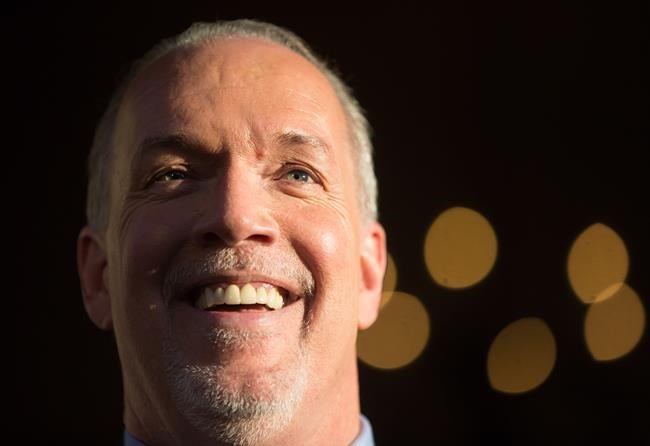

The day after he was tapped to be the next premier of Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω, John Horgan stood on the front lawn of the legislature, doing television interviews, as crews readied the grounds for Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω Day celebrations.

His newfound celebrity meant that he no sooner finished one TV shoot than well-wishers and holiday revellers stepped forward with their own cameras, asking him to pose for photographs with their children.

It was a role that Horgan clearly relished, though he was still getting used to the new title.

“I might be the premier,” he said to one little girl, before catching himself: “I am the premier.”

The 57-year-old NDP leader can be forgiven for feeling a bit disoriented given the tumultuous events of the previous day.

In the span of a few hours, he defeated Premier Christy Clark and the Liberals in a confidence vote in the legislature, met with Lt.-Gov. Judith Guichon at Government House, agreed to form the next minority government with the backing of the Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω Green Party, and emerged as the premier-designate to high-five cheering supporters outside the Rockland mansion.

It would have been a dramatic day for anyone, but it was particularly poignant for a hometown boy like Horgan, who grew up in Saanich, attended Lake Hill Elementary and graduated from Reynolds Secondary.

A big part of who he is and how he plans to lead the province can be traced back to his humble beginnings, he said.

“I’ve had support and help throughout my life, and that’s what motivates me to support other people,” he said. “If you open doors and give people opportunities, extraordinary things can happen.

“So from a personal place, I am the result of all those who have helped me along the way, and I want to pay that forward.”

The youngest of four, Horgan was just 18 months old when his father died from a brain aneurysm, leaving his mother to support the family.

“She didn’t have a driver’s licence,” he said. “She was a stay-at-home mom and she had to become a working mom and learn how to drive and do all of the things that people have to do to participate in the economy.”

It was a rough road at times, and although he has no memories of that time himself, Horgan knows from family members that they received hampers at Christmas and had to rely on the benevolence of friends, neighbours and the church. Despite the challenges, his mom was determined to make sure Horgan had the same opportunities as other boys, he said .

“My mom wanted to get me in whatever she could that was cost-effective,” he said. “Soccer was a good thing because you just had to have the boots, and basketball was a good thing because you just had to have running shoes — and you had to have them, anyway.

“But when I expressed an interest in lacrosse, all of a sudden it got expensive, because you had to buy all this stuff. You had to have pads and a helmet and all these others. That was a big burden for her, but she sacrificed to get me involved in things so my life would be what she characterized as normal.”

Horgan recalls that other people’s dads pitched in by taking him fishing and camping.

“People would step up to help me and that was a great help for my mom,” he said. “She was always grateful and again she instilled in me ‘People have helped us, you should help them.’ That’s just how I’ve rolled ever since I remember.”

He came by his love of sports naturally. His father, Pat, was prominent in the local sports scene before his death.

Horgan still has a cherished sketch of his Dad from the Daily Colonist newspaper in the late 1950s. The tattered clipping, which hangs in his office at the legislature, depicts “an Irishman from County Cork, Pat Horgan,” manager of the Senior A basketball team and “jailer” of the penalty box at lacrosse games.

One of the players in the box sports a Shamrocks sweater and the drawing notes Horgan is well-suited to his job in the sin bin. “He’s an ex-boxer,” it says.

It’s appropriate, then, that sports helped turn a young John Horgan around when it looked like he might go sideways. He credits Jack Lusk, a basketball coach at Reynolds, for seeing something in him that Horgan was unable to recognize at the time.

“He kind of said, ‘You can do way better than you’re doing here, Horgan.’ I was hanging out with the wrong crowd and going down the wrong road, and he brought me back into the mainstream.”

Lusk, 78, and long retired from teaching, said in an interview that it was never a conscious effort on his part to steer Horgan out of trouble. He was unaware, he said, of Horgan’s personal circumstances.

“I was just coaching basketball and if you’re going to play basketball for me, you had to be a solid citizen and he grew into that.”

Horgan ended up playing for Lusk for a number of years.

“He was always an extremely hard-working, nice person,” said Lusk, who is still coaching basketball.

“Typical of John, he’s been very expressive of the thanks he has for whatever I did for him. Obviously, he could have forgotten about me and moved on, but he never has.”

Back on the right path, Horgan attended Trent University for his bachelor of arts degree and Sydney University in Australia for his master’s.

It was at Trent that he met Ellie, on his second day of classes. They’ve been married 33 years and have two grown sons, Evan and Nate.

Horgan told reporters on Thursday night that Ellie was one of the first people he phoned from Government House. She was out, so he left a voicemail, telling her it was the premier calling.

“He’s got a very good home life,” said former NDP MP Lynn Hunter, for whom Horgan worked as a legislative assistant in Ottawa in the late 1980s. “She’s very supportive of him, as are his two boys, and that makes a huge difference if you’re in public life.”

Hunter describes Horgan as her “main go-to guy” in Ottawa.

“He was a saviour, and I remember saying to him at one point: ‘John, you’ve got to run. You’re the full package. You’re good looking, you care about what happens to people and you’re really smart.’ He said: ‘I could never do that. I don’t have a thick enough skin.’ I said: ‘And I do?’

“It’s not a matter of having a thick skin; if you’ve got a thick skin you’re in the wrong business. You should care. So I’m really glad that he took my advice eventually.”

That came later, though. Horgan spent four years in Ottawa before returning to Victoria to work as a civil servant for the NDP governments of the 1990s.

Former premier Mike Harcourt said he gave Horgan a number of critical tasks, including helping to establish the Columbia Basin Trust.

“He understands government, he understands public policy, he understands people and does it naturally,” Harcourt said.

Ex-premier Dan Miller, who made Horgan his chief of staff, describes him as a “regular guy.”

“I think he understands the situation that working people and families are in, and he’s got a lot of experience. He was generally in the group that we used to throw the tough problems at, so he’s very good in terms of finding creative solutions to the problems that beset any government.”

It wasn‚Äôt until 2005, however, that Horgan decided to enter the fray himself. He was at home, he said, ranting about Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω Ferries‚Äô decision to build ships in Germany instead of creating jobs here.

One of his son’s bandmates asked him what he was going to do about it, and, put on the spot, Horgan informed the teenager that he was going to run for office.

He won the riding of Malahat-Juan de Fuca (now Langford-Juan de Fuca) and got re-elected in 2009 and 2013, but took it hard when the party failed to form government under leader Adrian Dix.

Horgan, who finished third in the 2011 leadership race, initially planned to stay out of the 2014 contest to make way for new faces. He changed his mind after younger members of the party encouraged him to run.

He was acclaimed leader in 2014, a fact the Liberals mocked at the time.

“Really? By default?” said then-energy minister Bill Bennett. “It suggests to me that they are completely lost as a political party.”

But Dix pointed out that both Dave Barrett and Harcourt won the party’s leadership by acclamation. “On both those occasions, the acclamation preceded a winning — even a transformative — election for the province and for the NDP,” Dix said at the time. “There’s nothing, of course, guaranteed about history repeating itself, but those are good precedents.”

Three years later, Horgan has managed to end 16 years of Liberal rule and upset a government flush with cash and boasting the strongest economy in Œ⁄—ª¥´√Ω.

He did it, despite efforts by the Liberals to portray him as having an anger-management problem and their supporters referring to him during the campaign as “Hulk Horgan.”

There’s no question he can be defensive when sparring with opposing politicians or the press, but he argues that he’s simply passionate about the issues rather than hot-headed.

Asked about it during the campaign, Ellie told reporters that she’s seen no evidence of it. “Never, ever at home,” she said. “What I will say is he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.”

Hunter said she has never seen Horgan’s temper. “I’m sure he has it, because he does really care,” she said. “I think that makes for a good politician, if you get mad about the right things.”

The problem in Opposition is that the leader can often seem angry about everything, since it’s their duty to oppose the government. It often takes a campaign to show a different side, and former NDP leader Carole James believes Horgan finally got an opportunity to do that in May.

“What I really saw was that the public got a chance to see the John that all of us know,” she said. “Which was a people guy, a person who will be the last one at an event.”

Horgan acknowledges feeling invigorated by the election campaign and the strong response from the public to the NDP platform. But it was the individual stories that stuck with him, meeting a mother and father who lost a daughter to a drug overdose or a woman working three jobs to make ends meet.

“That motivates me and it reminds me of how I was raised,” he said. “That is, if you’ve got an ability to help someone, you should do that.

“That’s why I got involved in government, that’s why I got involved afterward in politics and that’s why I want to lead a government that’s compassionate and focused on making sure people are at the beginning, middle and end of everything that we do.”