ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s federal government moved to create its own definition of “forest degradation” days after the European Union passed a law restricting the import of products linked to the practice.

The new EU law will require wood products imported from Canadian forests — as well as anywhere else in the world — to be marked with geographic coordinates showing where they were harvested. Companies will then be required to combine that with satellite data and show their operations did not contribute to deforestation or forest degradation from 2021 onward.

Last year, those measures prompted ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s ambassador to the EU to lobby lawmakers into adjusting the bill to exclude requirements around forest degradation. But those efforts failed, and in December, the law passed. Once the rules are in force — likely sometime in June 2023 — big companies will have 18 months to get into line.

ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s lobbying record, as well as its quick pivot to redefine forest degradation, has worried some environmental groups, who say a new definition could function as a loophole to sell the country’s wood products to the EU and any other jurisdiction that follows in its foot steps.

“It certainly raises eyebrows that this is coming so closely on the heels of the EU law when ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is finally being held accountable for the impacts of its logging practices,” said Jennifer Skene, the natural climate solutions policy manager for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

Skene said ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ has “clung to a narrative” that its forestry sector is sustainable and in line with its climate and biodiversity targets. She said the EU law challenges that idea.

“This is the first major threat to that long-standing myth,” Skene said.

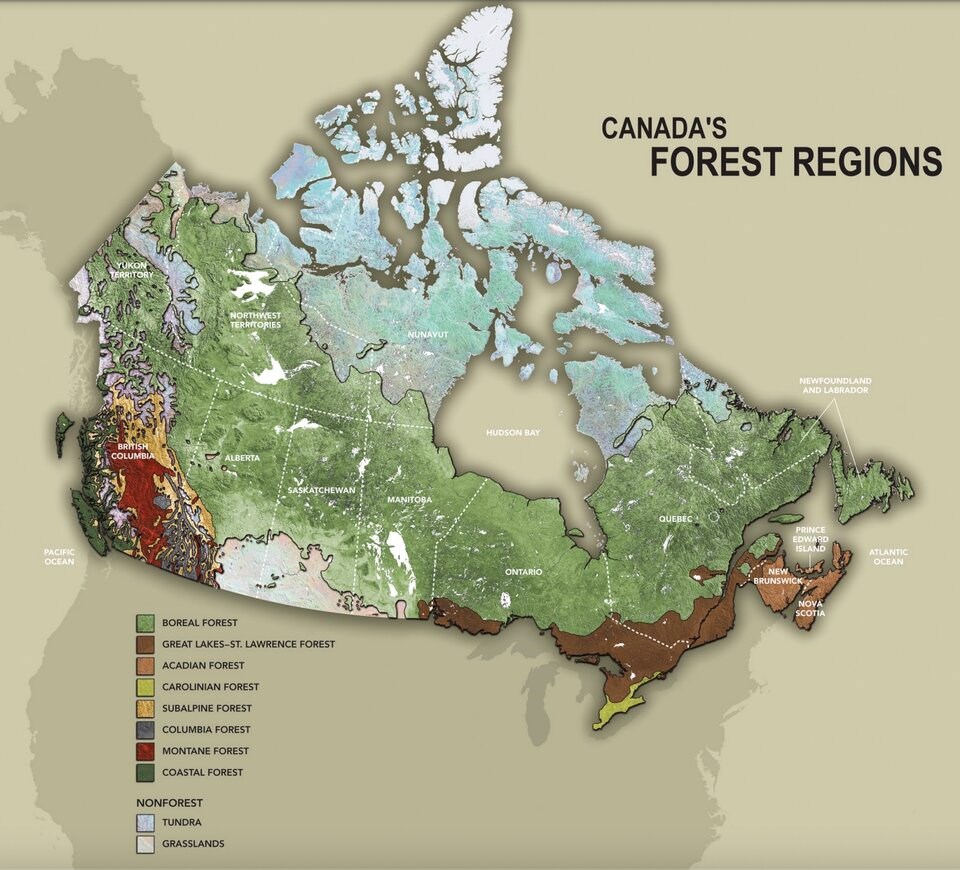

​Home to almost 10 per cent of the planet's forests, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is the largest net exporter of wood products in the world. But over the last two decades, the country has lost more than 19.6 million hectares of primary forest, the third highest rate of intact forest loss in the world after Brazil and Russia, according to Global Forest Watch.

Much of that is due to wildfire or beetle infestations. But in many provinces, logging, oil and gas exploration, and other human pressures have degraded forests so much that they no longer provide the habitat many animals need to survive.

“The way that we're doing logging in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ right now is leading to species decline, which obviously, in and of itself means that it's not sustainable,” said Rachel Plotkin, the boreal forest manager for the David Suzuki Foundation.

“It's changing the natural composition of forests.”

A murky definition

Since the end of the last ice age, a third of the have disappeared. Much of that loss has been driven by deforestation — when humans raze a forest to make way for some other use. Clearing trees to put up a parking lot or golf course counts. So does a landowner cutting down a forest to build a housing development.

Today, deforestation tends to be concentrated in sub-tropical forests and remains largely driven by expanding agriculture. From space and on the ground, it's relatively easy to measure how much Indonesian and Brazilian jungle is razed to make way for vast swathes of farmland.

“Forest degradation,” on the other hand, captures a spectrum of human disturbances — from industrial-scale logging to oil and gas operations.

As long as trees are replanted, clear-cutting primary forests doesn't count as deforestation. But most international bodies agree that it could lead to forest degradation.

In ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, logging companies are required to replant trees after a forest is cut. The “sustained yield” model, as it’s known, has long framed Canadian forestry as an endlessly renewable resource. But that logic has been increasingly questioned in recent years as many species that rely on the forest are pushed closer to extinction.

Earlier this year, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s environment minister said he would issue an emergency order to protect 2,500 hectares of old-growth forest in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s Fraser Canyon. Logging operations, an analysis found, posed an imminent threat to the habitat of .

Another recent analysis found more than half of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s most threatened despite government promises to protect them.

Vast networks of logging roads combined with fossil fuel operations have carved up forest habitat into fragments. That has helped push endangered caribou populations — an umbrella species whose health mirrors the wider ecosystem — closer to extinction across seven provinces, said Plotkin, who has spent years tracking the health of boreal forest ecosystems.

“If you're driving wildlife decline, then you can't possibly say that you're truly sustainable,” she said. “That's a huge litmus test.”

The sustainability claims of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s forestry sector faces credibility tests on multiple fronts. In January, ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s Competition Bureau launched an investigation into the country's largest forest certification program, the , over claims it failed to live up to its sustainable claims and engaged in false advertising.

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) — another more rigorous forest certification program — has shrunk its footprint in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ in recent years. Since 2020, roughly 5.5 million hectares of forests in Ontario and Quebec have lost sustainability certifications after FSC ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ found three logging companies had degraded them so much that caribou populations were beyond the point of no return.

FSC ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s François Dufresne called the EU law restricting unsustainable forestry products a “wake-up call” for ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ that could pose a risk to its forestry exports.

“We've lost ground recently,” he said.

The Forest Products Association of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, an industry group representing wood product producers, said it was not available for comment.

Deforestation vastly undercounted in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, suggests study

In some cases, the line between deforestation and forest degradation has become increasingly blurred.

Since 2019, researchers at have released a series of reports investigating 300 historical cut blocks across Ontario. In many of the disturbed areas, where soil had been torn up or compressed to build roads or landings, they found trees never grew back decades after logging had ended.

The net effect, according to the group, is that logging operations have led to 21,700 hectares of deforestation in Ontario alone. That’s about seven times more deforestation than the government of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ reports for the entire country every year, according to the authors.

“You can see the same legacy across the country,” said Janet Sumner, the group's executive director. “There’s de-facto deforestation going on as a legacy of tree farming.”

As deforestation goes uncounted in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, Sumner says cutting ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s ancient trees and calling it “forest degradation” misses the point.

“If it were sustainable, you wouldn’t be running out of old growth,” Sumner said. “I don’t know how you can claim that will come back on any realistic timescale.”

“Right now, we’re hiding behind a definition.”

Process to launch domestic definition ramped up two days after EU law passed

Two days after the EU passed its December 2022 law restricting the import of products linked to deforestation and forest degradation, emails seen by Glacier Media show the assistant deputy minister of Natural Resources ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ sent an invitation to nine environmental groups asking them to “exchange views” on how to define forest degradation.

Nature ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s Michael Polanyi, who attended two meetings since then, said the conversations raised concerns economic interests might be used to water down a scientific definition of forest degradation.

“Don't try and come up with a definition that says, 'Well, there's no net forest degradation taking place because the economic benefits, the job benefits outweigh the harm being done to biodiversity,'” Polanyi said.

A letter sent to the co-chairs of the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers’ Definitions Task Team, warned the process to define forest degradation was moving too fast, and included too few Indigenous groups and representatives from Environment and Climate Change ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

Using terms like “sustainable forest management” to define forest degradation “blurs the lines between science and policy,” warned the letter, which was signed by Polanyi and representatives from seven other environmental groups.

Other environmental groups who took part in the government talks declined to sign the letter. Some said they were hopeful a new definition of forest degradation could overhaul the most destructive elements the Canadian logging sector.

“It's pivotal,” said Plotkin. “It could be the card that forces our hand in taking an honest look at our current logging practices and making the significant and systemic changes that are needed.”

In May, the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers (CCFM) held “constructive discussions on elements of a definition” of forest degradation, said Barre Campbell, Natural Resources ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ spokesperson. So far, Campbell said CCFM has spoken to industry, environmental groups, academics, and certification bodies on what the definition should mean.

Shortly after, signs emerged not everyone involved in that process was happy with the way it was going. The David Suzuki Foundation released an criticizing the CCFM of upholding the status quo and “perpetuating the myth that Canadian forestry practices are already sustainable.”

“If that were true, boreal woodland caribou wouldn’t be threatened with extinction throughout ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½,” said the group.

ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s pattern of overseas forestry lobbying

Skene said she worries that creating a domestic definition of forest degradation will follow in the footsteps of a wider international lobbying effort by ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½.

In the lead up to the signing of the EU law, Canadian ambassador to the EU Ailish Campbell sent a letter to members of the European parliament saying proposed regulations would add “burdensome traceability requirements” and risk $1 billion in forestry and agricultural exports.

Letters seen by Glacier Media also show several politicians lobbying senators in New York and California to remove the word “boreal” from proposed bills initially written to limit the import of wood products linked to deforestation or forest degradation.

In both cases, the lobbying appears to have been successful. California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the California bill, but not before ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ had succeeded in getting it amended. And in New York, the bill is now passing through that state’s legislative process without reference to “boreal” forests.

But the EU law passed without the amendments ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ was looking for. Skene said the law is specific enough that ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ is getting “increasingly boxed in to the science.”

To date, Canadian forestry exports have not been affected by the EU law, but that could change in the coming months as the continent moves to enact it, according to a senior official with Canadian Forest Service, who spoke to Glacier Media on background.

ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ among a world looking to define forest degradation

In 2021, 144 leaders from around the world signed the , and in so doing, agreed to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. That agreement was further bolstered when last fall, more than 100 countries committed to protect 30 per cent of their land base by 2030.

The problem, said James Snider, WWF-ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s vice-president of science, knowledge and innovation, is that without a clear definition of forest degradation, it becomes impossible to measure progress or failure.

“This question of degradation has been looming large on the horizon for the forest industry here for quite some time,” Snider said.

A holistic definition of forest degradation must include the composition of species, the age of the forest and how well animals can move through it before running into a cut block, said Snider.

Then scientists and policymakers need to agree on some basic limits: where does a forest begin and end? Over how many years should you measure degradation? And what ecosystem services should get counted?

Finally, said Snider, you have to figure out how to effectively measure every indicator on a regular basis across a country the size of ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½, which currently has more than .

“It’s complicated,” Snider said. “[But] we don't have seven years to argue about what the definition is.”

The federal government says it is working to merge those forest types into a national classification system.

For Sumner, better data is the linchpin that will allow Canadians to understand the state of their forests. That, she said, will require both hard work by scientists in the field and a commitment to better satellite technology.

Currently, satellite imaging usually measures forest cover in 40-metre pixels — like “looking through Coke-bottle lenses,” as Sumner puts it.

Getting that resolution down to under five metres — and then using artificial intelligence to process all that information — would shine a spotlight on ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s forests and offer hard numbers that would be hard to refute.

“We need to start measuring if we want to know the state of Canadian forests,” Sumner said.

No European response

It’s not clear how EU officials are receiving ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½’s move to create its own definition of forest degradation.

Environmental groups have sent letters to , Director-General of the Environment Department of the European Commission, expressing their concern. But Fink-Hooijer’s office turned down Glacier Media’s request for an interview.

In May, Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson told the Fredericton Chamber of Commerce that the EU law was pushing provinces to confront forest degradation in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½. Adapting to the new law could require “monitoring and verifying, and changing practices” to ensure markets aren’t closed to ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s forestry exports, he said.

​In an interview with Glacier Media, Wilkinson added the push to define forest degradation in ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ was about “doing the right thing from an environmental perspective as we continue to manage our forests.”

The minister also described the move as “a defensive measure for ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½ to be able to have a good engagement with the European Union” and to show the continent's leaders ÎÚÑ»´«Ã½'s “good forestry practices” and how it intends to improve them.

Nearly 178,000 jobs and $42 billion in annual forestry exports are at stake. But those immense economic benefits are increasingly getting weighed against two other unwavering realities — in a global rush to head off an extinction crisis and the gathering effects of climate change, healthy forests will be essential.

“We're asking that big societal question,” Snider said. “Is it possible to do all three of those things at the same time?”