Victoria’s crime severity index number rose last year, but much of that was due to an increase in reports of non-violent crimes, since the index number for violent crime was down more than nine per cent from the previous year.

And at least one expert says that increase in non-violent crime reports is in part due to changes in police reporting practices.

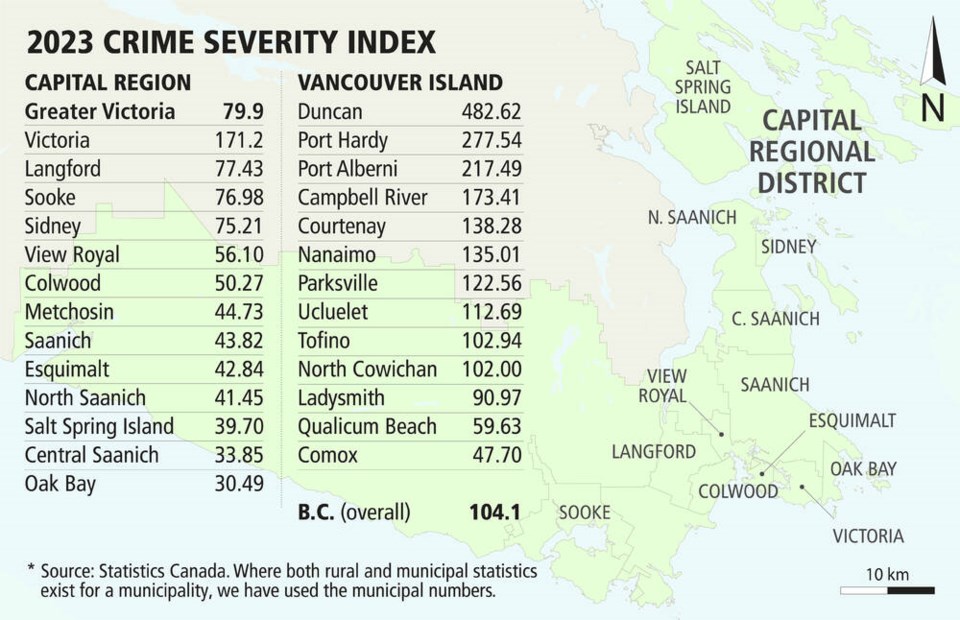

Statistics ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ data released last week show Victoria’s crime severity index number was 171 in 2023, up from 157 in the previous year. Greater Victoria as a whole had an overall index number of 80, below the provincial average of 104.

The index, which measures the volume and severity of police-reported crime, is meant to be a more meaningful interpretation of statistics, as it weighs the severity of crimes reported, rather than simply the crime rate, which can be skewed by the number of petty crimes.

Victoria’s index number of 171 in 2023 was higher than it had been in a decade, but still below its crime severity index numbers from 1998 to 2008.

While the severity index for violent crime in Victoria dropped 9.4 per cent from 2022, coming in at 146 for 2023, the non-violent crime severity index for Victoria was 182, a high that hasn’t been seen since 2008.

It also increased just over 19 per cent between 2022 and 2023.

Simon Fraser University criminology associate professor Bryan Kinney said the increase comes at a time when reporting and tracking of non-violent crimes is increasing.

Kinney said much of the growth that he’s seeing in the crime severity index comes from reports of intimate-partner violence, harassment and fraud — crimes that weren’t being reported or tracked as frequently in the past, particularly those that involve some form of online victimization.

“Police are getting better at knowing what they didn’t know five, 10 years ago.”

The crime severity index should not be used to judge how serious crime problems are in an area but how well police are able to keep track of what’s happening in their communities, he said.

In 2017, police forces began including unfounded cases — incidents reported to police that could not merit or sustain an investigation — into their crime reporting data, Kinney said.

“Lowering the bar for inclusion into the data, it means that you’re going to catch more of the less-serious stuff,” he said. “It might give us a few bumps and upticks that are kind of unwelcome in some communities, but I think that will even out.”

Langford’s index number of 77 in 2023 was higher than it had been in a decade, primarily fuelled by a non-violent crime severity index increase of more than 47 per cent, from 55 to 82, in one year.

The violent crime severity index in Langford declined by 2.54 per cent in the same period.

In Nanaimo, with an index number of 135 overall, there was a less than one per cent increase in the non-violent crime severity index and an almost eight per cent decrease in the violent crime severity index.

Kinney said it’s more useful to look at the crime severity index as a year-to-year comparison, though he cautioned that the numbers for municipalities with smaller populations are particularly vulnerable to being skewed by one or two crime sprees.

“If someone is persistent and really engaged in breaking and entering, they can do 30 break-and-enters in a couple of weeks and really mess with your data,” he said.

Duncan recorded a severity index number of 482 in 2023, up from 230 in 2022.

The city of about 5,000 is the primary urban centre in the Cowichan Valley and is policed by an RCMP detachment that serves Duncan, North Cowichan and the rest of the valley.

Kinney said the fact that Victoria’s overall crime severity index number is higher than for its neighbours comes as no surprise, given that the city is a hub for many events, industries and services.

“It’s a major centre. It’s going to have some of these somewhat persistent big city problems.”

Victoria’s police department has long pointed to the city’s high crime severity index as a reason to merge police forces in the region.

In a statement, VicPD said it has long supported amalgamation with other departments in the region to “unify the resources needed to resolve the ongoing reality of public safety in the region.”

A number of policing resources are already shared across the capital region, such as officers working in the road safety, domestic violence and major crimes units.

Saanich and Victoria police departments have an integrated canine unit and the Greater Victoria Emergency Response Team, or GVERT, draws on officers from five municipalities in the region.

Kinney said while amalgamation may increase the efficiency of “standard daily police work,” police responses to serious events would likely still be the same.

“However it’s organized, I don’t see it being terribly different, as far as the public would feel,” he said. “You probably would have the same policing professionals.”

Victoria Police Chief Del Manak said the index numbers show that Victoria has more social disorder concerns and a population with “higher needs” than its neighbour municipalities.

When it comes to reducing crime, police are only one part of the puzzle, Manak said. “We must continue to work together with our community partners and all levels of government to reduce Victoria’s Crime Severity Index,” he said in a statement.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]