It was Adam Kurnicki, 11, who first spied the body of a strange-looking looking creature on the beach at Nels Bight at the tip of Vancouver Island.

The Vancouver boy was on a family-and-friends camping trip to Cape Scott when he strolled off to explore the shoreline on Aug. 1, only to be surprised by the remains of a menacing-looking fanged fish with a long, skinny body.

Adam called out, “Whoa Dad — check this out,” and the rest of the group joined him, father Alex Kurnicki said.

“All of us were like — that’s not a salmon.”

Adam looked at the huge eye cavities, speculating that it was probably a deep-sea fish, his father said.

The boy was right.

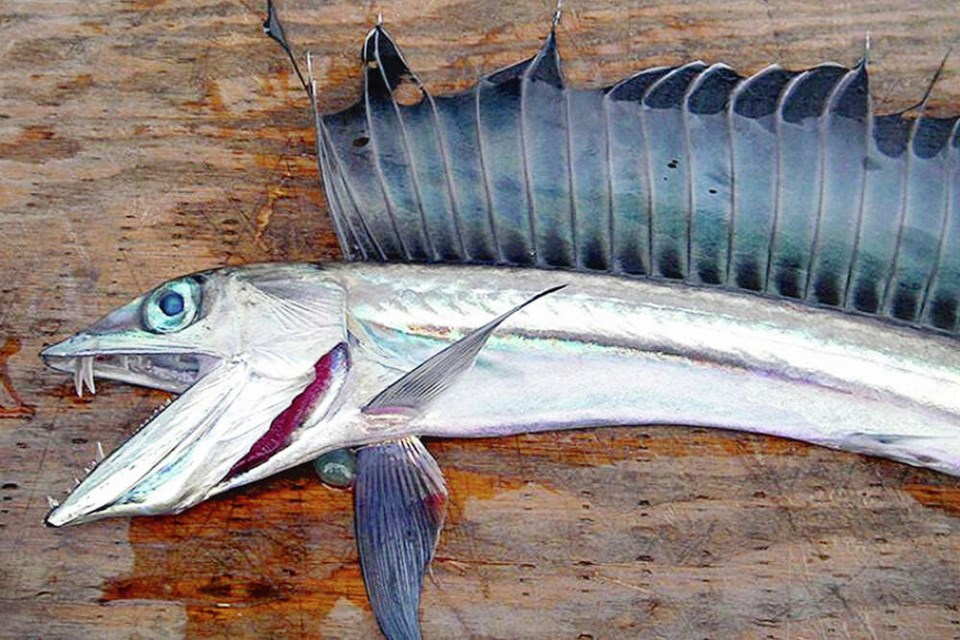

He had found the skeleton of an Alepisaurus ferox or long-nosed lancetfish, a that swims more than a mile below the surface, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

This one was about 1.2 metres long, Alex Kurnicki said. They can grow up to 2.1 metres.

Its unusual appearance had people guessing that it might be a barracuda, said Debbie Dymond of Nanaimo, who was part of the group. Later, when internet access was available, Dymond posted on social media to find out what they had found.

“It didn’t look like a salmon or anything I’m familiar with, and the things that are sort of in the centre of its mouth and pointing backwards were a little intimidating,” she said.

Although finding a big lancetfish is unusual for most of us, they wash up fairly regularly, said Gavin Hanke, curator of vertebrate zoology at the Royal ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Museum.

“We have no idea why, but perhaps they move near to surface waters at night to feed, and then the occasional one comes up too shallow, stays too late and gets dazzled by the morning sunlight.

“Their eyes are adapted to dark conditions, so bright light could be very disorienting.”

The museum has 25 lancetfish in its collection, Hanke said, adding he receives reports of one or two a year.

“They are large, and need to be put into vats of alcohol rather than in jars. I don’t collect them unless they are in absolutely pristine shape. Most wash up in a poor state.”

Museum specimens date as far back as 1896. They’ve been found in locations such as Sooke, Ross Bay, William Head, Pender Island and Esquimalt Lagoon.

“Some people think to contact a museum when they see odd specimens — others do not. So specimen acquisition can be hit and miss, and not a reflection of the species’ presence along the coast,” Hanke said.

Lancetfish are found as far north as the Aleutian Islands, he said.

They have a large sail along their back and do not have scales.

When such an unusual fish appears on our shores, it brings a reminder to all of us that many mysteries remain in the oceans.

Ben Frable, manager of the vertebrate collection at Scripps Institute for Oceanography in California, said there’s no good baseline for measuring the population.

A Russian professor worked with colleagues in the early 2000s to try to find out if there was any reason they are found on shore. “Because they show up on beaches all over the North Pacific, not just over here on this side, but over in Russia and Japan and Korea as well.”

The study found little correlation explaining why they are found, but the professor thought it might have something to do with large-scale oceanographic and atmospheric changes, he said.

It is known that lancetfish have a taste for salmon. “When they are out in the open ocean they will eat younger salmon, so they are part of the more northern food webs.”

Lancetfish are caught in high numbers as bycatch (non-targeted species) in some commercial fisheries, such as deep set longline for tuna and other fish, between California and Hawaii, Frable said.

For those who catch a lancetfish, “Unfortunately the meat, you can’t really do much with it.”

“A lot of deep sea fish tend to have a lot more water in their tissue than shallow-water species.”

When lancetfish is cooked, the meat shrinks dramatically and turns into a gooey, “sticky mess,” Frable said.

These are not muscular fish because they are not swimming constantly like a swordfish or a tuna. Collagen-like fibres run through their bodies that alter in texture when heated.

A chef once tried different techniques to see if the meat could be made palatable. But Frable, who tasted it, said it was unsuccessful, saying of the efforts, “Most them were very gross.”

He’s hoping that in coming years more research will be carried out on these unusual fish to find out basic facts such as how long they live and what they look like at maturity, and to learn more about their reproduction.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know, even through we are interacting with them a lot more.”

It is known that they tend to swallow prey whole and have a slow digestive system. This interests scientists studying that area of the ocean.

Their fierce-looking teeth are not used used for chewing food but for immobilization, Frable said.

Lancetfish use their teeth for either hooking something to pull it into their mouth more easily or possibly the teeth act as a cage to keep food inside the mouth, he said.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]