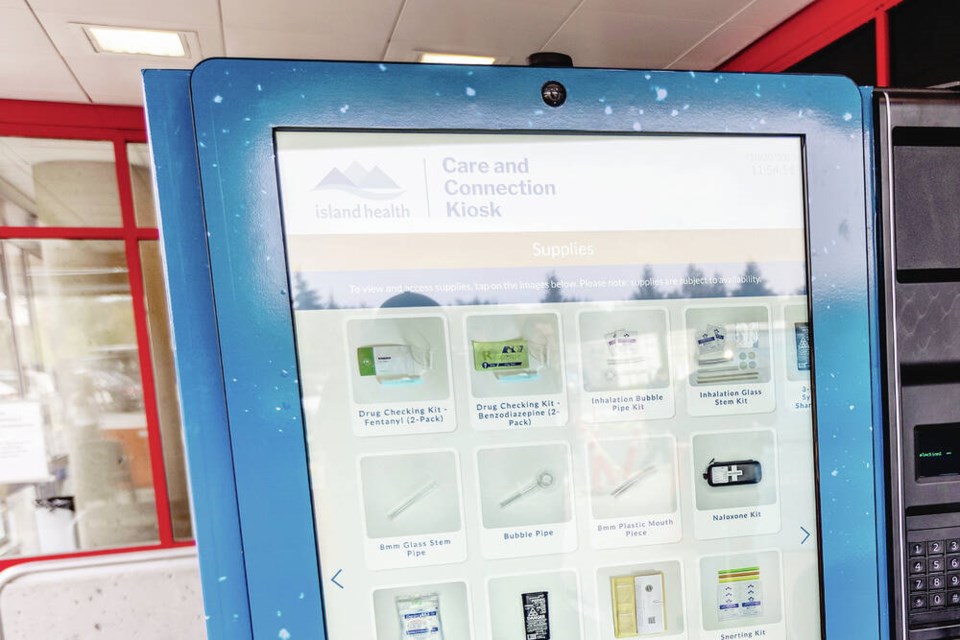

Premier David Eby is asking for a review of vending machines such as those outside Vancouver Island hospitals which dispense condoms, needles, crack pipes, drug-testing strips, wound-care supplies and naloxone kits.

Island Health began installing Care and ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ion kiosks outside the emergency rooms of Victoria General Hospital, North Island Hospital in Campbell River, and Nanaimo Regional General Hospital last fall as part of a pilot project to reduce overdose deaths and infections.

The vending machines, funded by the Mental Health and Addictions Ministry, cost $2,000 a month to lease and are stocked by the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Centre for Disease Control. The three machines have since dispensed 1,100 harm reduction and disease prevention supplies.

Those supplies came under fire Tuesday as enabling drug use instead of offering treatment, after former NDP MLA Gwen O’Mahoney, a Conservative candidate in Nanaimo-Lantzville, posted a video of the kiosk outside Nanaimo’s hospital. She has family members who have battled addiction.

“Let’s go get a free crack pipe and cocaine-[snorting] kit,” she says in the video, hitting the touch screen and watching the items dispensed. O’Mahoney then reads the information video “so now we can learn how to snort cocaine.”

She maintains the vending machines could trigger people to use drugs or normalize drug use.

The Fraser Health Authority came under fire for offering free home delivery of drug injection and inhalation supplies.

Eby said the machines were meant to dispense wound care, naloxone and drug testing strips — items “we’re hoping that people will use to reverse and prevent overdoses.”

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside is being asked to oversee a review of distribution of drug harm-reduction supplies “that don’t involve direct contact between a service provider and somebody struggling with addiction,” Eby said at an unrelated press conference.

“We want to make sure that people are in contact with the system, that they’re talking to a doctor or a nurse or a social worker or somebody to get them connected into the system, and we also want to keep as many people alive as possible.”

When Island Health introduced the machines last fall, however, it was partly based on the idea the machines would serve people who wouldn’t or couldn’t seek in-person services.

The kiosks are intended to be accessible for people who don’t get off work until the evening or want anonymity, the health authority said in a statement on Tuesday.

“The goal is to address gaps in service for people, who may not want to be associated with harm reduction services, such as people working trades, due to stigma or fear of repercussion.”

The health authority said in addition to providing around-the-clock free access to harm-reduction supplies, the machines also provide information and contacts for substance use services, mental health supports and community resources.

Island Health said each kiosk is maintained and restocked by a peer support or addiction and recovery worker, at the hospital full-time

Island Health medical health officer Dr. Charmaine Enns, told the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ in October the touch-screen-operated kiosks act as an extension of the ER.

The kiosks provide wound-care and sexual health supplies that people “have a right to access” but cannot get to for various reasons, she said.

Enns said she hoped the kiosks would be one more way to keep people alive and connect them with help.

There are no drugs or medications in the machines apart from opioid-overdose-reversing naloxone.

Unregulated toxic drugs are the leading cause of death in British Columbia for persons aged 10 to 59, accounting for more deaths than homicides, suicides, accidents and natural diseases combined, according to the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Coroners Service.

About 15,000 people have died of the toxic drug supply since it was declared a public health emergency in 2016.

It is males using drugs alone at home who are most often dying from toxic-drug poisonings. Of those who died in 2023, 70 per cent were age 30 to 59, and 78 per cent were male.

Eby said the effort to keep people alive and connected to the health care system so that they will seek recovery and treatment is a “delicate balance.”

“We want to make sure we’re getting it right in a way that ensures community safety and confidence in these approaches,” he said, expressing gratitude for the people on the front lines with those struggling with addiction. “It’s a hard job, and they, like us, we all want to keep people alive, get them into treatment,” said Eby. “But the core of it is that they need to be in contact with a person and so we’ll do all we can to find that balance of maximizing that possibility for contact while keeping people alive.”

The kiosk at Victoria General Hospital was removed in mid-December due to challenges with the location related to constrained space and fire alarm activity.

People can still access harm reduction supplies from the emergency department staff at Victoria General.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]