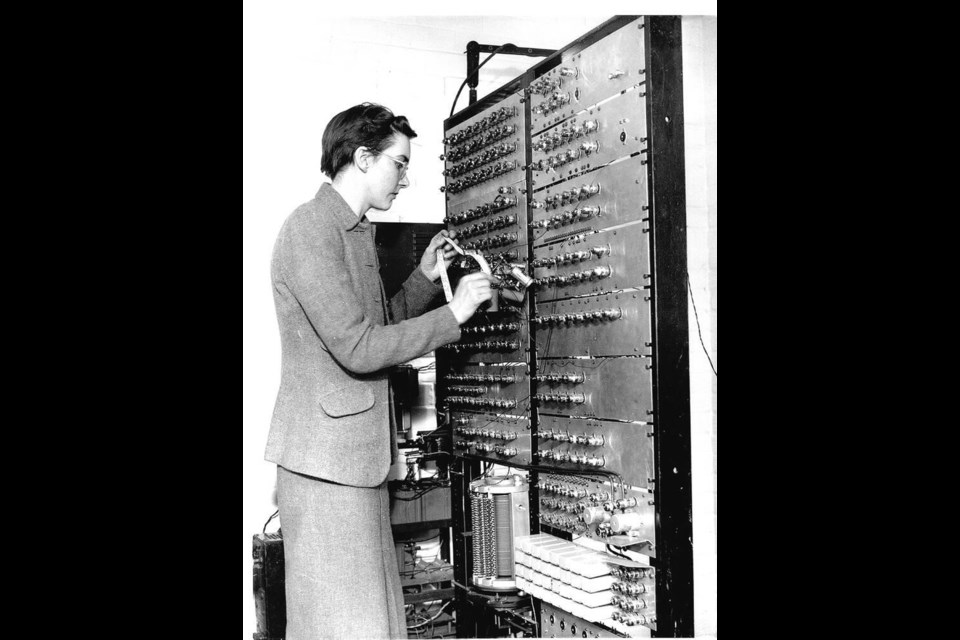

Kathleen Booth was a computer pioneer.

Indeed, her work was so significant that when the 100-year-old died this fall, her passing merited major media coverage in her native Britain: the BBC, the Telegraph and the Times, which ran a full-page piece cataloguing her achievements.

So why, then, didn’t we all know that she had spent the past 44 years living in Sooke?

“She was very humble,” says her daughter Amanda Booth, by way of explanation. “She was not one to blow her own horn. She would tell you she did nothing of significance.”

There’s more to it than that, though. We often learn, after they’re gone, of people who quietly settle on Vancouver Island later in life after doing extraordinary things elsewhere.

In Booth’s case, elsewhere was England, where the Telegraph described how she “co-designed one of the world’s first operational computers and wrote two of the earliest books on computer design and programming; she was also credited with the invention of the first ‘assembly language.’ ”

The latter did away with the tedious work of rewiring cables and changing switches when reprogramming computers.

The Times began its piece this way: “On November 11, 1955 Kathleen Booth typed some French words into a computer: ‘C’est un exemple d’une traduction fait par la machine à calculer installée au laboratoire de Calcul de Birkbeck College, Londres.’ Out came the English equivalent: ‘This is an example of a translation made by the machine for calculation installed at the laboratory of computation of Birkbeck College, London.’

“It was probably the first public demonstration of what today we call a translation app, and an early use of artificial intelligence to tackle the challenge of interpreting idiomatic nuances between languages.

“By then Booth had long been a pioneer in the field of computer science. She had started as a research assistant to her future husband, Andrew Booth. Together they developed the Booth multiplier, a highly complex algorithm that she once jokingly dismissed as an ‘arithmetical routine devised over egg and chips in the ABC tea shop in Southampton Row.’ ”

The story went on, in detail challenging to those of us who are still trying to figure out how to change our oven clocks after Sunday’s time change, to describe a dizzying array of accomplishments.

It all makes for a fascinating tale. Born Kathleen Britten in Worcestershire in 1922, she earned a math degree before working on aerodynamics at the Royal Aircraft Establishment during the Second World War.

“She used to say that, in an odd way, the war did her a favour,” her daughter says: It opened science-based jobs to women who had previously been limited to teaching.

It also helped that Andrew, whom Kathleen would marry in 1950 — the same year she earned her PhD — was broad-minded when it came to gender barriers. The Times wrote that the work the couple did together at Birkbeck College “created the foundations for what is now known as computer science.”

In 1962, unhappy after Andrew was passed over for a Birkbeck College department head’s job, the Booths moved to the University of Saskatchewan, where he was dean of engineering and she an associate professor. A decade later. they moved to Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont.

She also continued her work on automated translation — an important endeavour in a bilingual country such as ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½. (The translation work also had a side benefit for Amanda, now well-known in Sooke as a veterinarian, and her brother Ian, a Victoria-area physicist, when they were home-schooled as children: “Our French teachers were always her grad students,” Amanda says.)

In 1970, the Booths bought a summer property just east of Sooke on the water at Cooper’s Cove. It would become their full-time home in 1978.

On the Island, the Booths launched a computer consulting business, Autonetics. Clients included the Institute of Ocean Sciences, where they modelled how ship noise would affect marine mammals, and Royal Roads Military College, where she was associated with research that remains hush-hush.

Booth continued to employ her expertise as she aged. At a time when such things weren’t readily available, she wrote the software package for Amanda’s veterinary practice. “How many 70-year-old mums would be able to do that?” Amanda asks.

At home, Booth was a great grower of both vegetables and exotic plants, taking an active role in Sooke’s gardening club.

She was a great explorer of the outdoors, too. When Amanda and Ian were of elementary-school age, she would take them bushwhacking to distant beaches or rattling down remote logging roads. “My dad would be muttering and swearing that she was wrecking the car.”

Booth was an avid hiker until 15 years ago, when mobility issues began to slow her.

Kathleen Booth died Sept. 29, 13 years after her husband. That so few of us knew her story was a reminder of how many extraordinary people are in our midst, and how self-effacing they often are.

“I think we have more than our fair share of people like that on the Island,” Amanda says. Lucky us.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]