Imagine this: It’s April 1943. You’re a 21-year-old bomber pilot from Oak Bay on a cargo ship bound from Halifax to Liverpool.

Outside, the wind is howling, the blowing snow so thick that it’s impossible to see the other vessels in the convoy. Inside, you’re stretched out on your bunk, fully clothed, as dusk falls over the mid-Atlantic.

That’s when German submarine U-306 sticks two torpedoes into the hull of the Amerika.

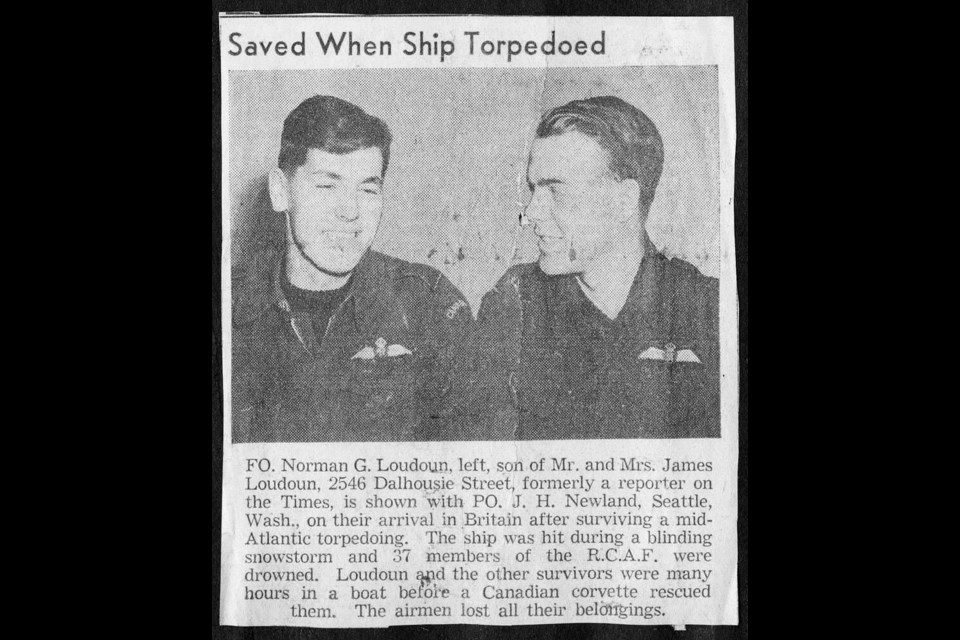

The Danish-built ship doesn’t go straight down. Norman Loudoun has time to scramble into his life jacket, hurry on deck, find a life raft. That doesn’t mean he’s safe, though. The blizzard is raging, the waves massive. The last man off the Amerika, its captain, slips while stepping into a lifeboat, has to be pulled from the water.

It takes a couple of hours for the Royal Navy corvette HMS Asphodel to get to the scene and begin plucking survivors from the heaving seas.

Most don’t make it. Of the 140 aboard the Amerika, 86 die, including all but 16 of the 53 RCAF men in Loudoun’s contingent.

The Vic High grad is one of the lucky ones, though. Even before joining the air battle in Europe, he emerges as a survivor of the war at sea.

It’s Battle of the Atlantic Sunday this week, a time to remember those who kept vital supply lines between ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and Britain open during the Second World War. It was a struggle that initially favoured the U-boats — almost 400 Allied ships were lost between January and July 1942 — but eventually tilted the other way, albeit at a cost.

“Most of the 2,000 Royal Canadian Navy officers and men who died during the war were killed during the Battle of the Atlantic, as were 752 members of the Royal Canadian Air Force,” says the Veterans Affairs website. More than 1,600 Merchant Navy sailors from ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ and Newfoundland were killed, too. There were also civilian casualties, including the 136 who perished when the ferry SS Caribou was sunk while crossing from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland in October 1942.

Loudoun’s escape from the Amerika, 79 years ago this week, was a near thing.

“I got into one of the free boats lying about and sat there with several other men until we were washed off by waves as the ship sank,” a newspaper story quoted him saying at the time.

‘The waves were enormous. The corvette’s skipper estimated they were 60 feet high. It was pretty tough in the boat and I don’t know how the corvette managed to take us aboard.”

Another story, this one in the Victoria Daily Times in November 1944, elaborated: “Although the bottom of the lifeboat was stove in, the survivors managed to keep it afloat for 3 1/2 hours in murky darkness until they were picked up by a British corvette and landed in Scotland.”

Loudoun might have got away with his life, but he lost everything else.

“He lost all his flying gear.” says his nephew, retired naval captain Kevin Carlé of Victoria. “He wrote his mother: ‘Hey Mum, can you send me a Cowichan sweater?’ ”

Back home on Dalhousie Street in Oak Bay, his mother did just that. Family photos show Loudoun wearing the garment under his uniform. Hardly regulation, but he didn’t care. It was warm and the skies were cold.

Loudoun eventually flew 38 missions in Halifax bombers. He finished the war as a squadron leader, winning the Distinguished Flying Cross for what the Victoria Daily Times, where Loudoun had been a reporter before enlisting in the RCAF in 1941, described as “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty.”

Loudoun told the newspaper that, compared with the sinking of the Amerika, the rest of his war was a “piece of cake.” But then he went on to describe one of his missions: “Returning from Brest one night, our port inner engine caught fire. I was obliged to ‘feather’ it, and in landing at our base with a full load of bombs I had not unloaded, I was unable to prevent the aircraft from swinging as I taxied down the runway. I overshot and ended up in the ditch. Fortunately, not a member of the crew was injured.” Some piece of cake.

After the war, Loudoun returned to Victoria, married Bonnie Rawlinson at St. Mary’s Anglican in Oak Bay, then departed for Alberta, where they had three kids and he spent a long career in the oil patch. He died in Calgary in 2012. Great guy, great public speaker, good artist, his nephew Carlé says.

“Like many of these people, he didn’t talk much about the war.”

Loudoun did eventually open up about his ordeal at sea to Carlé, another military man, though. The details were pretty awful, but his uncle described them all matter of factly. “He said: ‘I was a young guy. We took it in stride.’ ”

Not that it was actually that easy. Loudoun’s experiences stayed with him, Carlé says. “He suffered.”

Of course he did. Think of what they all went through in the cold and the dark, and the heaving seas.

There’ll be a public Battle of the Atlantic ceremony by the legislature this Sunday, May 1, from 10:45 until noon.