A ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝ driving test could discriminate against people with mild dementia who may be safe drivers, says a North Vancouver man whose mother-in-law recently gave up her driver’s licence, and with it, some of her independence, to avoid the assessment.

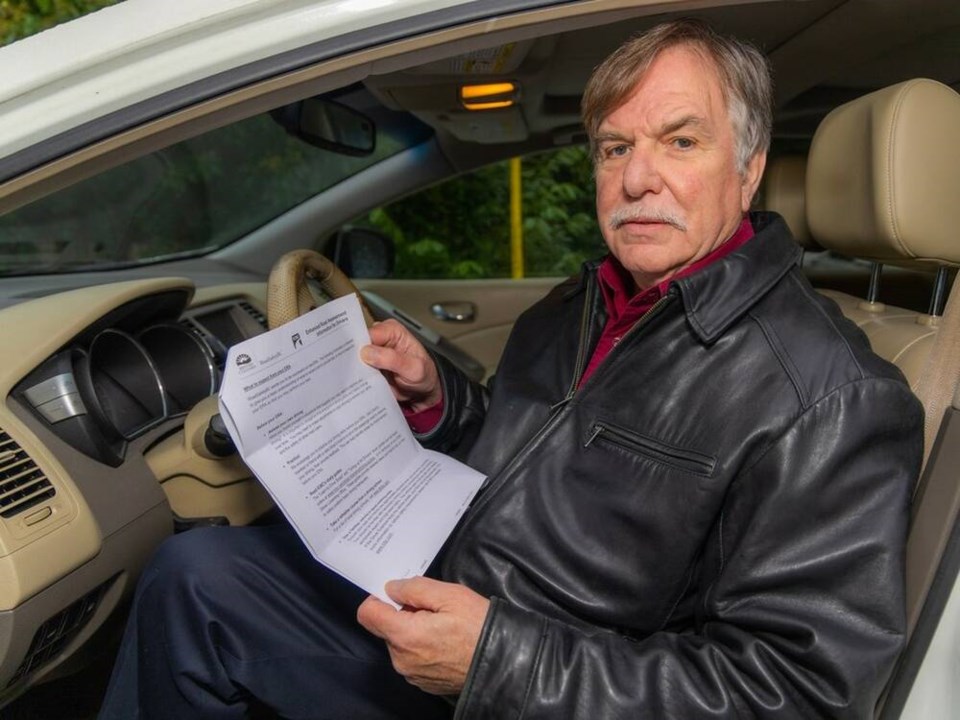

Damian Dunne said his wife’s 82-year-old mother is “a bit forgetful” and sometimes repeats questions, but her grasp of the rules of the road remains strong. In October, after learning she was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, she received a letter from RoadSafety ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝ requiring her to complete an enhanced road assessment to keep her licence.

Some aspects of the test would be challenging for someone without dementia to complete, said Dunne. “I was quite shocked.”

The family’s situation highlights the complexities around road safety and dementia, which affects more than 500,000 Canadians today, according to the Alzheimer Society of ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝, with the number expected to rise to 912,000 by 2030. While road assessments are intended to keep both the driver and public safe by testing a driver’s “functional ability to drive,” dementia is progressive and affects people in different ways.

The Alzheimer Society of ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝ said people who have been diagnosed with the early signs of dementia often find the test notification “jarring.”

“A big part of what we do is help families talk through the complexities of dementia and driving,” said Amelia Gillies, a support and education co-ordinator.

Dunne said many aspects of the 90-minute road test seemed reasonable and designed to ensure safety, but he questioned a requirement to remember and follow a three-step driving instruction — such as “turn right at the next intersection, then turn left at the traffic light, and then left at the stop light — and a test where the driver is directed to a certain point, then must turn around and follow the exact same route back to the start.

“When I’ve told other people about it, several have said they wouldn’t be able to do that,” Dunne said.

Determined to maintain some independence, his mother-in-law, who lives in Chilliwack, booked her test. But when she got to the testing location, she began crying and surrendered her licence instead of taking the test.

Dunne said he understands the need for safety, but no one has explained to him why following multi-step directions and driving a route in reverse is a requirement. His mother-in-law uses Google Maps and the family can see her location using a GPS tracking app.

“This has taken away her independence to shop, go to church, drive to appointments and visit friends,” he wrote in a letter to Mike Farnworth, ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝’s public safety minister.

Gillies said dementia impacts different areas of the brain at different times for different people, so while some people can safely drive for months or a year after being diagnosed with dementia, others might struggle.

“We sometimes say if you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia, and that translates to driving too,” she said.

Gillies said some doctors will refer people for a road test immediately, while others do not. As a result, the society hears concerns from people, like Dunne, who are surprised by the test, but also from families who are concerned about a family member who is still driving when it may be unsafe.

Way-finding is one of several issues that might arise for someone driving with dementia, she said. More significantly, dementia can affect visual processing, as the brain struggles to quickly interpret information coming at it and then react appropriately.

The enhanced road assessment is not a pass or fail test. According to the government policy, it consists of tasks designed to “assess driving skills and behaviours in situations of increasing complexity, yet within the abilities of a healthy, experienced driver.”

After referral, drivers are typically given 60 days to take the test, which is free. Their licence is cancelled if the test is not completed.

The test results are considered along with other information, including driving record, to determine whether a driver is “medically fit and functionally able” to safely drive. The driver may keep their licence, have restrictions added to it, or have it cancelled. RoadSafety ÎÚŃ»´«Ă˝ may schedule a reassessment for a later date, with the interval based on the driver’s medical condition.

In a statement, the Ministry of Public Safety said the assessment program has been in place since 2018. Between 2018 and 2021, an average of 4,680 people have been referred each year.

Of all medical fitness cases involving an assessment, 20 per cent of drivers are found medically unfit to drive, while 30 per cent either surrender their licence or have it cancelled when they don’t respond.

Drivers may request a review of a decision if they feel it is unfair.