‘Prendi la donna,” I practised saying. “Basta, non farmi del male.”

Or, in English: Take the woman, just don’t hurt me.

You must admit, these smartphone translation apps are wonderful. Even in destinations far off the main tourist track, ones where English is relatively uncommon, they let you overcome linguistic barriers that might otherwise turn every interaction into a desperate game of Charades.

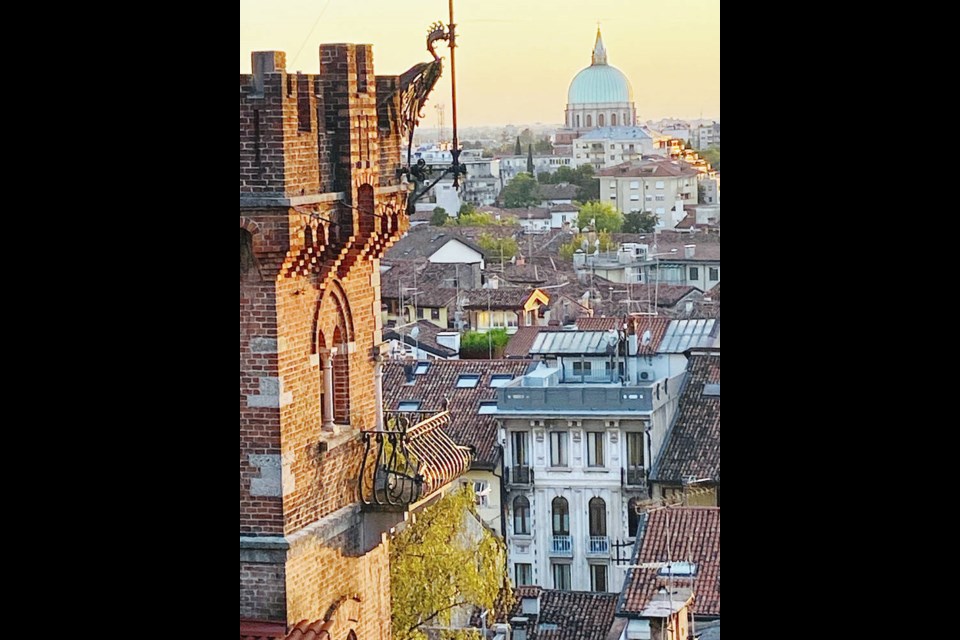

Udine is such a place. A city with a population half that of Greater Victoria, it nestles close to Austria and Slovenia in the northeastern corner of Italy — a back eddy, not the mainstream. Wander the cobbled streets of its centuries-old centre and what you mostly hear is Italian — or maybe the regional dialect, Friulian — not the Tower of Babel babble of those tourist towns where it feels as though the visitors outnumber the locals.

And that, dear reader, is part of the attraction.

Why did my wife and I choose to go to Udine? Because this is where her grandparents were raised before emigrating to ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ a century ago. Because my wife relished the idea of running a half-marathon along the same streets they once trod, with me cheering her on with roadside cries of “You look tired” and “Can’t you go faster? I’m getting bored.”

That was fun, but the great benefit was the discovery of a place that retains its everyday authenticity. Udine hits that elusive sweet spot: it feels like the historic, culturally rich, romantic Italy chased by so many visitors, yet it has yet to be overwhelmed by the visitors themselves.

This highlights an awkward dilemma for Italians and foreigners alike. The country has become a victim of its own popularity, swamped in places by a tsunami of visitors flooding the streets of Rome, swarming the cliffside villages of the Cinque Terre and threatening to further submerge poor Venice, which this year will restrict the size of tour groups and impose a 5€ (roughly $7.50 Cdn) entry fee on day-trippers.

Italy is at the point where one of the biggest complaints among tourists is how many damn tourists there are, all wrestling for the same slice of La Dolce Vita. If that sounds hypocritical (like the bumper stickers say: you’re not stuck in traffic, you are traffic) it also reflects how crowded it can get. (BTW, people get really fussy when you quite justifiably start throwing elbows in the cattle-car-cramped confines of the Vatican.)

Enter Udine, or at least places like it.

It’s not that Udine, the historic heart of the Friuli region, is untouristed. It’s just that it’s not overtouristed.

The city’s small, easily walkable core has the requisite attributes. Narrow streets. An ancient cathedral. To-die-for gelato. Cheap wine.

Expensive boutiques. Trattorias with Lady and the Tramp red-and-white checked tablecloths. Buildings that date back to long before Europeans set foot in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

Stylish, glamorous women stride the sidewalk as though it were a Milanese catwalk. The men, equally well turned out, all resemble a young Robert De Niro (really, it was like looking in a mirror).

What foreign visitors you do see are more likely to speak German than anything else. On a sunny day, they flock to the busy Piazza Matteotti as servers hustle between the tables of the outdoor restaurants ringing the square.

Nearby is the head-swimmingly historic (to a Canadian) Piazza della Libertà, where a 15th-century Venetian-Gothic town hall and the stately Loggia di San Giovanni stare at each other across the square. Elbowing each other for space are an imposing clock tower, a 16th-century fountain, a lion-topped column and statues dedicated to Justice, Peace, Hercules and Cacus, and, I think, Sir John. A Macdonald (just joking, Victoria!)

At the corner of the square are stairs leading up Udine’s only hill to the city’s 16th century castle, home to four fabulous little museums and art galleries. The four might not be as expansive as, say, Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, but neither are they as expensive, and you don’t have to time your arrival like a moon landing or crane your neck over two busloads of fellow gawkers to get a glimpse of The Birth of Venus. Standard admission to all four castle attractions is 8€ (as opposed to 25€ at the Uffizi) and we pretty much strolled in and had the joint to ourselves while contemplating paintings by Tiepolo, Caravaggio and Carpaccio, the latter of whom I confused with a sandwich meat.

But here’s the deal: As enriching as the historic/artsy city centre might be, for some of us the real rewards are found beyond the cobblestones. If you’re more fascinated by the mundane than the museums, venture beyond Udine’s core.

One of the benefits of staying in a B&B in an outlying residential area, as opposed to a hotel in the old city, is how quickly it exposes you to everyday Italy, to the way ordinary people live ordinary lives. The farther you get from downtown, the more Udine looks less like Ancient Rome and more like Modern Gordon Head — less glamour, more people who resemble your neighbours.

It was intriguing to see how Italian practices compared to ours — what they did better, or worse, or just differently. Frankly, when I travel I get a bigger kick out of perusing the local grocery store than the national gallery. (BTW, at our nearest Udine supermarket, prices were — with the exception of a 6€ bottle of Prosecco — similar to Vancouver Island’s. The cashiers were mostly middle-aged men, sitting, not standing, behind the counter. Thankfully, they didn’t yell at us when we forgot the part where you’re supposed to weigh, bag and print off a label for your produce before bringing it to the checkout.)

Just watching the flow of traffic — an unchoreographed but effective dance, with cars, buses, cyclists, pedestrians and scooters somehow weaving in and out of each other’s way with no one descending into us-vs-them transportation tribalism and feeling the need to fire off an indignant letter to the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ — is mesmerizing. Udine has very few bike lanes but a gazillion cyclists, most of whom appear to have forgotten their helmets and spandex at home. People of all ages ride in street clothes, including elderly women in elegant dresses. Buses to surrounding villages have seatbelts, which absolutely everyone ignores.

Some things there felt ridiculously familiar, like the music blasting out from a birthday party in a nearby home: Sweet City Woman, a 50-year-old song by a Canadian band, The Stampeders, shattering the Italian night, which amused those of us who weren’t trying to sleep before running a half-marathon.

Other experiences were just a bit different. Along with the half-marathon was a run-with-your-dog race where people and pooches stampeded down an 800-metre course through blocked-off streets. And never mind the 13th-century cathedral, it’s Udine’s 21st-century flushable porta-potties that will have Vancouver Island runners green with envy. Later in our trip, at a charity run for a children’s hospital near Milan, it was a surprise to discover the runner behind us smoking at the start line.

One Udine tradition it would be nice to emulate: the way people carve out social time in the late afternoon, gathering with friends or family in a local cafe for an after-work, after-school aperitivo — a bit of food and drink consumed a few hours before supper, which is typically a late-evening meal. The aperitivo is collegial, brings neighbours together, builds community — and reflects poorly on Canadians’ more solitary, rushed, drive-thru existence.

That too-busy-for-life rush, which some of us wave as proudly as a battle flag, is frowned upon in Udine. There, food is consumed while sitting at a table, as God intended. Espresso is sipped while standing in a cafe, but never while walking down the street. Swigging coffee out of a to-go cup on the sidewalk or cramming a croissant down your cakehole at a crosswalk is a fast way to brand yourself as a foreigner/barbarian.

Better to sit down at one of those corner cafes and engage the locals in translation-app-assisted conversation. This is the best part about language barriers: they’re a sign that you are talking to ordinary people who, unjaded by tourists, might be as curious about your life as you are about theirs. One evening, having encountered half a dozen old guys drinking 2€ glasses of wine outside a neighbourhood bar, we engaged them in a long, wide-ranging conversation — the cost of food, the lure of home, the sorry state of Udine’s soccer team, which can usually be found wallowing in the lower reaches of Italy’s top league, Serie A — despite none of us speaking the other’s language. (Long-ago high school French helped bridge the gap with one man who had lived in Quebec City, but he mostly talked about 1980s NFL football: “Earl Campbell, il était magnifique!”)

We had a lot of encounters like that: villagers eager to find family connections to my wife, a 16-year-old fretting about his driving lessons, a woman urging us to try frico, a potato, onion and Montasio cheese dish of which people in Friuli are proud. (You can buy T-shirts that read Make Frico, Not War.)

We liked Udine a lot. It was relaxed, real, cheaper than the better-known destinations and not really that far from anywhere. Pretty Cividale del Friuli, founded by Julius Caesar and on the UNESCO world heritage list, is only half a half-hour, 3€ train ride away. Trieste, where international flights land and a worthwhile destination in itself, is an hour away by rail.

The thing is, Italy is full of places like Udine, ones you might have never considered, and where the language barrier feels more like a gateway.