It’s sunset, and I’m at the place to be in Granada — the breathtaking San Nicolás viewpoint overlooking the fortress of the Alhambra. Here, at the edge of the city’s exotic Moorish quarter, lovers, widows, and tourists jostle for the best view of the hill-capping, floodlit fortress, the last stronghold of the Moorish kingdom in Spain. For more than 700 years, Spain, the most Catholic of countries, lived under Muslim rule, until the Christians retook the land in 1492.

Today, Granada is a delightful mix of both its Muslim and Christian past. It has a Deep South feel — a relaxed vibe that seems typical of once-powerful places now past their prime. In the cool of the early evening, the community comes out and celebrates life on stately yet inviting plazas. Dogs wag their tails to the rhythm of modern hippies and street musicians.

Granada’s dominant attraction, the Alhambra, captures the region’s history of conquest and reconquest: its brute Alcazaba fort and tower, the elaborate Palacios Nazaries (where Washington Irving, much later, wrote Tales of the Alhambra), the refined gardens of the Generalife, and Charles V’s Palace, a Christian Renaissance heap built in a “So there!” gesture after the Reconquista. It’s what conquering civilizations do: build their palace atop their foe’s palace. The Alhambra is one of Europe’s top sights, but many tourists never get to see it because tickets sell out. Savvy travellers make an advance reservation.

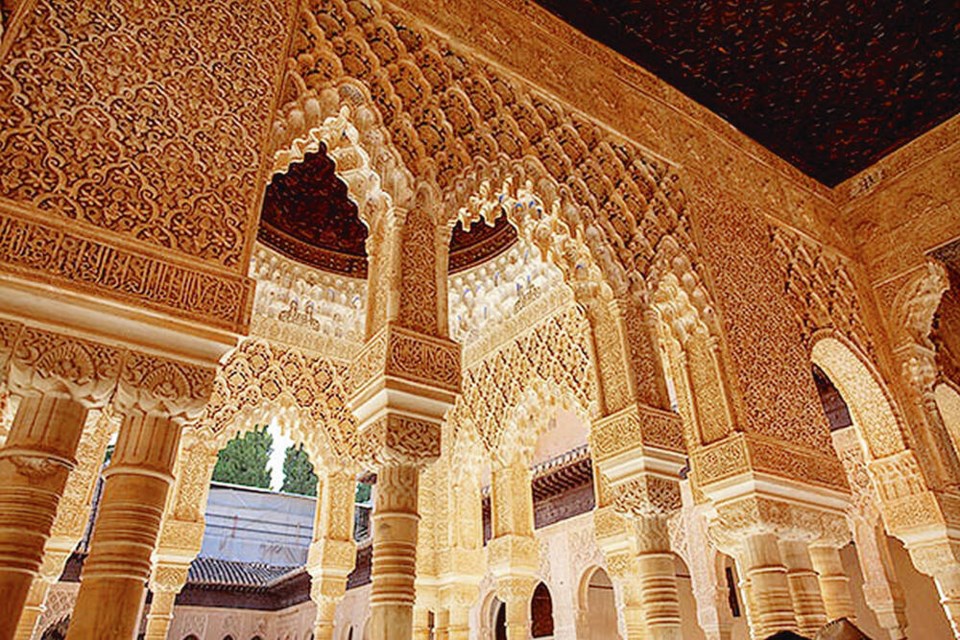

Moorish magnificence blossomed in the Alhambra. Their visual culture was exquisite, artfully combining design and aesthetics. Rooms are decorated from top to bottom with carved wooden ceilings, scalloped stucco, patterned ceramic tiles, filigree windows, and colours galore. And water, water everywhere. So rare and precious in most of the Islamic world, water was the purest symbol of life to the Moors. The Alhambra is decorated with water: standing still, cascading, masking secret conversations, and drip-dropping playfully.

Muslims avoid making images of living creatures — that’s God’s work. But Arabic calligraphy, mostly poems and verses of praise from the Quran, is everywhere. One phrase — “only God is victorious” — is repeated 9,000 times throughout the Alhambra.

When Christian forces re-established their rule here in 1492, their victory helped provide the foundation for Spain’s Golden Age. Within a generation, Spain’s king, Charles V, was the most powerful man in the world.

The city’s top Christian sight, the Royal Chapel, is the final resting place of Queen Isabel and King Ferdinand, who ruled during the final reconquest. When these two married, they combined their huge kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, founding what became modern Spain. And with this powerful new realm, Spanish royalty were able to finance many great explorers. It was in Granada that Columbus pitched his idea to Isabel and Ferdinand to finance a sea voyage to the “Orient.”

Granada’s former market, the Alcaicería, is near the chapel and was once filled with precious goods — salt, silver, spices, and silk. Protected within 10 fortified gates, it’s a tourist trap today, but this colourful mesh of shopping lanes and overpriced trinkets is still fun to explore.

The city’s old Moorish quarter, the hilly Albayzín, has cosy teahouses, flowery patios, and labyrinthine alleys where you can feel the Arab heritage that permeates so much of the region. There are about 2 million Muslims in Spain today, and Granada has a vital Muslim community. But Moors aren’t the only culture that has left its mark here.

Granada is home to about 50,000 Gypsies. (While called “Roma” people elsewhere, here they prefer “Gypsy.”) The Sacromonte hillside, at the edge of town, is the historic home to Granada’s Gypsy community. In the very caves that originally housed this community, musicians entertain tourists with guitar strumming and zambra dancing, similar to flamenco. For a fascinating look at traditional Gypsy life, visit the Cave Museum of Sacromonte: a series of whitewashed caves along a ridge, with spectacular views of the Alhambra and exhibits celebrating this rich and proud culture.

After visiting the Alhambra and then seeing a blind beggar, a Spanish poet wrote, “Give him a coin, woman, for there is nothing worse in this life than to be blind in Granada.” This city has much to see, yet reveals itself in unpredictable ways. It takes a poet to sort through and assemble the jumbled shards of Granada.

This article is used with the permission of Rick Steves’ Europe (www.ricksteves.com). Rick Steves writes European guidebooks, hosts travel shows on public TV and radio, and organizes European tours.