Replacing current production from open-net salmon farms in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ with land-based systems would require at least $1.8 billion in investment, government subsidies and regulatory changes.

That’s the conclusion of a new on land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) commissioned by the ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ government.

The analysis was conducted by Counterpoint Consulting, and was in response to the federal government’s policy to “transition” ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s salmon farming industry.

“Farming Atlantic salmon and steelhead profitably using RAS presents many challenges,” the analysis concludes. “Regulatory uncertainty, high capital cost, low returns on investment, and lack of incentives to locate in British Columbia remain the primary constraints challenging the development of RAS salmon farming in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½”

“We have concluded from our research and analysis that RAS development in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is possible, but at smaller scales and not in isolation from the larger aquaculture sector currently operating in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½"

In 2020, the federal minister of Fisheries and Oceans was mandated by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau “to create a responsible plan to transition from open net-pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters by 2025.”

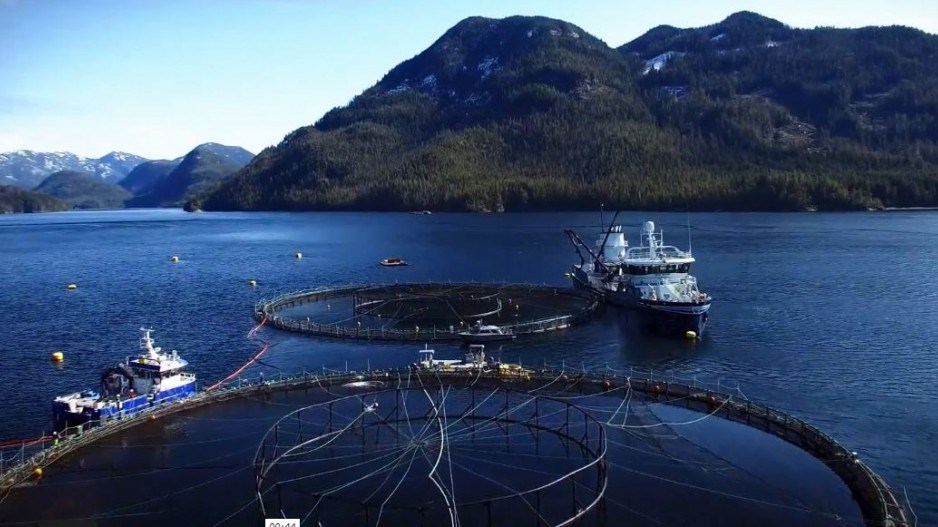

The transition was ordered to address concerns that open-net salmon farms pose a risk to wild salmon, mainly through the transmission of disease and sea lice.

About one-quarter of the open-net salmon farms in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ have already been shut down -- mostly in the Discovery Islands -- as part of that transition plan.

It has been assumed that the “transition” the federal government has in mind means moving all salmon farms in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ out of the water and onto land.

In recent consultations with stakeholders, Fisheries and Oceans Minister Joyce Murray appears to have modified that position to “progressively minimize or eliminate the interactions between farmed and wild salmon.”

That could open the door to hybrid systems that attempt to minimize interactions between wild and farmed salmon to reduce the chance of disease and sea lice transmission – something environmentalists and many First Nations oppose.

In 2020, DFO produced a study that found RAS systems were “commercially ready.” The Counterpoint Consulting analysis likewise finds that RAS systems are feasible – they’re just very expensive and risky investments.

“The complexity of RAS facilities makes them very risky investments,” the analysis says. “While a limited number of RAS projects have successfully grown market-size salmon, long term profitability remains elusive.”

Replacing the current volume of salmon produced in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ through open-net salmon farms – about 90,000 tonnes -- with RAS production would require $1.8 billion in investments, the analysis estimates.

Salmon farms in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ already use RAS technology to rear salmon to the smolt stage before they are moved to open-net pens. Some are working on hybrid approaches that would allow salmon to spend longer in RAS systems before being moved to the ocean.

“This report released by the province supports what salmon farmers have been saying for many years,” said Brian Kingzett, executive director for the BC Salmon Farmers Association.

“Our sector strongly supports RAS technology – in fact we are experts at using RAS to grow salmon -- but to move the entire sector on land isn’t a realistic option, nor is it required to protect wild salmon.”

The Counterpoint report notes that most RAS systems in the world are still largely in the planning or development stage.

“The difficulty in assessing the many projects noted in the trade press is access to performance data, which is not readily available.”

Two systems that are in operation are the large Atlantic Sapphire project in Florida and the smaller Kuttera system in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ Both appear to be falling short of the hoped-for production levels, the Counterpoint report estimates.

“For example, Kuterra was designed to produce 470 tonnes at steady state but never achieved even 35% of that production target, nor did it achieve target harvest weights. Similar conclusions can be drawn from public reporting of Atlantic Sapphire’s performance, with harvests reaching 10 per cent to 40 per cent of targets in their first three years of production.”

One barrier to the development of RAS systems in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is the regulatory framework, the study notes.

“Aquaculture regulation in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is complex and inconsistent. This is particularly a problem in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ where federal, provincial, local (Regional Districts), and First Nations’ laws, by-laws, and regulations may be applied to licensing and permitting aquaculture projects.

“During our research we heard from proponents who described delays of two years or more in permitting as their number one concern when making decisions about developing RAS salmon farming projects in BC.

“The publication of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s first-ever Aquaculture Act, currently under development, might improve this situation, but regulatory uncertainty remains a key challenge to the development of RAS salmon farming in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½”

The report recommends that RAS licensing be deregulated “where there is no impact on fish or fish habitat.” It also recommends that the government develop an inventory of potential sites in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ for land-based farms, "including an assessment of infrastructure, well water profiles, wastewater discharge profiles, and accessible hydro power.

"Regulatory changes critical for the future development of RAS farms will take several years to put in place," the analysis says. "Thereafter, it will take additional time for the development and construction of projects. Yet more time will pass before the first fish are harvested and only then would a farm be on the path towards steady state operations.

"We estimate that it will be at least ten years before a significant RAS production sector is operating at steady state in British Columbia."