they've chosen to discuss that month.

Some members of Mosby's group purchase the electronic version, but he usually buys the actual book or borrows it from the library. He says he's not a big fan of e-cookbooks.

"It's definitely a different experience. Some of these books nowadays, they're beautiful," said Mosby, whose primary research interest is the politics, culture and science of food in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ during the 20th century.

"They're like pieces of art, so it seems worth it to spend the extra on getting the physical book."

Fryer noted that not everyone has a computer in the kitchen or the money to spend on a device. She acknowledges e-readers have their place, but "do you want to read a cookbook on a tablet that's 5-by-7?"

Many people swear by using recipes downloaded from blogs or websites, but a downside of online recipes is that they don't always work.

"People will look up a million recipes, but you have no idea as to the quality or the credibility of these recipes," said cookbook author and TV personality Christine Cushing.

"OK, someone has a blog and thinks they're an expert. That becomes the challenge. How do you know what you're getting is actually of a certain quality and somebody put a bit more time into it?" such as with a book.

"That is my pet peeve — people posting these crazy recipes that nothing works. Then it's very frustrating," she added.

With the number of cookbooks out there — Fryer estimates some 20,000 cookbooks are published annually in all languages, with about two-thirds of those in English, she says — many culinary authors must think it's lucrative enough to continue publishing.

Fryer points to last year's six-volume, 2,400-page "Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking" by Nathan Myhrvold, CEO and a founder of Intellectual Ventures, a firm dedicated to creating and investing in inventions, along with Chris Young and Maxime Bilet. Prior to that, Myhrvold was the first chief technology officer at Microsoft.

"So someone like that still feels that it's worthwhile to produce a physical hard copy," she said. "How do you argue with people like that who have (so many) R&D dollars ...that they can build their own cooking labs?"

Although some cookbooks are being published solely in an electronic format, celebrity chefs like Jamie Oliver and "Barefoot Contessa" Ina Garten continue to write and publish millions in hardcover. They also have an active online presence and use social media to reach out to their legions of fans.

And, some food bloggers are turning the tables and publishing their own hard copies. Recent examples are Deb Perelman's "The Smitten Kitchen Cookbook" (Appetite by Random House) and "What Katie Ate: Recipes and Other Bits and Pieces" by Australian Katie Quinn Davies (Studio).

"You can go online on your iPad and see (the blog) 'Smitten Kitchen' and then pick up the book and go in and cook in your kitchen. Kudos to people like Deb Perelman for doing that, making cooking accessible," Fryer said.

About a decade ago, the Cookbook Store started hosting on-stage interviews with cookbook authors, which have been hugely popular, Fryer said. Events have been held at Roy Thomson Hall and Massey Hall, as well as smaller venues. The publishers and the store benefit since the admission price includes the cookbook.

Sometimes it's the most unusual things that will take off, she said, citing 2010's "Quinoa 365: The Everyday Superfood" by sisters Patricia Green and Carolyn Hemming (Whitecap). Their followup book is this fall's "Quinoa Revolution" (Penguin).

"Who knew that something that people couldn't even pronounce (would sell) 300,000 copies or something and it spawned a whole new generation of quinoa and that spawned ingredient-driven cookbooks."

Sharon Hanna's "The Book of Kale: The Easy-to-Grow Superfood" (Harbour Publishing) did well last summer and books focusing solely on appliances like pressure cookers and slow cookers have become popular as well as books about food and culture like this fall's "Burma: Rivers of Flavor" (Random House) by Naomi Duguid, Fryer noted.

Mosby said he's noticed more cookbooks narrating a story, whether about a restaurant or a cuisine.

"The Art of Living According to Joe Beef: A Cookbook of Sorts" (Ten Speed Press, 2011) is "a wonderful cookbook, sort of a love letter to Montreal. It's interesting both as a book and as a cookbook," said Mosby.

"Similar is the 'Momofuku' cookbook (by David Chang and Peter Meehan, Clarkson Potter, 2009), which also tells a story about opening a restaurant and has thoughts behind (Chang's) philosophy of food."

The availability of online bookmaking programs has given rise to professional-looking volumes created by amateurs, be it church or school groups doing fundraising.

"I helped my mom put together a cookbook of recipes she made for us as kids," said Mosby. "It's kind of a historical artifact and also something we probably use more than any other cookbook."