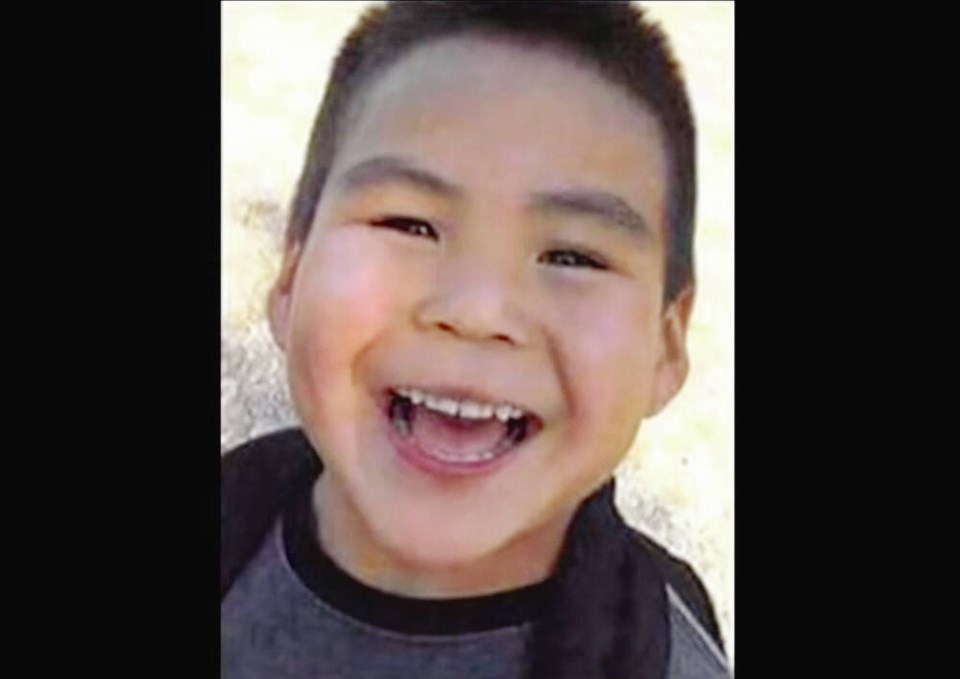

Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω’s child advocate says the death of a six-year-old Indigenous boy in Port Alberni six years ago continues to affect the decisions her office makes.

“It’s been ongoing for my whole term,” Representative for Children and Youth Jennifer Charlesworth said Thursday. “He is in my mind and where certain doors are closed, I try and figure out where are the open doors so we can bring these kind of issues forward.”

Dontay Patrick Lucas died on March 13, 2018, of blunt-force trauma to the brain after being returned to the care of his mother by USMA Nuu-chah-nulth family and child services.

His mother, Rykel Charleson, and stepfather, Mitchell Frank, deprived the boy of water, food and sleep, hit him, bit him and forced him to hang by his knees from the top of a door until he fell.

The couple, who were originally charged with first-degree murder, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and are to be sentenced in Port Alberni in May.

Jody Bauche, a former Representative for Children and Youth investigative analyst responsible for the comprehensive review of Dontay’s death, told the Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω that the representative should conduct a full investigation into Dontay’s death. She also said she pushed the representative to have meetings with the community and with USMA to share her findings from the comprehensive review to support a healing process, but nothing was done.

Charlesworth said information provided by Bauche is “inaccurate.”

“At the end of a comprehensive review, there is a recommended disposition given by the analyst and the recommended disposition was done in complete adherence to what the analyst recommended. And we’ve got records to that effect,” said Charlesworth.

Her office is still unable to investigate Dontay’s death because of the ongoing criminal investigation, which will only end after the accused are sentenced and the appeal period is over, she said.

“I don’t want anyone to think that our office doesn’t pay really close attention and care to things that are deeply, deeply tragic. Of course we have to pay attention to them and we did exactly what was recommended.”

Dontay’s story has illuminated the systemic issues that need to be addressed during a transition that will give First Nations complete control over the care of their children, said Charlesworth.

Children have a right to be close to family and have a connection to their culture, said Charlesworth, but they have a right to safety, too.

“I sometimes do worry about that because these are complex situations, especially when there are intergenerational trauma issues,” she said.

Charlesworth said she understands that Dontay’s family, former foster parents and others in the community have unanswered questions about the boy’s death, but legislative provisions prohibit disclosing personal information.

“It’s very hard when you’re out in the community and you’re providing the care and you love these kids and you get to know them … I find myself chafing at the inability I have to tell the full story in many cases. There is some information I can’t share even in a public report.”

This week, Charlesworth told the Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω in a statement that she made the decision to not conduct a full investigation into the child’s life and death due to a number of factors, including the potential further harm and trauma it could cause the family and community, and the amount of time that had passed since his death and how that might affect the quality of the investigation.

Asked again if she was considering a full investigation, Charlesworth said she is “always kind of reviewing.”

Dontay’s case was on the agenda at her office last week and was discussed Thursday at her quarterly review, she said.

“My question is: Can I do something meaningful for this little boy and what’s happened to him to prevent further harms being caused to children in situation like this in another way?”

Dontay’s story will likely be woven into the office’s review of child well-being and supports in Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω that will be released in June, she said.